On a narrow and, until recently, slightly forgotten street in Lisbon’s city center, a simple Cape Verdean eatery is holding its own. As one of the few tascas serving up African dishes in this part of town, Tambarina, with its dozen tables and keyboard and mics set up in the corner, bears testimony to this urban quarter’s historical connections to the people of Africa’s northwestern archipelago.

Rua Poço dos Negros – a street with an ambiguous name possibly relating to the dumping of slaves’ bodies here centuries ago – is on the border of what until two decades ago was known as “the triangle,” an area extending to São Bento and which in the 1970s became home to a new group of migrant Cape Verdeans. The triangle saw one of the few waves of substantial migration from the colonized islands to the metropolis of the former empire and is nowadays a mix of old multi-family houses – once belonging to the working classes – and new condominiums. Only a few members of the Cape Verdean community remain here; the majority of them now live in the city’s peripheral zones such as Amadora, Oeiras and Portela.

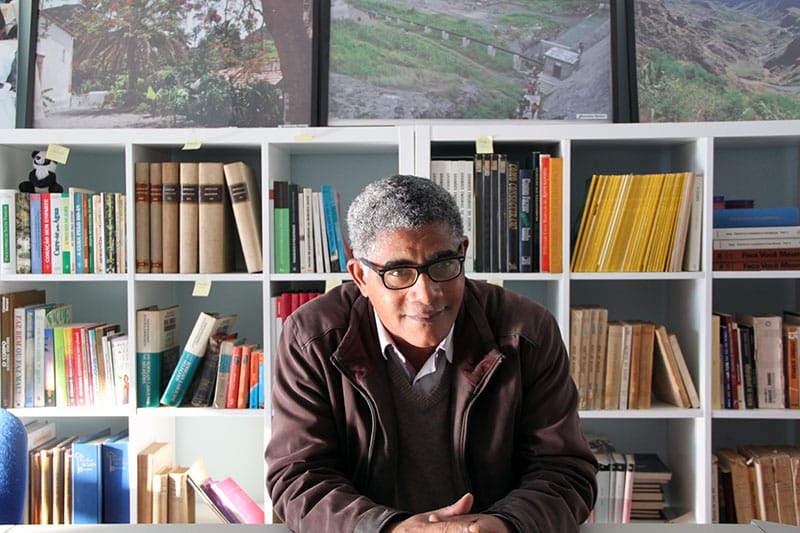

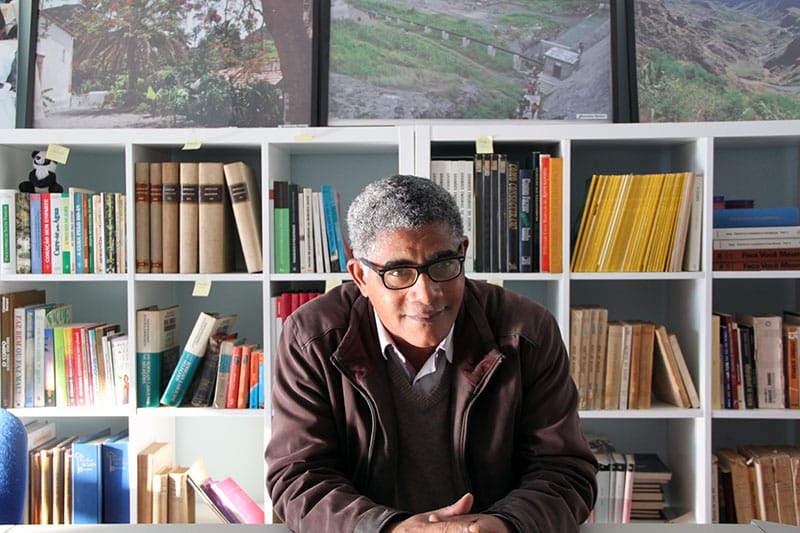

Domingos de Brito, owner of Tambarina, is one of the few who stayed. Like many others at the time, he arrived from the island of Santiago in 1971 at age 18 to work in construction. His roots are solid in the neighborhood, where he also ran a small enterprise exporting products (including food and clothing) to Cape Verde. Domingos opened the restaurant in 2011 and had to contend with the pressures of prejudice from neighbors and even the police. “When I opened it was a bit complicated; for an African it is hard to progress in Portugal due to discrimination,” he says. “But now, as I know everyone in the neighborhood, everything is fluid.” In this sense, the name is spot on: Tambarina is a tree that resists difficult conditions, especially drought – a periodic calamity in Cape Verde.

Domingos de Brito, owner of Tambarina, is one of the few who stayed. Like many others at the time, he arrived from the island of Santiago in 1971 at age 18 to work in construction. His roots are solid in the neighborhood, where he also ran a small enterprise exporting products (including food and clothing) to Cape Verde. Domingos opened the restaurant in 2011 and had to contend with the pressures of prejudice from neighbors and even the police. “When I opened it was a bit complicated; for an African it is hard to progress in Portugal due to discrimination,” he says. “But now, as I know everyone in the neighborhood, everything is fluid.” In this sense, the name is spot on: Tambarina is a tree that resists difficult conditions, especially drought – a periodic calamity in Cape Verde.

From the start, Tambarina has served up particularly tasty dishes thanks to Domingo’s already extensive culinary experience – as the last of seven brothers, he helped his mother in the kitchen from an early age.

The star dish here is cachupa: the pride of Cape Verdean gastronomy, this slow-cooked stew is made mainly of hominy, beans, cassava, sweet potato and fish or meat (sausage, beef, goat or chicken). In Cape Verde, the dish comes in many forms. At Tambarina, Domingo makes meat, tuna and even vegetarian versions. “The best thing for breakfast is cachupa refogada, re-frying leftovers with eggs and good quality pork sausage [linguiça].” The irony, he says, is that cachupa pobre – the modest version made only with fish –is a far superior dish to cachupa rica – which uses several kinds of meat and is expensive in the archipelago. The key, he says, is that the onions are sautéed in lard.

Cachupa is a dish with 500 years of history in Cape Verde and symbolizes the planting of corn and all the practices, techniques and accumulation of knowledge related to it. The ritual of its preparation evokes a sense of belonging and hospitality. More than any other dish, cachupa reveals an authentic expression of Cape Verdean identity.

Some etymologists relate the term “cachupa” to the Spanish cachupina, which refers to the gathering of people around music – a context that could be confirmed by the omnipresence of live music in Cape Verdean restaurants. Tambarina hosts mini-concerts from Thursdays to Sundays: batuque, funaná, colá, coladeira or morna musical styles blare from the speakers, transforming the restaurant into a party after dinner. It’s at this moment of the evening where Domingos usually goes to drag chef Augusta out of the kitchen to dance. “Music from Cape Verde is very sought after. All the genres have especially good rhythms and are lively; if you feel a bit sad, you listen to funaná, and you forget everything!”

Apart from the cachupa, which sings with flavor, Tambarina also specializes in chicken cooked with beer, grilled fish, tuna belly, veal with cassava and delicious corn pastries. All of these can be washed down with Cape Verdean grog (also grogue in Creole), which is made of a rum distilled from sugar cane from Santo Antão and Santiago islands. Like many of the ingredients that ended up in the archipelago, the abundance of sugar cane in Cape Verde was a consequence of colonization and the slave trade. In typical experimental style, Domingos also makes his own homemade punch, a recipe learned from his father: grog, sugarcane honey (“Not sugar!” he insists), lemon and a secret ingredient he won’t reveal. Whatever it is, it certainly goes well with the music.

Rua do Poço dos Negros 94, São Bento

Tel. +351 21 395 1111

Hours: 9am-2am

April 22, 2019 Southern Comfort

April 22, 2019 Southern Comfort

Sold for one or two euros, the spritz, which at its most basic is a combination of […] Posted in Naples March 18, 2020 Coronavirus Diary

March 18, 2020 Coronavirus Diary

I didn’t take the coronavirus seriously at first. In fact, its severity didn’t hit me […] Posted in Istanbul February 15, 2020 Hadramot Yemen

February 15, 2020 Hadramot Yemen

Istanbul's conservative Fatih district has perhaps the highest concentration of Syrian […] Posted in Istanbul

Published on May 13, 2022

Go Deeper

- Learn more about the history of the Cape Verdean community in Lisbon

- Cape Verdeans, particularly those from the island of Santiago, form one of the biggest migrant communities in Portugal. Because of the cyclical drought that afflicts the 10 volcanic islands making up this archipelago, the country’s sense of homeland coexists with the idea of movement, with Cape Verde recognized by many as an essentially diasporic nation.

Until the 1920s, Cape Verdeans in Portugal were primarily students, merchants or public servants of the empire. The flow increased substantially in the 1960s, due to drought in the Sahel area as well as the demand for construction workers in the empire’s capital. Migrants arriving in Lisbon in the 60s and 70s were almost solely men working in civil construction and at the Lisnave naval shipyard, with the capital’s first metro line, major new roads and utility infrastructure depending on their labor. In the 1980s, Cape Verdean women reached the capital to join their partners; most of them would sell fish in the streets or work as cleaners.

Until 1980, it wasn’t uncommon to find Cape Verdean families living in central – now upmarket – neighborhoods like Campo de Ourique, Estrela and São Bento. The majority of workers, however, lived close to construction sites in self-built peripheral communities that in the 1990s became large-scale housing estates. These urban areas were, and often still are, characterized by racial segregation and social exclusion.

Nowadays the Cape Verdean community in Lisbon is fragmented according to level of integration into Portuguese society. As well as improving quality of life for many, social disintegration, thorny housing issues and problems of paperwork and statistics (some Cape Verdeans have no papers, or conversely, have Portuguese nationality, making it hard to study their marginal conditions) means there is much invisibility surrounding this long-standing migrant community.

- Learn more about Cape Verdean cultural spots in Lisbon

- On the last floor of a high building in Marquês de Pombal – Lisbon’s financial and commercial area – is the headquarters of the Associação Cabo Verde, the oldest of its kind in the capital. Its unexpected location aside, it draws many from the community who need support with issues relating to law and integration issues and acts as a central meeting point for all types, including academics. As well as organizing events focusing on post-colonial Cape Verde and its diaspora, the association also hosts regular festive lunches (almoço dancantes), with live music on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

Dr. José Luis Hopffer Almada, the association’s vice president, explained to CB that this multi-roomed space was once a casa do estudante do imperio (house of the students of the empire), an institution that, despite being a tool of the Estado Novo regime, was an important venue in terms of raising awareness about independence (which Cape Verde gained from Portugal in 1975, one year after the Carnation Revolution). The association has since developed different projects over the decades, such as bilingual alphabetization, support for other Cape Verdean associations at the neighborhood level and development as a multi-faceted cultural center.

Nowadays, its raison d’être is to celebrate music and food, with its restaurant open to Cape Verdeans and their friends nearly evert day (ultimately, everybody is welcome, Dr. Hopffer says). The space, decorated with paintings and afforded a stunning view thanks to its location on the eighth floor, is often crowded, where eating cachupa to the rapid and melodic sounds of batuqueira comes standard.

Related stories

April 22, 2019

NaplesSold for one or two euros, the spritz, which at its most basic is a combination of bittersweet liqueur, sparkling wine and seltzer, has been dubbed “the champagne of the poor” – no wonder it has been the king of cocktails in Naples for at least a decade. Aperitif time – often starring a cool spritz…

March 18, 2020

IstanbulI didn’t take the coronavirus seriously at first. In fact, its severity didn’t hit me until a few days ago. Earlier this month I was in Berlin, visiting my brother. The city’s tourism fair was abruptly canceled as a result of the virus, but we weren’t worried. We went out at night, eating and drinking…

February 15, 2020

IstanbulIstanbul's conservative Fatih district has perhaps the highest concentration of Syrian refugees in the city, and the tree-lined Akşemsettin Street boasts a staggering number of Syrian eateries, from spacious sit-down affairs with full menus to hole-in-the-wall, standing-room-only kiosks slinging shawarma, fried chicken, and falafel. Having popped up rapidly amid the waves of Syrians fleeing the…