Update: Gastronomika’s community kitchen is not at SALT Beyoğlu anymore.

Who says there’s no such thing as a free lunch? In fact, over at Gastronomika, a new Istanbul culinary project, the food is served not only free of charge but also with an intriguing – and ambitious – backstory.

As Gastronomika’s founders describe it, the project is “an open-source, long-term, community project” whose goal is nothing less than domestic and international “rebranding” of traditional Anatolian cuisine. We recently met up with Engin Önder and Semi Hakim, the project’s creators, in Gastronomika’s community kitchen at SALT Beyoğlu to find out more. SALT is an eclectic cultural institution that – along with Gastronomika’s community kitchen – hosts art exhibits, a rooftop garden affiliated with the local Slow Food chapter and the Robinson Crusoe bookstore, an Istanbul institution that was recently evicted from its nearby longtime home on the bustling pedestrian thoroughfare İstiklal Caddesi.

Two and a half years ago, a cohort of designers, food researchers, anthropologists and architects started talking about creating a far-reaching program to, as Önder puts it, “re-identify, reposition and rebrand” Anatolian cuisine. Eight months ago, the project came to life when SALT handed over the keys to the building’s ground-floor kitchen, giving the project a home.

Önder, Hakim and friends saw what they believed was a problem with how and what people were eating in Istanbul, with younger generations especially spending their money at fast-food chains instead of appreciating their homegrown cuisine. Local eaters, the two say, are more familiar with Western-style cheesecake than, for example, the traditional Anatolian cheese and semolina dessert known as höşmerim. “Höşmerim is presented horribly, in small, flimsy yogurt containers,” says Hakim, who is a professional chef. “Would you take a picture of neon-yellow höşmerim and put it online? No,” argues Önder, a social media activist who coordinates a citizen journalism network. So the team kept asking themselves, How do we make höşmerim as cool as cheesecake? How do we make Anatolian cuisine, with all its nuance and deliciousness, attractive to a generation inundated with food porn images in ads and on their friends’ Instagram feeds? If that wasn’t enough, Gastronomika also wants to teach İstanbullus about seasonality and to reconnect consumers with producers. These guys are full of energy and ambition, so they also want to fix Anatolian cuisine’s image abroad, where, they believe, it is being “misrepresented.”

To meet these goals, they decided to create an open online database that will be filled over the next seven years with recipes from extensive research tours in Turkey, months-long kitchen experiments and public contributions. Three teams – kitchen, design and research – created two “curriculums,” one focusing on techniques and the other on ingredients. For example, the first chapter of the first curriculum is about how to cook pulses, legumes and grains. For three months, the research team has met every Wednesday to discuss new findings about recipes and the kitchen team has conducted experiments. They upload recipes onto the database for people to comment on and add to. There is also a map interface, so the public can find out where recipes come from and learn about similarities between regions.

Although their project was initially met with criticism, Gastronomika is quickly creating a tight-knit community of young opinion leaders who want to learn about Anatolian food. Everything in the Gastronomika kitchen – pots, spices, meats, oils, vegetables – is donated by friends. Every ingredient has a story and a connection to a place that the team records in its online database. Chefs and friends prepare weekly feasts that are free to whomever visits the kitchen (making it worthwhile to keep up with their calendar or just drop in). One afternoon we watched culinary students from Istanbul’s MSA Culinary Arts Academy prep a three-course feast of lakerda (pickled bonito) with Çanakkale tomatoes, Ottoman palace artichoke pilav, and calf’s liver stuffed with fava purée. On another occasion, the owner of Fıccın, a nearby classic lunch spot, came by to make some of her signature dishes from the Caucasus region. Offering free, high-quality food prepared with love is a cunning tactic to pull eaters back to Anatolian cuisine.

“People always have something to say about food,” says Önder. “First we want them to develop a preference for Anatolian cuisine, and then we want to turn them into cooks.” To turn eaters into cooks, members of the Gastronomika team go to farmers markets every weekend, where they let shoppers know what is in season and how they can cook those ingredients. “For example, we want to encourage people to use kaymak (clotted buffalo cream). Then we ask them to find out which region has better kaymak. Next, we ask them when is the best season to consume kaymak. These are baby steps,” explains Hakim. They hope that connecting people to the seasons and food producers will make eaters more conscious about their environment, geography and culture.

We are excited to check out Gastronomika’s upcoming “Hacking the Modern Kitchen” installation for the Istanbul Design Biennial, which runs November 1 to December 18 at Galata Greek Primary School. The team has been traveling through Anatolia this summer collecting data for the installation, which will show city residents how to convert their kitchens into Anatolian kitchens, with spaces dedicated to food preservation and gardening. Refrigerators are not part of the blueprint.

May 15, 2017 Biscoito Globo

May 15, 2017 Biscoito Globo

Asking cariocas if they remember their first Biscoito Globo, the ubiquitous, crunchy […] Posted in Rio November 9, 2015 CB Book Club

November 9, 2015 CB Book Club

Editor’s note: In the latest installment in our Book Club series, we spoke to Jordana […] Posted in Mexico City January 5, 2023 Confeitaria Nacional

January 5, 2023 Confeitaria Nacional

In a nation with so many baking and confectionary traditions, it’s surprising that one […] Posted in Lisbon

Published on September 04, 2014

Related stories

May 15, 2017

Rio | By Danielle Renwick

RioAsking cariocas if they remember their first Biscoito Globo, the ubiquitous, crunchy beach snack, is like asking anyone who teethed in the United States if they remember trying Cheerios for the first time. Globo biscuits and sweet iced mate are to Rio's beaches what hot dogs and beer are to American baseball stadiums. Calls of “Ó…

November 9, 2015

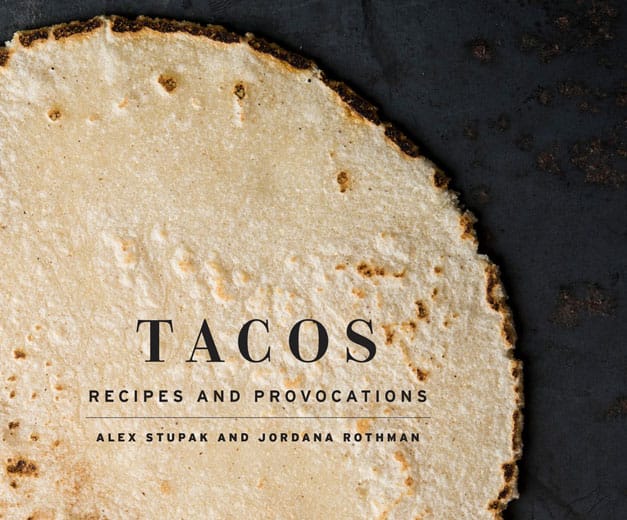

Mexico City | By Culinary Backstreets

Mexico CityEditor’s note: In the latest installment in our Book Club series, we spoke to Jordana Rothman and chef Alex Stupak, co-authors of Tacos: Recipes and Provocations (Clarkson Potter, October 2015). How did this book come to be? We met right before Empellón Taqueria opened in 2011 and instantly felt that we were simpatico in the…

January 5, 2023

LisbonIn a nation with so many baking and confectionary traditions, it’s surprising that one of the most popular cakes – the bolo-rei – was imported from another country (a sweet tooth does not discriminate, apparently). Translated as “king cake,” the bolo-rei was brought to Portugal from Toulouse, France, by one of the oldest bakeries in…