Georgia’s winemaking tradition has been making headlines since scientists announced, after 8,000-year-old jars bearing images of grape clusters and a man dancing were excavated in a dig south of Tbilisi, that the country is home to the world’s oldest wine.

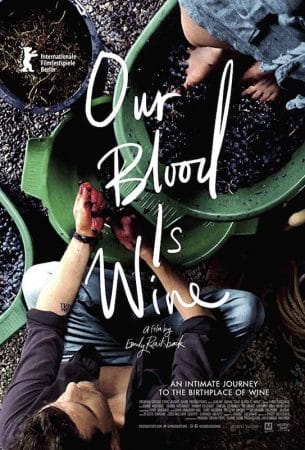

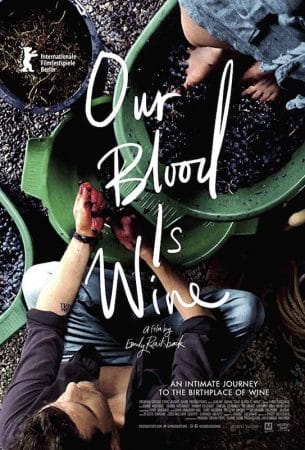

But long before this discovery was made public, filmmaker Emily Railsback and award-winning sommelier Jeremy Quinn were traversing Georgia to research the rebirth of these ancient winemaking traditions, which were almost lost during the period of Soviet rule. Railsback chronicled their deep dive into the world of family vintners and grape sleuths in the documentary Our Blood Is Wine, an official selection of the 2018 Berlinale International Film Festival.

But long before this discovery was made public, filmmaker Emily Railsback and award-winning sommelier Jeremy Quinn were traversing Georgia to research the rebirth of these ancient winemaking traditions, which were almost lost during the period of Soviet rule. Railsback chronicled their deep dive into the world of family vintners and grape sleuths in the documentary Our Blood Is Wine, an official selection of the 2018 Berlinale International Film Festival.

Impressed by her ability to bring the voices and ancestral legacies of modern Georgians directly to the viewer, we spoke to Railsback at length about her documentary in our inaugural CB Film Club feature.

How did you first get interested in Georgian wine? And how did you get connected with Jeremy Quinn?

While I was finishing my MFA in film, I worked with Jeremy at Telegraph, a wine bar in Chicago where he was the sommelier [the pair recently married]. I loved the way he cared about the stories behind each bottle of wine. He avoided all pretension and cared about each farmer and vigneron. Our wine bar was a rare one. Most of the employees had worked there for 10-20 years. A huge reason for the retention was each year the employees would get to travel to a wine region around the world. Jeremy led these trips for over a decade. His next interest was the origins [of wine], and naturally that led him to Georgia.

Large parts of the documentary were filmed in the mountains of Georgia and out in small villages. Can you tell us a bit more about your approach to shooting?

This was my first documentary film. I was used to narrative film sets where you have a very specific shot list and approach to telling the story. This project was outside of what I knew, so I tried to be open to what would unfold. I shot on the iPhone 6, because I wanted the film to feel like the viewer was experiencing Georgia first-hand. The way we did. There are so many beautiful spontaneous moments that happened in Georgia, especially the moments of singing around the table. If I hadn’t shot on such a small, familiar device I think the people we filmed would have been aware of the camera. That’s something I wanted to avoid.

For many of the winemakers in the film, making wine is a very personal thing, something done for their family and community. How did you go about building relationships with these winemakers?

Jeremy lived and worked at a wine bar in Georgia for about five months. He developed deep friendships with many of the winemakers before we conceived the idea of the film. I went to visit him in December 2014, and at that time it felt natural to tell these stories. That was due in large part to the trust they showed him.

There are lots of beautiful examples of polyphonic singing in the documentary. Why do you think this tradition is an important part of the story about Georgia’s wine culture and history?

Wine is just one aspect of the Georgian culture. However, it is woven through everything. Singing is intertwined with wine. You cannot have one with the other. I personally think it is the singing culture that helped keep hope alive during the Soviet era when vineyards were being destroyed.

At one point in the documentary, one of the winemakers asserts that Georgian wine cannot compete with the big producers and that small family producers are the way forward. What do you think is the way forward for Georgian wine?

I think the future for the world is to return to natural farming methods. Consumers are having more of an interest in this when they buy wine, which is what has given Georgia a spot on the world stage. I think if more people make wine in this method, our tastes will expand to want these “experiments.”

There also needs to be an understanding that when someone goes to a bar and says, “Give me a Pinot or a Cab,” they are helping to destroy biodiversity. We need to champion lots of grape varieties in order to support a healthy environment. I think it’s our responsibility to consciously expand our idea of taste to support a healthy earth. When our tastes are so narrow, restaurants get scared to sell rare grape varietals that are unrecognizable to the consumer. When I worked with Jeremy his glass pours included only rare varietals. People found it pretentious at times, but it came from a place of really caring for the future of wine.

Do you think there are any misconceptions about Georgian wine, specifically about making wine in a qvevri?

I do think there are misconceptions about Georgian wine. I’ve had friends go to wine shops and see a wine from Georgia, and immediately assume it was made in an authentic method. There are many wines out there that are the industrial stuff we talk about in our film, which are mass-produced for the Russian market. For enthusiasts that are trying to get into wine, I encourage you to look at the back of the labels and consider the importer. Is it an artisan importer with good taste, or a large company with a sloppy portfolio of wines?

How does the wine culture you experienced in Georgia compare to other winemaking cultures you might be familiar with?

The wine culture in Georgia is unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Jeremy has worked wine harvests all over the world, and he feels the same. Winemaking is about life, and community, and culture. It’s not about money – it’s a way to preserve their lifestyle, song and traditions.

Did filming this documentary make you think differently about the wine industry in any way?

My experience in Georgia dramatically affected the way I see the wine industry. Preserving species and traditions is much more important to me than finding a wine that was given a high ranking on some point system. Ranking wines in that way directly harms small artisan farmers who are seeking to keep a diverse ecosystem and champion rare species.

When a consumer walks into a bar and orders a Cabernet, because that’s the only grape variety they know, it convinces bar owners to buy those common grapes. It’s harder to sell the unknown grape varieties from small vineyards. I hope that my films will be a way to share the stories of the unknown farmers and help the consumer feel comfortable to walk into a bar and try something they’re not familiar with.

Has this documentary inspired any future projects related to Georgian wine?

Filming this documentary led to Jeremy and I starting to make wine in Georgia – currently just for ourselves and our friends, but we would like to make wine to sell someday. It was a happenstance that we were not expecting. Our film became very personal for us, and although we’re not exactly sure our future with Georgian wine, it will always be close to our hearts.

You can rent or buy “Our Blood Is Wine” on Google Play or iTunes. A DVD of the film is also available for purchase on Amazon.

Published on July 02, 2018

Related stories

August 2, 2013

ShanghaiShanghai’s farm country is closer than most residents imagine, especially when surrounded by the city’s seemingly endless forest of skyscrapers. But just beyond the spires is a huge, green oasis: Chongming. Somewhat smaller than Hawaii’s Kauai, this island at the mouth of the Yangtze River grows much of the municipality’s food supply. The government is…

September 13, 2013

Mexico CityMexicans can mark their calendars by what they’re eating: moles for weddings, pan de muerto for Day of the Dead, lomo and codfish for Christmas and chiles en nogada for Independence Day. Every September 15 and 16 Mexicans gather together to celebrate their independence from Spanish rule. This movement started in the city of Dolores…

February 8, 2018

LisbonLisbon’s communities from Portugal’s former colonies provide the strongest link to the country’s past, when it was the hub of a trading empire that connected Macau in the east to Rio de Janeiro in the west. Though integral elements of Lisbon life, these communities can sometimes be an invisible presence in their adopted land, pushed…