Perhaps nowhere else is it clearer that as many as one million Syrians have settled down in Istanbul than in the city’s historic Fatih district. The neighborhood is home to the city’s immigration headquarters (Fatih Emniyet), and the backstreets leading up to it are among the most transformed, since Syrians and other new arrivals end up spending hours there, often taking multiple trips to the office to get their paperwork in order.

A stroll down the area’s Aksemsettin Caddesi reveals a dwindling number of Turkish markets and a rising number of Syrian ones, a collection of Syrian fast food joints, one Yemeni establishment and one eatery that transports its patrons through time and space, serving up dishes that in the past rarely made an appearance outside of the Syrian home kitchen.

“The first time I ate at Saruja I asked the waiter, ‘Do you have waraq enib?’” recalled my Syrian friend Muhammad Abunnassr, who is deeply loyal to the restaurant. The grape leaves stuffed with spiced ground beef and rice, slowly stewed for hours with garlic and lemon and beef broth are a labor-intensive classic, usually relegated to the home kitchen. “They said yes. I asked if they had sheikh il mihshi” – zucchini stuffed with spiced ground beef swimming in a warm, comforting yogurt sauce – “and they said yes.”

“I had been craving these foods for three years,” Muhammad said, counting the years since he left Syria. “When I tasted them, I remembered my childhood … the happy days [in Syria] when we used to have big meals at my grandma’s house,” he said with a pang of nostalgia.

That’s not a coincidence. Saruja’s owner, Bilal Khalaf, ensured that the food tasted as close to his mom’s as possible. For a full month before Saruja opened its doors, Khalaf ran taste tests daily, inviting his brother and friends to give feedback. “My mom was here at the time and I’d bring her to try the food.” Khalaf’s mother had been visiting from their hometown of Damascus, where she still lives.

“One day she’d say there’s too much spice or too much cumin or too little salt,” he recalled, “and we kept going until it tasted just right.”

Syrian home cooking takes a lot of time, labor and love, and so Khalaf was very careful in selecting his head cook. “I interviewed a lot of chefs because I knew what I wanted to focus on in terms of Damascene food.”

Dishes with a base of hot yogurt are a mainstay at Saruja and the ultimate Damascene comfort food, as compared with the creative kebabs and kibbehs (oblong dumplings with a shell base of bulgur, often stuffed with ground meat but sometimes vegetarian) from Aleppo. Where the cuisines from Syria’s two largest cities collide beautifully is in a dish like kibbeh labaniyyeh – the dumplings made with spiced ground beef or lamb and pine nuts, served in a silky smooth yogurt sauce.

“Thankfully, when we were younger my mom would have us help her in the kitchen,” he added. Rarely are dishes from the home kitchen served in Syrian restaurants, but as Syrians have become unstitched from their usual communities and flung far from their moms and grandmas and aunties, Khalaf knew there would be a demand for home cooking. He knew from personal experience.

Until 2013, Khalaf ran computer stores throughout Syria and in the United Arab Emirates, where he, his wife and his three daughters were living. But as Syria spiraled deeper into political and economic crisis, his shops were shut down, and eventually he had to sell the rest of what he had to survive. “I ended up sending my wife and kids to Istanbul because life in the UAE was too expensive,” he recalled with deep sadness. With no job and his family far away, he’d eat at a Syrian restaurant in Sharjah – an emirate in the UAE with a significant Syrian population – called Khobz wa milh, the Arabic version of “breaking bread”.

“The owner became a friend and knew me well … he knew I was jobless and very down, so he offered for me to manage the restaurant,” he explained. “To distract myself from how much I missed my wife and kids,” Khalaf recalled, pausing to swallow back tears at remembering that painful period, “I’d spend as many hours as possible at the restaurant, scrubbing the corners of the walls with my own hands.”

The eatery became successful under Khalaf’s management, and the owner offered to finance another restaurant. “I told him I wanted to open it in Istanbul.” And so, Saruja was born.

Khalaf put deep thought into every detail – even the eatery’s name. Saruja is the oldest part of Damascus outside the city’s ancient city walls and the first place the Ottoman Turks settled when the empire expanded into the Levant in the 16th century, he explained.

Beyond classic starters such as hummus, falafel and mutabbal (a smoky eggplant dip with tahini and garlic) found in Levantine restaurants across the globe, Saruja serves a few fixed dishes for lunch and dinner every day, plus a rotating menu of daily specials. Saturdays are for sheikh al mihshi, my friend Muhammad’s favorite, and the waraq enib are now served every day.

Any day of the week one can also order the kibbeh labaniyyeh, and while it tasted so close to the version I had growing up from my grandmother’s kitchen, there was a pinch of something special that took the dish from great to “foodgasmic,” as Muhammad calls it.

“Ah, there’s a secret ingredient,” our friendly waiter, Ayman, joked with a broad smile. “Our chef adds a small topping of garlic and cilantro.” He added that the flavorful garnish is unique to Damascus. The combination of sautéed garlic and cilantro is a mainstay of many Damascene dishes, but rarely is it incorporated into the hot yogurt sauce that defines Syrian comfort food.

And with that comfort food comes a comforting environment. The distinct masculinity that can define the usual Middle Eastern eatery is softened, embodying Khalaf’s own gentle, but dignified persona. The service is warm and welcoming, and the servers dish out their smiles as generously as they do Saruja’s delicious meals.

Khalaf says his goals are to represent all the good things Syrians have to offer to their new home city. Even more, he wants Saruja to serve as a dining room for the homesick.

February 9, 2017 Francesinha

February 9, 2017 Francesinha

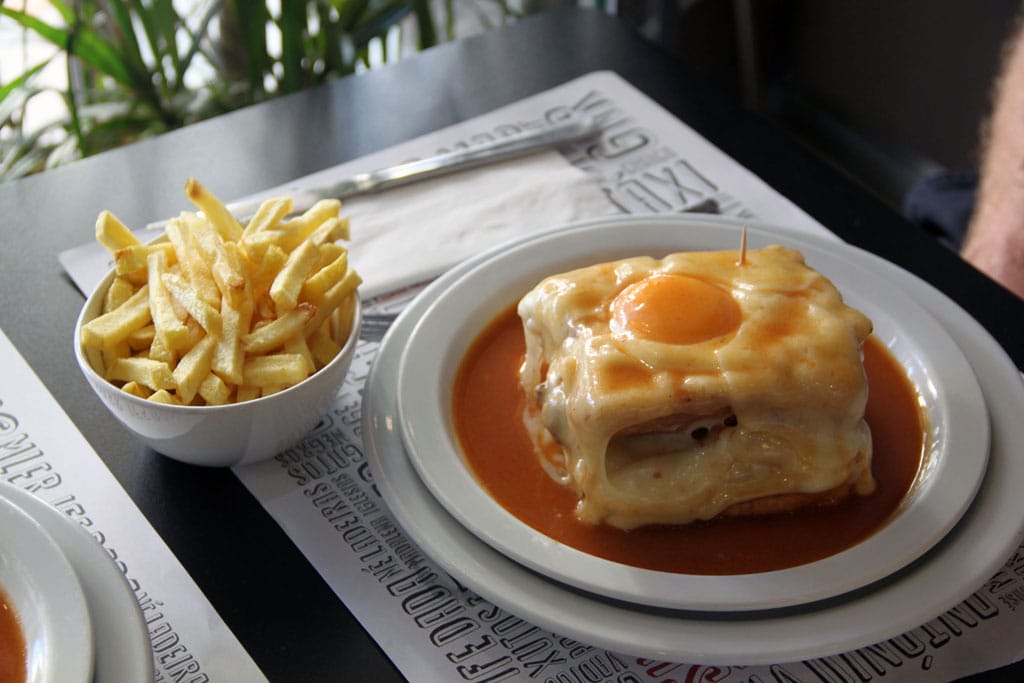

A gloppy, meaty, cheesy brick served in a pool of sauce and with a mountain of fries: […] Posted in Porto May 3, 2017 Keti’s Bistro

May 3, 2017 Keti’s Bistro

Going out for a Georgian dinner in Tbilisi used to be a predictable, belt-popping […] Posted in Tbilisi July 29, 2014 Azerbaycan Sofrası

July 29, 2014 Azerbaycan Sofrası

Looking at a map of the southern Caucasus, you’d expect Azerbaijan to be the next big […] Posted in Istanbul

Published on April 28, 2017

Related stories

February 9, 2017

PortoA gloppy, meaty, cheesy brick served in a pool of sauce and with a mountain of fries: please meet the francesinha, the culinary pride and joy of the city of Porto. Today, restaurant billboards proclaim in many languages that they serve the best version in the world, revealing the genuine power of this artery-clogging combination…

May 3, 2017

TbilisiGoing out for a Georgian dinner in Tbilisi used to be a predictable, belt-popping affair. There were very few variations on the menus of most restaurants, all of which offered mtsvadi (roast pork), kababi (roast pork-beef logs), ostri (beef stew) and kitri-pomidori (tomato-cucumber) salad. To open a restaurant and call it Georgian without these staple…

July 29, 2014

IstanbulLooking at a map of the southern Caucasus, you’d expect Azerbaijan to be the next big thing in the world of food, sandwiched as it is between culinary heavyweights Georgia and Iran, connected as it is in so many ways to Anatolian Turkey. Previous trips to that country have not delivered, though. The last time…