Update: This spot is sadly no longer open.

André Magalhães is not your usual well-known, successful chef. For starters, he doesn’t even look like a chef, as he never wears whites and a hat, but rather an apron and a beret. Also, he has seen more than most of his Portuguese peers, having traveled through Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean working in kitchens, after finishing high school in the United States in the early 1980s.

Instead of chef, many call him taberneiro – the owner of a taberna, a small, unpretentious spot to drink wine. That’s because of his most successful venture in Lisbon: Taberna da Rua das Flores, a small restaurant he opened in 2012 where he serves a mix of original and traditional recipes, either faithfully recreated or creatively remixed in small portions, using seasonal ingredients from local producers. Since the restaurant doesn’t take reservations, getting a table there is no easy task, especially during the high season, but it is always worth the wait.

Outside of kitchen, André is a gastronomic bookman who likes to travel, study and understand why we eat what we eat. “Part of what I like to do the most is to find the footprints of Portuguese food all around the world,” he says. That’s why the idea of doing something with Macanese food had been on his mind for a while. “Macau’s cuisine was probably the first example of a true fusion cuisine in the world,” André recalls, turning the conversation into an impromptu history lesson. “When the Portuguese settled in Macau, during the 16th century, they not only brought people from other colonies but also married into local families.”

Outside of kitchen, André is a gastronomic bookman who likes to travel, study and understand why we eat what we eat. “Part of what I like to do the most is to find the footprints of Portuguese food all around the world,” he says. That’s why the idea of doing something with Macanese food had been on his mind for a while. “Macau’s cuisine was probably the first example of a true fusion cuisine in the world,” André recalls, turning the conversation into an impromptu history lesson. “When the Portuguese settled in Macau, during the 16th century, they not only brought people from other colonies but also married into local families.”

In those days, Macau was the epicenter of all Portuguese-related activities in Asia, with people and products from all over the continent coming and going. Since both locals and newcomers had to eat, it is easy to picture new recipes being brought to life every day.

Over 450 years later, those recipes are mainly still a mystery for most Portuguese people. Even though Macau was Portugal’s last colony, having been reverted to China in 1999, Macanese eateries have been practically nonexistent in Lisbon, an obvious contrast to what happened with the other former outlying territories, from Brazil to Goa: all, except for East Timor, are very well represented in the city’s restaurant sector. Casa de Macau, a cultural association dedicated to celebrating that long-lasting relationship, used to host a weekly lunch of Macanese food on Wednesdays. But they stopped doing it sometime last year and have no current plans to resume activity.

Even though Macau was Portugal’s last colony, Macanese eateries have been practically nonexistent in Lisbon.

Enter Taberna Macau. That’s the name André gave to the food stall he opened last December at Mercado Oriental, a food court located on the top of a Chinese supermarket in Martim Moniz, Lisbon’s most multiethnic neighborhood. “Being a long-time client of the supermarket I already knew Joana, the manager. When she told me she wanted to open a food court I told her that we should, instead, create an hawker center, like the ones in Singapore, and have different stalls serving different foods from different Asian countries,” he explains. And that’s what happened.

André runs three of those stalls: Taberna Macau, Bao Bar (he went to Taiwan to learn the recipes of Lan Jia, probably the greatest gua bao – traditional steamed buns usually stuffed with pork belly – restaurant in Taipei) and Kamakura, a Japanese sandwich shop. “Katsu sando [a Japanese breaded and deep-fried pork cutlet sandwich] is already a food trend around the world,” the chef says, explaining the inspiration behind Kamakura. “And it also has something to do with the Portuguese heritage, since Portuguese missionaries in the 1600s were the ones that introduced fried food in Japan.”

But we’re more interested in Taberna Macau. The recipes André chose to put on the short menu are the staples of that fusion cuisine born sometime during the 16th century. Sopa de lacassá (€7), for instance, is a spicy rice-noodle and prawn soup, which, according to André, is “Macau’s most famous soup, their own caldo verde.” Bao zai fan (€8) is a clay pot sausage rice that resembles those rice dishes that are popular in northern Portugal and usually served with cabrito assado, or roasted baby goat.

Maybe the perfect example of the aforementioned fusion is chatchini de bacalhau (€9), which involves the good old Portuguese favorite codfish, but with an obvious Asian twist – the use of turmeric and coconut milk. And there is even a Macanese version of cabidela (€9) in which the rice – usually cooked in chicken’s blood, with water and vinegar – is replaced by potatoes and the chicken by duck. The blood-infused sauce also tastes different: much sweeter and softer than the Portuguese cabidela. “That happens because this Macanese version uses cinnamon and star anise,” the chef reveals.

All in all, it looks like we have been missing a lot of the good stuff for way too long: it’s nice to finally eat you, Macau.

January 4, 2022 In Love Again

January 4, 2022 In Love Again

It was a late night in 2009 when Thanos Prunarus finished his shift at Pop, a […] Posted in Athens June 23, 2014 Ratafía

June 23, 2014 Ratafía

In Catalonia around the summer solstice, we make one of our most traditional liqueurs, […] Posted in Barcelona December 3, 2013 Salep

December 3, 2013 Salep

When we last visited Cemal Bey, he was sitting behind a desk in a small, bare office on […] Posted in Istanbul

Published on February 13, 2019

Related stories

January 4, 2022

AthensIt was a late night in 2009 when Thanos Prunarus finished his shift at Pop, a now-shuttered bar in Athens’ historical center on the tiny Klitiou pedestrian street. He was just a few steps out the door when he spotted a “For Rent” sign taped to the front of an old, empty store. This area…

June 23, 2014

BarcelonaIn Catalonia around the summer solstice, we make one of our most traditional liqueurs, ratafía, for which the herbs, fruit and flowers that are macerated in alcohol must be collected on Saint John’s Eve, or June 23. This highly aromatic digestif has long been believed to have medicinal properties. There’s even an old Catalan rhyme…

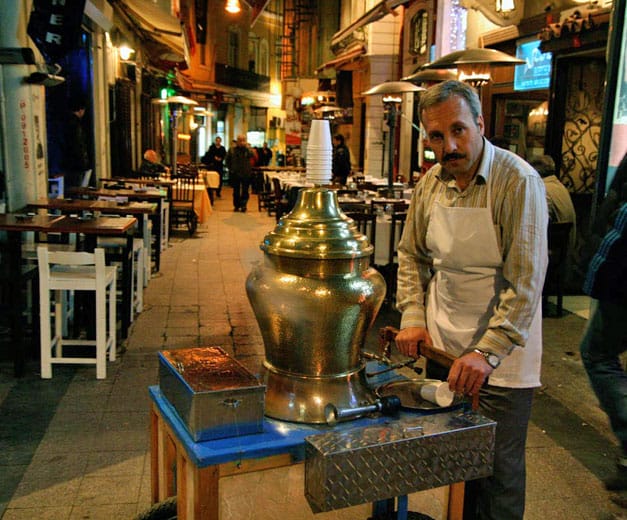

December 3, 2013

IstanbulWhen we last visited Cemal Bey, he was sitting behind a desk in a small, bare office on the second floor of a decrepit building near the Egyptian Bazaar in the city’s old quarter (he has since moved). Three large burlap sacks filled with what look like jumbo-sized yellow raisins are all that adorn the…