‘Tis the season of the Japanese New Year’s trinity: osechi, oseibo and nengajo. Like newsy Christmas cards, the nengajo is a recap of family or personal news mailed in postcards during the weeks preceding the end of the year and efficiently delivered all over Japan promptly on January 1.

The winter gift-giving season is in full swing, with companies and individuals sending oseibo gifts as thank-you expressions for kindnesses over the year. Most gifts are food or household items like cooking oil or soap.

The best of the traditions is osechi ryori, traditional New Year’s cuisine. Osechi is not something one can find in a restaurant because it’s eaten only one time a year, at home or when visiting others at home. The first days of the new year are for resting and rejuvenating, including for those responsible for providing meals, traditionally women. All stores and most restaurants are closed. Food is prepared ahead of time with materials that can be preserved, to be eaten over several days beginning on New Year’s Day.

Osechi ryori is most often served in jubako lacquer boxes with small compartments for each dish. The boxes are stacked one on top of the other in a tower of plenty. Traditionally, families owned a jubako that would be stuffed each year using recipes handed down through generations. Many modern households prefer to order premade osechi from restaurants and depachika food halls in department store basements. Recently, famous restaurants and celebrity chefs have begun to offer elaborate creations with less traditional foods. A typical jubako for four people will cost an average of $300; however, it would not be difficult to spend close to $1,000. They must be ordered weeks in advance from catalogs filled with enticing photographs or plastic models in stores, and they sell out quickly.

Osechi ryori is most often served in jubako lacquer boxes with small compartments for each dish. The boxes are stacked one on top of the other in a tower of plenty. Traditionally, families owned a jubako that would be stuffed each year using recipes handed down through generations. Many modern households prefer to order premade osechi from restaurants and depachika food halls in department store basements. Recently, famous restaurants and celebrity chefs have begun to offer elaborate creations with less traditional foods. A typical jubako for four people will cost an average of $300; however, it would not be difficult to spend close to $1,000. They must be ordered weeks in advance from catalogs filled with enticing photographs or plastic models in stores, and they sell out quickly.

Because of the expense, many households will create their own from foods bought in the store. Tsukiji Market is flooded with people buying osechi foods, and supermarkets clear their shelves of the usual foodstuffs and stock many varieties of special seasonal fare. [Editor’s note: The inner wholesale market at Tsukiji closed on October 6, 2018.]

Osechi foods range from sweet to salty and each has significance. The general nature is good fortune, prosperity and health. When tucked into the jubako they begin to represent a gorgeous Japanese garden.

The main elements of osechi ryori and their significance are varied. Shiny kuromame black beans are a perfect symbol of osechi and are said to bring good health. Kazunoko herring roe is another staple of osechi and signifies abundance. Kazu means “number” and noko means “child;” thus kazunoko is also a wish for expanding the family in the coming year. Families are quite particular about the quality and appearance of the pale-yellow, salty kazunoko they serve. Just as important is the tazukuri, dried anchovies glazed with sweet mirin, sugar and soy sauce, signifying a bountiful rice crop because the Japanese name sounds similar to that for planting rice. The small fish were at one time so abundant in Japanese waters that they were used for fertilizing rice fields.

The traditional colors of New Year’s are red (to fight against evil) and white (purity). Kamaboko pressed fish-cake slices are semicircular with a white inside and pink outer lining, symbolizing the first sunrise of the year. Namasu pickled carrots and daikon radish are another red-and-white combination and a good omen.

Bringing back the sweetness factor is kurikinton, a puree of chestnuts and sweet potatoes, for good economic fortune. Buddhist philosophy gets a nod in vinegared lotus root tsubasu. The lotus root holes symbolize an unobstructed view of the future. At our house we all try to look unobtrusive as we slyly snag an additional plump and costly ebi shrimp in its shell, its long, curved antennae twirling out from its head. Because shrimp molt their shells they are thought of as a symbol of life’s renewal and are also a representation of long life because their curved back resembles an elderly person.

Bringing back the sweetness factor is kurikinton, a puree of chestnuts and sweet potatoes, for good economic fortune. Buddhist philosophy gets a nod in vinegared lotus root tsubasu. The lotus root holes symbolize an unobstructed view of the future. At our house we all try to look unobtrusive as we slyly snag an additional plump and costly ebi shrimp in its shell, its long, curved antennae twirling out from its head. Because shrimp molt their shells they are thought of as a symbol of life’s renewal and are also a representation of long life because their curved back resembles an elderly person.

Osechi ryori is usually eaten with iwaibashi, wooden chopsticks that have been placed in a wrapper decorated with the character for kotobuki (longevity and prosperity) or another image, usually the appropriate animal on the Chinese calendar in the coming year. Both ends of the chopsticks are thin, and the meaning behind this is that both god and people can eat at the same time – one end for the god and the other for humans.

Possibly one of the highlights of waking up on the first day of the year is having otoso, New Year’s sake. Unlike sake for the gods, it is not refined sake but sake infused with Chinese herbs for health. In pouring, the order is supposed to be from young to old.

Osechi ryori is a long, rambling meal, as everyone picks and chooses their favorite items from the jubako. The savory finale is ozoni, a bowl of dashi broth with dense mochi rice cakes softening as they float to the top along with vegetables, chicken or fish.

Osechi ryori also includes dessert. Our favorite is creamy hoshigaki, dried persimmon, its sweet essence seeming to reach all the way to the sinuses. Probably most popular is the mound of bright orange mikan mandarins that inevitably appears at the end of winter meals.

The osechi meal is a luxurious treat that is enjoyed numerous times over several days – and just enough so that nobody complains that it’s only once a year.

Editor’s note: Happy New Year! To celebrate the start of 2019, we thought it was worthwhile to rerun this article on osechi ryori, traditional New Year’s cuisine in Japan, which was originally published on January 1, 2016.

July 25, 2018 The Cherry On Top

July 25, 2018 The Cherry On Top

An employee at Sirvent tops the shop’s artisanal ice cream with bright red candied […] Posted in Barcelona June 27, 2022 Lisbon’s Post-Colonial Feast

June 27, 2022 Lisbon’s Post-Colonial Feast

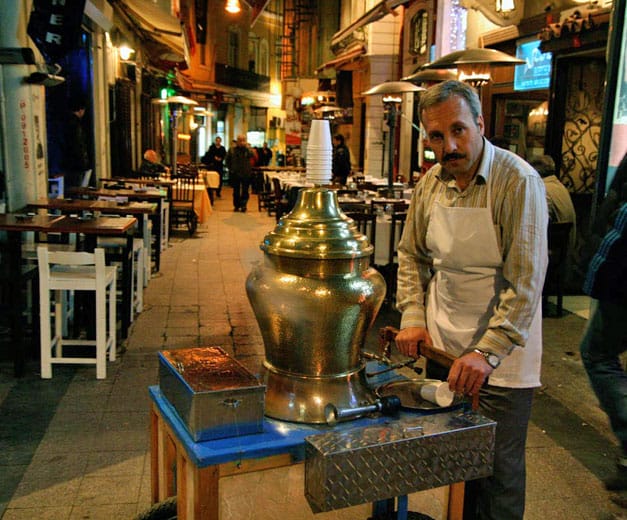

Quick Bite: On this full-day tour of central Lisbon, we’ll study the cuisines, history […] Posted in Lisbon December 3, 2013 Salep

December 3, 2013 Salep

When we last visited Cemal Bey, he was sitting behind a desk in a small, bare office on […] Posted in Istanbul

Published on January 01, 2019

Related stories

July 25, 2018

BarcelonaAn employee at Sirvent tops the shop’s artisanal ice cream with bright red candied cherries. Sirvent is one of Barcelona’s turronerías (also called torronerías), so-called because they dedicate themselves to making artisanal nougat (turrón) in the winter. But come summer, many flock to them for a cooling ice cream or horchata.

June 27, 2022

LisbonQuick Bite: On this full-day tour of central Lisbon, we’ll study the cuisines, history and diversity of Portugal’s former colonies. Get a taste of Cape Verdean cachupa, Brazilian pastries, Goan samosa, layered convent cake bedecked with spices and Angolan piripiri sauce and meet the people in the kitchen keeping the traditions of these communities alive.…

December 3, 2013

IstanbulWhen we last visited Cemal Bey, he was sitting behind a desk in a small, bare office on the second floor of a decrepit building near the Egyptian Bazaar in the city’s old quarter (he has since moved). Three large burlap sacks filled with what look like jumbo-sized yellow raisins are all that adorn the…