All things considered, bread is a relatively new arrival in Japan, having found its way there in 1543, when the first Portuguese ship arrived carrying missionaries and merchants who had come to spread the word of God and seek new markets.

These Europeans brought with them commodities both tangible and intangible. When the Sakoku Edict, which essentially closed Japan to all international contact, came into effect in 1635, some of these commodities remained in one form or another. The vast majority of Japanese would never encounter bread during the subsequent Tokugawa Era (1603-1868), though the concept of doughy baked goods – pan in Japanese, from the Portuguese pão – remained.

When the Meiji Restoration widened Japan’s doors to Western trade in 1868, the first Japanese bakeries began to open and soon numbered in the thousands. In this new modern era, Japanese consumers viewed bread as more of a Western-style sweet than a staple, in part because rice had long stood – and still stands – as the island nation’s main grain. This perception shaped the country’s greatest contributions to the bread world, as the most distinctly Japanese doughy delights remain sweet in nature.

Genuine Japanese breadstuffs are not the stuff of fiction.

After World War II, bread became a symbol of American occupation. Despite this negative association, consumption climbed steadily in the following decades. Bakeries became more common in the 1990s, and domestic bread consumption jumped nearly 8.5% in 2010 alone. This growth even inspired a popular manga, Yakitate!! Japan, about a young baker with the singular ambition of creating a bread for Japan as important and beloved as the baguette is in France. Genuine Japanese breadstuffs, however, are not the stuff of fiction. Here are our top three picks for truly Japanese baked goods, as well as the best place in the country’s capital to find them.

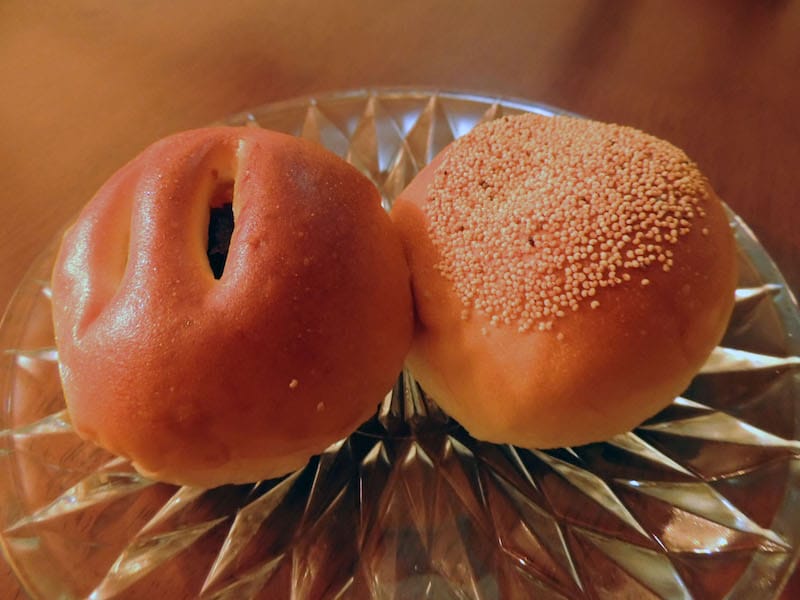

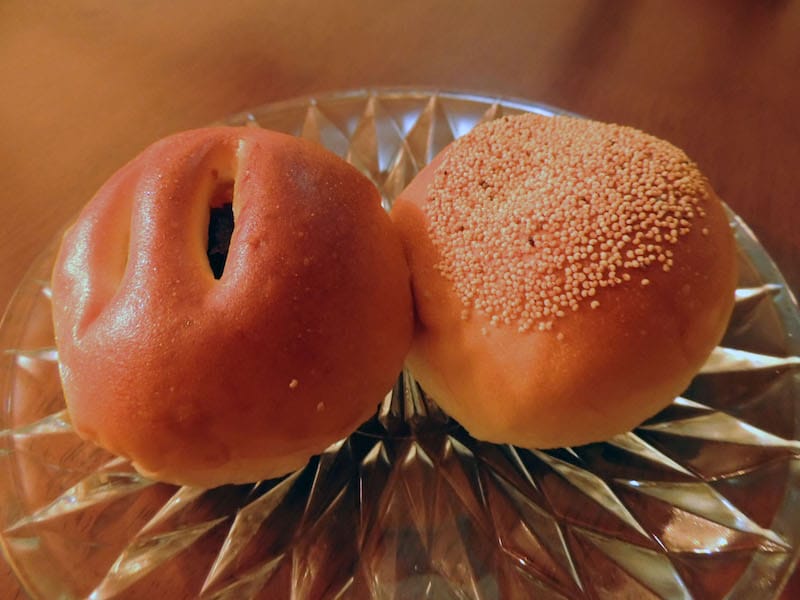

Former samurai Yasubei Kimura invented anpan (sweet dough rolls stuffed with sweet bean paste) in 1874 and began selling them at his bakery, Kimuraya, in Tokyo’s glitzy Ginza neighborhood. The following year, no less a personage than Emperor Meiji took a liking to Kimura’s confectionary creation, thus sealing anpan’s place in culinary history. To this day, Kimuraya maintains its reputation for baking the capital’s best anpan, which comes in several varieties. We recommend the keshi anpan, anpan topped with toasted poppy seeds.

If bean past isn’t your thing, consider the humble meronpan, also written as melonpan (melon bread), a sweet bun covered in a thin, crispy layer of cookie dough. The name comes from its resemblance to a melon, not its flavor, though many bakers have embraced the misconception and created melon-flavored meronpan. Other popular flavors are black tea, cinnamon and chocolate chip. Tokyo’s best melon bread can be found at Kyuei in the bayside neighborhood of Tsukishima. Freshly baked meronpan from Kyuei is an ideal dessert after dinner at one of the neighborhood’s hundred or so monjayaki restaurants. (We’re especially fond of Kondo Honten.)

For something savory, try kāre pan, Japanese curry wrapped in dough, coated in breadcrumbs and deep-fried. Japanese curry is thicker and milder than its mainland counterparts, as it’s made from roux and curry powder rather than blended spices. Biting into a good kāre pan can be a near spiritual experience: Crispy fried crust gives way to satisfying, chewy dough before reaching the spicy center of curry roux. With kāre pan, what’s inside counts just as much as the bread itself, so it should come as little surprise that Tokyo’s best is from a curry shop, not a bakery. J.S. Curry in Shibuya has a take-out window so you can grab a bun on the go, but we recommend sitting down inside, in which case your order of kāre pan will be fried up fresh and served piping hot. They have both a classic kāre pan, as well as one with spinach and mozzarella cheese.

This article was originally published on August 16, 2017.

April 12, 2024 Lil’ Dizzy’s

April 12, 2024 Lil’ Dizzy’s

Don’t be fooled by the name of Lil’ Dizzy’s Cafe. There’s no coffee, and in fact, the […] Posted in New Orleans May 7, 2020 Shanghai In Recovery

May 7, 2020 Shanghai In Recovery

It’s 9 p.m. at Fu Chun Xiao Long, and the waitress taps me on the shoulder to let me […] Posted in Shanghai February 5, 2016 Auspicious Eating

February 5, 2016 Auspicious Eating

As the moon starts to wane each January, people throughout China frantically snatch up […] Posted in Shanghai

Published on November 12, 2020

Related stories

April 12, 2024

New Orleans | By Joshua Levkowitz

New OrleansDon’t be fooled by the name of Lil’ Dizzy’s Cafe. There’s no coffee, and in fact, the iconic establishment feels more like an auntie’s overstuffed living room than a café. Situated in the heart of Tremé, the oldest African-American neighborhood in America, Dizzy’s is crammed with family paintings and inauguration memorabilia for President Barack Obama,…

May 7, 2020

ShanghaiIt’s 9 p.m. at Fu Chun Xiao Long, and the waitress taps me on the shoulder to let me know they’re about to close. The Shanghainese snack shop has been serving up xiaolongbao (soup dumplings) and paigu niangao (deep-fried pork cutlets and rice cakes in gravy) until midnight for decades. But in the post-Covid-19 world,…

February 5, 2016

ShanghaiAs the moon starts to wane each January, people throughout China frantically snatch up train and bus tickets, eager to start the return journey to their hometown to celebrate the Lunar New Year (春节, chūnjié) with their family. This year, revelers will make an estimated 2.5 billion journeys on the train system alone, up 100 million from…