Editor’s Note: Though integral elements of Lisbon life, communities from Portugal’s former colonies can sometimes be an invisible presence in their adopted land, pushed out to the periphery. With our “Postcolonial Lisbon” series, CB hopes to bring these communities back into the center, looking at their cuisine, history and cultural life. In this installment, we dive into Lisbon’s Goan community.

Vasco de Gama’s voyage to India in the late 15th century laid the groundwork for the Portuguese empire, in which Goa, a small region on the southwestern coast of the Indian subcontinent with ample natural harbors and wide rivers, would come to play an important role. In the early 16th century, Goa was made the capital of the Portuguese State of India and remained as such until 1961, when the Indian army captured it.

Over four centuries of colonial rule, Goan intellectuals most often migrated to Portugal in search of education, especially in the 20th century. Yet following the annexation of Goa by India, many Goans, particularly those working in government and the military, accepted the state’s offer of Portuguese citizenship and made their way to Europe. Others migrated to Mozambique, another Portuguese colony that at the time had not yet gained independence.

Taste Goa in Lisbon: Zuari

While Delícias de Goa, a favorite traditional Goan restaurant of ours, is now closed, another lives on in the form of Zuari. Orlando Rodrigues has been at the helm of Zuari in the Lapa neighborhood for almost half a century now. All of his family is from Goa, which was the only home he knew until 1961, when it was annexed by India. He didn’t feel comfortable with the new order and moved to Mozambique. “I was Portuguese, too, and felt better there,” he explained.

In Mozambique, he joined the military and then worked as the manager of Hotel D. Carlos in the city of Beira until 1976. At that point, working conditions became difficult and he decided to make his way to Portugal.

But here the situation was also complicated. “When I arrived in Lisbon, the city was so full of retornados [the returnees, or refugees that fled from Angola and Mozambique after 1975] that I had to go all over the country to find a place to stay and work. I even slept on the beach in the Algarve,” he said.

He eventually settled in Ericeira (45 minutes north of Lisbon), where he opened a small spot in 1977, but it was only profitable in the summer. “Then I started Zuari here,” he explained, “and thank God I always have a house full of people.”

Many regulars are partial to their shrimp curry or the fish curry, both of which require a lot of work and dedication. But the restaurant is perhaps most famous for its chamuças (samosas), which customers used to be able to get to go. “I had one person in my family doing them and she helped me when I started my business here. At one point we were doing 12,000 samosas a week, and I had seven people working on this,” Orlando said.

Due to a change in European health and safety laws that required deep-freezing of such snacks, a large and costly operation that he didn’t have the capacity for, Orlando closed the takeaway section. But he and his wife still make chamuças from scratch for his small restaurant in Lapa. “It’s a lot of work, stretching the dough to get it thin,” he said. Their version is stuffed with beef (and plenty of it), and the end result is crunchy and delicious.

Following the annexation of Goa by India, many Goans, particularly those working in government and the military, accepted the state’s offer of Portuguese citizenship and made their way to Europe.

The Goan/Portuguese fusion can be seen in most dishes but vindalho represents probably the best celebration of both continents. “The dish here in Portugal was vinha d’alhos [a marinade of pork with wine and garlic] but the Portuguese started to use vinegar as there was not wine in Goa, and then the cinnamon, cloves and all the spices,” Orlando explained. For the rest of the world, particularly in the United Kingdom, this dish became known as vindaloo, a hotter, fierier version where the chili peppers dominate all the flavors, and the sweet elegance of the cinnamon and cloves are lost.

Orlando is proud of his small restaurant, which is named after a river in Goa. A stream of regulars, neighbors, politicians, members of the parliament and chefs come to eat and converse with him.

His entire family toils away to keep the restaurant running, and that’s why they always take the month of August off, shuttering the restaurant’s doors. But sometimes Orlando mixes business with pleasure. “When I go to Goa on holidays, I always bring spices for one or two years. I grind them here and they are completely different from the ones we find in packages,” he said.

His specialties also include homemade mango ice cream, the recipe for which a big food company tried to buy a few years back, and the difficult yet rewarding bebinca, a multi-layered cake that is made with 40 egg yolks and coconut milk. It takes a full day of work to bake the separate layers, in an uneven number of seven or nine. “It’s a traditional Goan dessert for Christmas/New Year’s Eve from a nun’s recipe,” he explained. This is fusion at its best: the convent baking tradition from Portugal, which features lots of egg yolks, reimagined using local ingredients such as coconut milk and nutmeg.

Zuari is a family affair: Orlando told us that he was always very curious about what his mother was cooking. It must run in the family, as his daughter and his son help him in the restaurant.

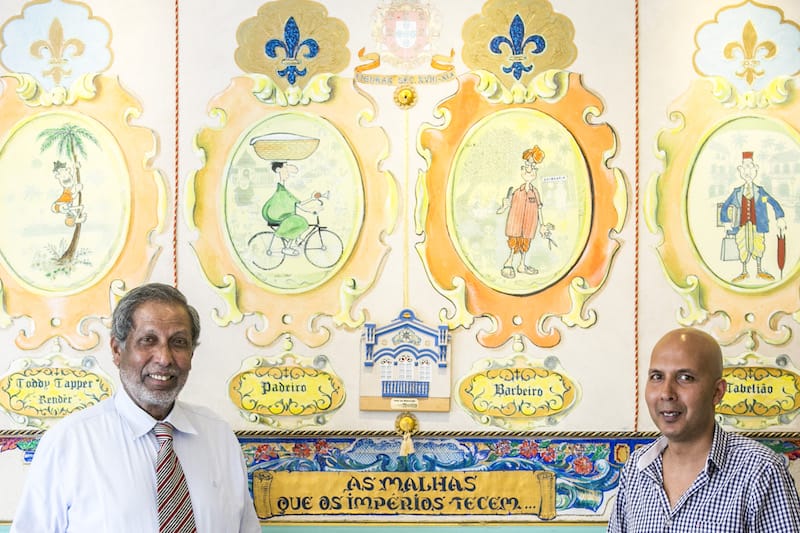

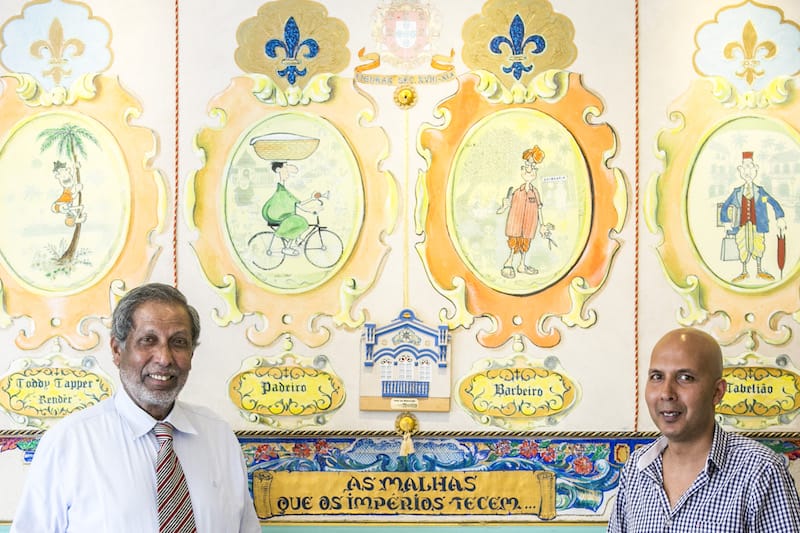

Basílio Fernandes’s Chamuças

While Zuari no longer offers takeaway chamuças, they have become an ubiquitous snack across Lison. No one perhaps knows the chamuça business better than Basílio Fernandes. Born in Goa in 1951, he came to Lisbon with his parents when he was just a one-year-old. Growing up in Lisbon, he remembers an already established Goan community here, mainly consisting of lawyers, doctors and other professionals. (Basílio himself has connections in high places – he’s a friend of the current Prime Minister of Portugal, António Costa, whose family is of Goan origin.)

Basílio’s father, whose name is also Basílio Fernandes, founded Velha Goa, considered to be the first Goan restaurant in Lisbon, in the early 60s. At that time, it was difficult to source the spices and ingredients necessary to make Goan food. They had to be imported from London, unlike today where they can easily be found in the Martim Moniz area.

For years, the restaurant attracted a crowd to the Campo de Ourique neighborhood. They came to taste the Goan specialties, like vindalho, a dish with Portuguese origins that Goans made their own by using vinegar (not the traditional wine or olive oil) and cumin, clove and cinnamon to preserve and cook the meat. The delicious chamuças, though, were particularly beloved.

Basílio and his brothers left university to help their father as the restaurant grew more popular. Eventually, after teaching all of his recipes to his kids, he decided to leave the business. “My father handed me the keys, saying he wanted to retire,” Basílio said.

A musician himself and later a manager and producer for many top Portuguese musicians, Basílio began to host gigs at the restaurant. “We had live music in Velha Goa when there were no other clubs in the city, except Hot Club,” he said. It was exciting but also very tiring to run such an enterprise, and Basílio decided to retire at 55 years old. “I was exhausted,” he admitted. And so, 11 years ago, Velha Goa closed. “I went to Goa, where I didn’t have to do chamuças,” he said, laughing.

For family reasons, he eventually returned to Lisbon and rented an apartment next to Padaria do Povo, an association in Campo de Ourique, and started to make vegetable chamuças for them in his home kitchen. But demand was so high for these savory snacks that he opened a small restaurant and takeaway.

“Now I have too many clients and I just want to go back to Goa,” he said while showing us his little farm in Costa da Caparica where he grows the different hot chile peppers, vegetables and herbs used in his dishes and sauces.

What began as a popular dish at Goan restaurants has gone mainstream. Nowadays you can find chamuças at snack bars, cafés and supermarkets all over the country. “It’s a big business,” said Basílio of these mass-produced samosas. Yet on the flipside, the snack is now so commonplace that other chefs are tinkering with the chamuça formula, like the Mozambique-inspired fish and spring samosas at Ibo or the special sardine samosas that Goan Jesus é Goês made for one of the Santo António festivals, further deepening the cultural exchange and cementing the cultural links between Goa and Portugal.

Read more about the Goan community and history in Lisbon – as well as the popular chamuça– in the dropdown below.

Published on June 27, 2022

Go Deeper

- Learn more about the history of the Goan community in Lisbon

- In the early 16th century, Goa was made the capital of the Portuguese State of India and remained as such until 1961, when the Indian army captured it. This led many Goans, particularly those working in government and the military, to accept the state’s offer of Portuguese citizenship and made their way to Europe. Others migrated to Mozambique, another Portuguese colony that at the time had not yet gained independence.There was always a close connection between the two states, as Mozambique used to be within the jurisdiction of the viceroy of India, and many Goans worked there, first as merchants and later as administrators and clerks. Moreover, Goa was famous for its medical and pharmacy school, and the doctors and pharmacists that trained there often took jobs in other Portuguese colonies.

Yet when the African state finally threw off Portuguese rule in 1975, many of the Goan transplants found themselves with few opportunities. It’s estimated that around 10,000 Goan families moved to Portugal after the decolonization of Mozambique and Angola.

In recent years, Goans have been migrating to Portugal under the law that allows those born in Goa (as well as Daman and Diu, also part of Portuguese India) before 1961 or their descendants up to the third generation to become Portuguese citizens.

Yet given these many waves of migration and assimilation over the years, it’s difficult to determine how many Goans are currently living in Lisbon. According to the Report of the High Level Committee on the Indian Diaspora put together by the Indian government in 2001, there are around 70,000 Indians in Portugal, including those with ancestral ties to the Indian subcontinent and recent immigrants.

- The chamuça, a symbol of Goa in Lisbon

- What is clear is that as more Goans migrated to Lisbon during the 1960s and 70s, particularly after Mozambican independence, their cuisine began to trickle into the public sphere. Prior to 1961, the year that Portuguese rule ended in Goa, Goan food was not prevalent in Portugal and could only be found in private homes.

One snack in particular – the chamuça, or samosa – conquered Lisboetas, eventually becoming the most beloved Goan specialty in the city. The rise of the chamuça is a unique lens through which to track the history of the Goan community in Lisbon.

According to Dr. Erica Wald, Senior Lecturer of Modern History at the University of London, the samosa “is of contested origin.” Some say the Portuguese introduced samosas, along with myriad other ingredients (potatoes, chilies, peanuts and maize, to name a few), to India, having learned how to create the thin wrapping from the Moors. Others, like Rui Rocha in his book A Viagem dos Sabores (“The Journey of Flavors”), attribute this type of dough to the Chinese. There is also an argument to be made, as Colleen Taylor Sen does in her book Feasts and Fasts: A History of Food in India, that the samosa came from the various Middle Eastern cuisines that the Mughals embraced when they ruled India.

While all types of samosas are available in India today, vegetable samosas are the most common. “Partly, this is because there are so many vegetarians. Also, meat is more expensive than vegetables,” said Chitrita Banerji, a Bengali-American food writer and author of Eating India.

José Paula Rodrigues, owner of the now-shuttered Lisbon restaurant Delícias de Goa, recalls eating lots of shrimp samosas in Goa. For him, samosas were an integral part of daily life in both Goa and Mozambique, where he lived from 1967 until 1975. At the end of the day, people would gather on terraces to drink beers and boys with baskets full of chamuças would invariably show up to peddle their wares.

It was mostly after 1975, when Goans began arriving from Mozambique, that the chamuça started to gain popularity in Lisbon. It was the first “foreign” snack to take up real estate next to cod cakes and meat croquets on fry trays at shops and restaurants. Yet rather than the vegetable and shrimp chamuças that were so prevalent in Goa and later Mozambique, meat ones became the favorite in Portugal. What began as a popular dish at Goan restaurants has gone mainstream. Nowadays you can find chamuças at snack bars, cafés and supermarkets all over the country.

- Learn more about Goan cultural spots in Lisbon

- In 2017, Casa de Goa celebrated its 30th anniversary in Lisbon. Located in Alcântara, it’s a cultural hub for Goans in Lisbon, keeping both traditions and memories alive. Besides a library and museum, there’s a restaurant – currently closed but soon to re-open – and regular events, conferences, exhibitions, games, social gatherings and food workshops.

Casa de Goa is particularly active in promoting traditional Goan music and dance: it hosts a folk dance group called Ekvat and the music group Gâmat. Jerónimo Aráujo e Silva is the musical director and also the composer of some of the original songs. The repertoire includes traditional Goan music but also popular and classic Portuguese numbers.

The groups are open to new members, as one of Casa de Goa’s main goals is to acquaint young people with the culture of their parents and grandparents. Valentino Viegas, from Casa de Goa, regrets that there aren’t more young people participating in the association’s events. “We need new generations to get involved and to continue our legacy,” he said.

Edgar Valles, who led the association for four years until April 2018, noted that when it was first established, Casa de Goa didn’t have any contact with Junta de Freguesia da Estrela (the closest municipality department), the Indo Portuguese Friendship Society in Goa, or even with the Goan government. Now there’s cooperation across continents.

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the association, Ekvat staged a show at Teatro Tivoli. The dance covered many traditional styles from the mandó, which is sung and danced in aristocratic Goan households, to the fugddi natch, a playful and rhythmic dance that was traditionally performed by farm workers.

Related stories

August 24, 2023

LisbonAs we shoot dishes in Criolense Kitchen Club, drawing attention as photography often does, we get the distinct impression that locals passing by are noticing the space for the first time. It’s possible they hadn’t noticed this bar/restaurant in Lisbon’s Graça neighborhood because, well, it has no sign. Criolense Kitchen Club shares space with art…

June 28, 2022

LisbonEditor’s Note: Though integral elements of Lisbon life, communities from Portugal’s former colonies can sometimes be an invisible presence in their adopted land, pushed out to the periphery. With our “Postcolonial Lisbon” series, CB hopes to bring these communities back into the center, looking at their cuisine, history and cultural life. In this installment, we dive…

June 28, 2022

LisbonEditor’s Note: Though integral elements of Lisbon life, communities from Portugal’s former colonies can sometimes be an invisible presence in their adopted land, pushed out to the periphery. With our “Post-Colonial Lisbon” series, CB hopes to bring these communities back into the center, looking at their cuisine, history and cultural life. In this installment, we…