“It’s good for tourists, not for us.” While this can sadly be said about many things, Anabela, the woman we are speaking to, is referring to the transformation of Mercado da Ribeira, Lisbon’s historic public market, where she co-runs a small grocery store.

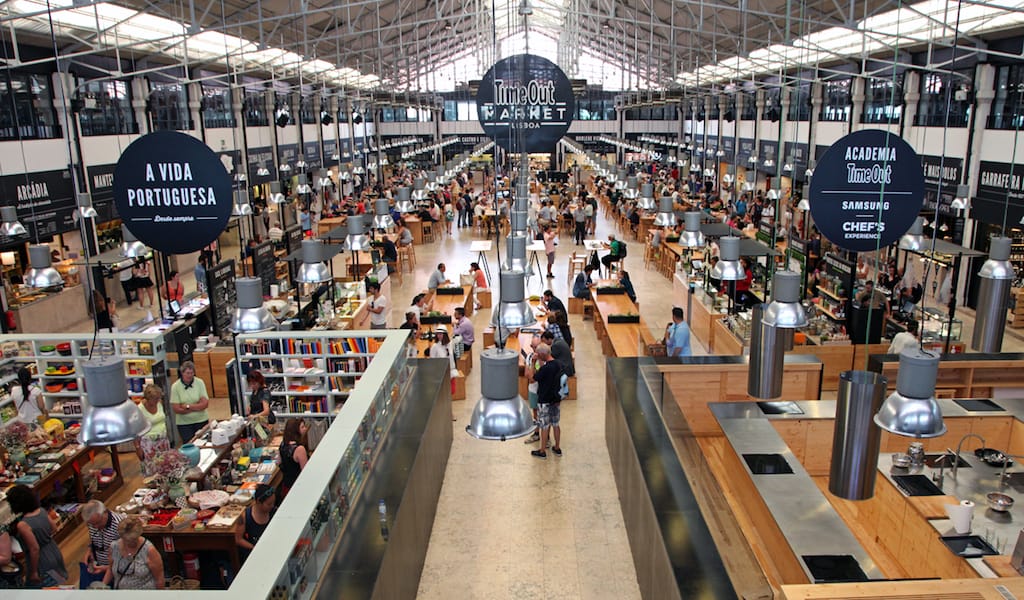

Originally built as a predominantly wholesale food, fish and flower market in 1771, Ribeira today shares its space with Mercado Time Out, financed by the venture capital firm that controls the publishing franchise in Portugal, which has occupied the central section of the market since 2014. Time Out’s concept: an “editorially” curated gourmet food hall. Selling the best of Portugal – from croquettes and custard tarts to seafood and steak – it is now a top attraction, with 24 restaurants, eight bars, a dozen shops and a high-end music venue.

The success of the site means that three more Time Out Markets – in Chicago, Boston and Miami – will open by 2019. London is also scheduled to get its own Time Out Market, despite initial plans for a market in historic Spitalfields being rejected by the local town council.

Anabela, alongside partner Joaquím, runs Loja 54, a cheerful store that has been here since the 1950s. Many of their neighboring vendors along the corridor have left, some now selling in markets 20 kilometers away. The shop’s loaded shelves stock bacalhau (salted cod) and everyday items as well as tinned food, oils, sauces and grains from Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique. “We have been surviving because our products cater for the African community here,” says Joaquím. “But our plan for the future is to close down.”

It makes sense that Time Out’s new concept started here. The venture took advantage of a central but neglected locale, partly abandoned real estate, a malleable public administration reeling from financial crisis and, crucially, a lot of food-related hype – many of the new eateries are fronted by individual chefs.

“In Lisbon now, ‘star chefs’ are the new starchitects,” says Paula André, professor of urbanism and architecture with a focus on the capital city at the University Institute of Lisbon. “The transformation of the markets, and even some neighborhoods, follows the logic of this new urban dynamic. They are examples of where, instead of being used to enhance the identity of the neighborhood, an international model is applied.”

“There’s no hope for the market’s future,” she says, in a manner more matter-of-factual than lamenting.

Around Mercado Time Out’s main atrium and in a similarly sized space next door, a few die-hards are still selling traditional fare. Maria Benilde has been selling fish in Ribeira for half a century, mainly to restaurants in the nearby Bairro Alto neighborhood. “Many tourists come to walk around and see this side, but there aren’t so many people buying,” she says. She adds that the disappearance of Ribeira’s fish aisles would be a “disgrace.” Her produce, she proudly says, is better and cheaper than what’s found in the supermarkets.

The decline of the traditional market in Lisbon began with the introduction of supermarkets and hypermarkets in the 1990s, first in the outskirts before expanding to the center. As Loja 54’s Joaquím puts it, “traditional commerce in Portugal has no protection.” An increase in the number of competitors – as well as the chronic lack of parking in the center – is a big part of the problem.

“Lisbon markets actually have a huge potential to promote regional food,” says Professor André, “because there is a strong national diversity. They could also be used to make a connection with the growing number of urban community gardens here, making them a meeting point for young people. As it is, I cannot imagine [traditional] markets existing in 10 years time.”

Left Hand Rotation, the collective name for a duo of artists based in Lisbon that has been using video to document issues of urban transformation since 2005, feels similarly. “It is local economies that suffer when markets change,” they say. Their project and resulting film, Permanecer en La Merced, focuses on political corruption in Mexico City’s largest traditional food market and its battle to remain a public space, and many of the issues they observed there resonate in Lisbon. “Maybe in Europe this [change] is not very evident because market transformation has been happening here longer. But the case of Mercado da Ribeira was particularly cruel, because a few original artisan sellers [many making crafts to sell to tourists] were prohibited to sell their products.” The duo, who often collaborate with other artists and activists, argues that the initial abandonment of Ribeira, located in a formerly neglected riverside locale, marked the beginning of its extreme gentrification. “After Time Out, all the surroundings went chic.”

Mercado Time Out is not the only regenerated market in Portugal. The city of Porto’s Bom Sucesso became more or less a shopping mall in 2013. Lisbon’s Campo de Ourique and Mercado de Algés were also upgraded after that. The latter, originally built in the 1950s, is towered over by crumbling buildings and surrounded by land soon to be made into pedestrian space. Half of the market is occupied by reconstructed classic vegetable and fish stalls, the other half a new food court – a model expected for Porto’s iconic Mercado Bolhão, next on the list.

Porto’s mayor, Rui Moreira, has publicly criticized Lisbon’s Time Out Market, promising that Bolhão will be kept “as a market, not a food court,” despite plans to make the upper levels into restaurants. Though it cannot be enforced, the idea is that they will buy from the traditional market vendors downstairs, keeping them in business.

A large woman with a knife in her hand screaming fish prices in your ear is a unique experience in Portugal, and one that has been going for centuries. A traditional market like Ribeira or the neoclassical Bolhão, with their late-night cafés at the entrance and gossiping groups of sellers, are places of rich social connection. But in Lisbon’s residential Graça area, for example, Mercado Sapadores is a semblance of its former self. A few stalls still sell fish, fruit and vegetables every morning, but several stand empty. According to Beatriz, who has been selling here for 40 years, there are rumors that it will be turned into a health center. “There’s no hope for the market’s future,” she says, in a manner more matter-of-factual than lamenting. Better a health center, perhaps, than other alternatives – in the neighborhood of Alcantara, the municipal market is now mostly occupied by the German supermarket LIDL.

“It’s difficult to find a solution for the public market without a larger, economic change,” Left Hand Rotation says. The group points out a less gloomy situation in Madrid. “The EVA (Espacio Vecinal Arganzuela) market in Usera was slowly dying, but then the neighbors took over. It has been transformed into a space used for social activities – workshops on digital empowerment for women; language courses for migrants; talks on sustainability, small enterprise and business strategies; kids activities; etc.”

The example of EVA could be somewhat utopian in the context of Lisbon – there’s little the city’s residents can do in the face of the corporate logic sweeping the Portuguese capital and the new capital flowing into it. As well-heeled tourists and cosmopolitan expats replace the original residents in certain parts of Lisbon, it seems that the need for a public marketplace has been replaced with the desire for a new kind of “authentic” yet ultimately artificial curated experience – one that celebrates market life as it simultaneously strips away so many of the elements that make it worth celebrating in the first place.

April 25, 2019 Meet the Vendors

April 25, 2019 Meet the Vendors

It’s 5:20 in the morning and while most lisboetas are still sleeping, Lurdes and […] Posted in Lisbon February 10, 2021 Balmerkez

February 10, 2021 Balmerkez

Wandering around the neighborhood of Çarşamba, home to a famous weekly market and close […] Posted in Istanbul July 27, 2019 Summer Picnics

July 27, 2019 Summer Picnics

Athens, unofficially known as the Big Olive, has many delightful spots for a picnic in […] Posted in Athens

Published on March 16, 2018

Related stories

Taste the very best seasonal seafood on our Song of the Sea walk!

April 25, 2019

LisbonIt’s 5:20 in the morning and while most lisboetas are still sleeping, Lurdes and Ermelinda Neves are already arriving at the Mercado da Ribeira in the Cais do Sodré neighborhood. Cooks and chefs from Lisbon’s restaurants start showing up at this central market at 6 a.m., and these two seafood sellers need to prep their…

February 10, 2021

Istanbul | By Lorenza Mussini

IstanbulWandering around the neighborhood of Çarşamba, home to a famous weekly market and close to the sprawling Fatih Mosque complex, we get the distinct impression that this area is honey central: the streets are lined with shops selling the sweet nectar, particularly stuff coming from the Black Sea region. “This area is full of honey…

July 27, 2019

AthensAthens, unofficially known as the Big Olive, has many delightful spots for a picnic in all seasons. Okay, in summer perhaps you’d rather be on the beach – and that can be arranged if you hop on a bus or tram for the southern coastal suburbs of Voula, Vouliagmeni and Varkiza – but in the…