Enslaved Africans first stepped onto North American soil in 1619, unloaded by the Dutch West Indian Company in Jamestown, Virginia. Colonists first auctioned enslaved Africans in New Amsterdam (now New York City), New York, in 1626. According to the New York Historical Society, during the colonial period, 41 percent of the city’s households had enslaved peoples, compared to 6 percent in Philadelphia and 2 percent in Boston. Only Charleston, South Carolina, rivaled New York in the degree to which slavery entered everyday life. By 1756, enslaved Africans made up about 25 percent of the populations of Kings, Queens, Richmond, New York and Westchester counties, says historian Douglas Harper.

Because of a longer and colder winter, the lives of Queens County and Long Island slaves differed from those of their southern counterparts. Smaller numbers of enslaved with more skills predominated, including agricultural, and chances to escape were few since they were more closely watched. Though slavery was abolished in 1863, Jim Crow laws kept society segregated and unequal.

In the United States, the advent of the automobile conjured a world with open roads to journey with wonder, spontaneity, and freedom. Yet this romantic whim did not apply to all. Enter Victor H. Green. A postal worker from Harlem, Green published The Negro Motorist Green Book for Harlem, his city, and New York in 1936. By 1949, The Green Book provided African-American travelers a guide to hotels, restaurants, taverns, road houses, gas stations, and homes where they could be sure to have a place to eat and rest, as the sun began to set, without the threat of violence. Green continued, and published the series for nearly 30 years, until President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the Civil Rights Bill into law in 1964 ending the legal practice of segregation.

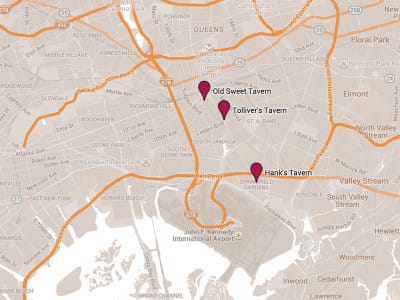

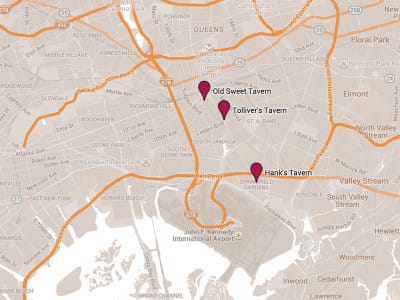

From the mid-50s onwards, Green added many more establishments that catered to the African-American traveler as the Civil Rights movement gained momentum. But in the early 50s, Queens had its own versions of Jim Crow, and a limited number of safe stopovers in segregated America. Queens boasted only seven Green Book establishments. These places were in parts of Queens that had large African-American populations, like Flushing, Corona and Jamaica. Jamaica, with St Alban’s, Addisleigh Park and Hollis, grew to be major centers for African-Americans of all types – poor, middle- and upper-class – in search of better homes beyond Harlem and Brooklyn.

From the mid-50s onwards, Green added many more establishments that catered to the African-American traveler as the Civil Rights movement gained momentum. But in the early 50s, Queens had its own versions of Jim Crow, and a limited number of safe stopovers in segregated America. Queens boasted only seven Green Book establishments. These places were in parts of Queens that had large African-American populations, like Flushing, Corona and Jamaica. Jamaica, with St Alban’s, Addisleigh Park and Hollis, grew to be major centers for African-Americans of all types – poor, middle- and upper-class – in search of better homes beyond Harlem and Brooklyn.

Thomas Tolliver, a native of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, transferred his skills as a night club owner in the South to Jamaica when he opened Tolliver’s Crystal Casino on New York Boulevard in 1944 with his wife Jennie Phillips. M. Feurtado, a Jamaican-American who has run a moving company right next door since 1991, told us, “I remember Mrs. Tolliver. She owned all three of these buildings right here. She lived upstairs and her daughter used to come and take care of her. The third building, right there, that was Ben’s Barber Shop – his place was special.” Today it’s a small deli run by recent Yemeni immigrants.

On the south corner is an old faded wooden sign that announces Marie’s Fish & Chips. Tyler Green, whose parents owned the business, recalled a different neighborhood. “When I was coming up, this neighborhood was full of Germans and Blacks. And my parents ran this fish and chips takeout.” She remarked, “You like my sign, don’t you? My neighborhood loves that sign. All of the signs used to be hand made by a local artist. I keep it up because it’s a kind of landmark of sorts.” When asked about Tolliver’s, Green recollected, “Oh yeah, I remember. Tolliver’s used to be a great spot. Fats Waller used to play, Count Basie lived in Queens, Lena Horne, James Brown…lots of great musicians and singers came through and a bunch lived and played here, right here, at Tolliver’s.”

On the south corner is an old faded wooden sign that announces Marie’s Fish & Chips. Tyler Green, whose parents owned the business, recalled a different neighborhood. “When I was coming up, this neighborhood was full of Germans and Blacks. And my parents ran this fish and chips takeout.” She remarked, “You like my sign, don’t you? My neighborhood loves that sign. All of the signs used to be hand made by a local artist. I keep it up because it’s a kind of landmark of sorts.” When asked about Tolliver’s, Green recollected, “Oh yeah, I remember. Tolliver’s used to be a great spot. Fats Waller used to play, Count Basie lived in Queens, Lena Horne, James Brown…lots of great musicians and singers came through and a bunch lived and played here, right here, at Tolliver’s.”

Editor’s note: In this two-part installment of our monthly series on migrant kitchens in Queens, NY, told through interviews, photos, maps and short films, we look at the migration of African-Americans to the borough. Additional funding for this piece was provided by the Buenas Obras Fund.

Published on March 31, 2016

Related stories

June 19, 2019

AthensThe downright whimsy of Filomila is hard to ignore – or resist. Perhaps it is the red exterior with the French-inspired script or the vintage bric-a brac and posters that cover the walls. Or it could very well be the sight of all the pies, sitting patiently by the window just asking to be eaten.…

June 8, 2016

IstanbulIn Istanbul, there is a single neighborhood where one can find Uzbek mantı, imported Ethiopian spices and hair products, smuggled Armenian brandy, Syrian schwarma and sizzling kebap grilled up by an usta hailing from southeast Turkey’s Diyarbakır. Kumkapı – a shabby seaside strip of century-old homes, Greek and Armenian churches and residents from a vast…

April 17, 2013

Mexico City | By Ben Herrera

Mexico CityUpdate: This spot is sadly no longer open. Come Sunday, we often find ourselves strolling through leafy Parque Sullivan, which hosts Mexico City’s largest outdoor art market. The art here ranges from modern to whimsical, abstract to landscapes, created by artists who no doubt have dreams of being the next Diego Rivera or Frida Kahlo.…