Two-and-a-half kilometers of curves and narrow alleys at 150 meters above sea level. Breathtaking views overlooking the sea. A coast dominated by the blue of the sky and dotted with arabesque domes. All around is the unmistakable perfume of the sfusato amalfitano – the Amalfi lemon.

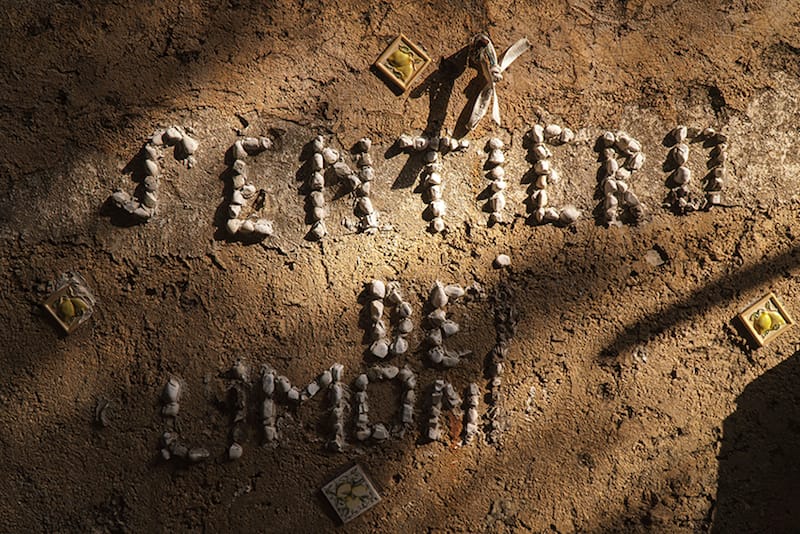

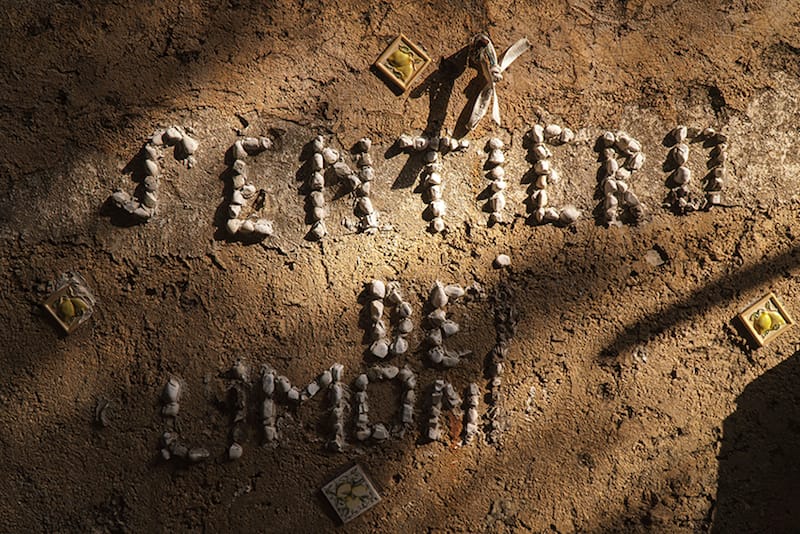

Backpack on shoulders and comfortable shoes on our feet, we are on the Sentiero dei Limoni, the Path of the Lemons. This ancient two-kilometer road connects the sister towns of Minori and Maiori on the Amalfi Coast. Wild, daring and romantic, this coastline and its terraces suspended over the sea has a heritage of ancient art and architecture that make it one of the most famous places in the world. And that includes its citrus.

The Amalfi lemon is bright and fragrant, known for its characteristic tapered shape, thick skin rich in essential oils, low seed count and above-average acidity – making it perfect for pastry and cooking (and not just the endless glasses of lemonade we are offered while on the Sentiero dei Limoni).

Ahead of us on the trail is activist, environmental hiker and filmmaker Francesco Damiano, who goes by Frank. Dressed head-to-toe in khaki, he’s also called the Neapolitan Indiana Jones. It’s an apt nickname, not just for his get-up but because of his commitment to raising awareness on the precarious condition of the Path of the Lemons.

Frank used to work at an import and export company, but four years ago he quit his job to explore this corner of paradise. While doing so, he heard the cry of alarm launched by the pro loco (grass-roots civic association) of Minori. They feared for the extinction of the sfusato on a particular patch of the Amalfi Coast, the village of Torre, where barely 100 people currently live, almost all of them over 70 years old. So, Frank has brought many through – both foreign tourists and Campania locals alike – to see, smell and hear about the role of Torre in the production of the Amalfi citrus, as they walk along the Path of the Lemons.

To the Village of Torre

We ascend the staircase leading to the Sanctuary of Santa Maria, and from above we admire the Mezzacapo Palace, now home to the Maiori Town Hall. An 18th-century garden, designed in the shape of a Maltese cross, buzzes with life. We climb another 350 steps, walk down a flat pathway, start descending, only to go up once more. Up and down we climb, and at one point the Bay of Maiori stretches below us. It is the longest stretch of beach on the coast.

A few more steps and Frank calls out to two friends, Alfonso and Gimondo. They are both porters by profession – Alfonso working his two legs and Gimondo, a donkey, on four. Together, they transport luggage, gas cylinders, construction materials and other goods for locals and tourists, as there are no cars out here on the Sentiero dei Limoni.

We see the first lemon groves ahead in the distance. In May, when we made our journey, the scent of blossoms is intoxicating, and our nostrils are filled with the sweet and pungent fragrance. A spectacular panorama is before us, composed of low-roofed pergolas typical of the coast. Unlike in the nearby Sorrento, where the lemon trees grow high, lemons are cultivated atop these arching pergolas. Here, the trees do not grow tall as they do elsewhere, because the flowers would be hostage to the sea wind.

Since all of the plant is able to lap the sun’s rays – instead of those branches that would normally be highest on the tree, the fruits ripen at the same time. It’s technical, parochial wisdom at work. What may have previously been an ornamental plant is now, with the discovery of its organoleptic properties, an emblem of Campania as well as the nation’s fruit production.

Lemon groves have been present on the Amalfi Coast since ancient times. In the course of their expansion and conquests, the Arabs introduced the lemon to Spain and Sicily, and eventually it made its way to Campania. But it was the discovery of the lemon’s use against scurvy, rich as it is in Vitamin C, that bolstered the spread of its cultivation here. In the 11th century, the Amalfi Republic – home to great seafarers – decreed that local ships must be stocked with the fruit. From 1400-1800, the demand for Amalfi lemons was very high, including from other countries, especially in Northern Europe.

As we follow Frank, he spies the garden of Uncle Tonino, an 85-year-old. The man does not stop for even a day. In these quiet villages, there are typically no more young people to pass on the baton, and it is up to those who have lived on the land for generations to continue rolling up their sleeves. Uncle Tonino, however, has Giovanni Ruocco, who represents the fourth generation of small agricultural entrepreneurs in his family.

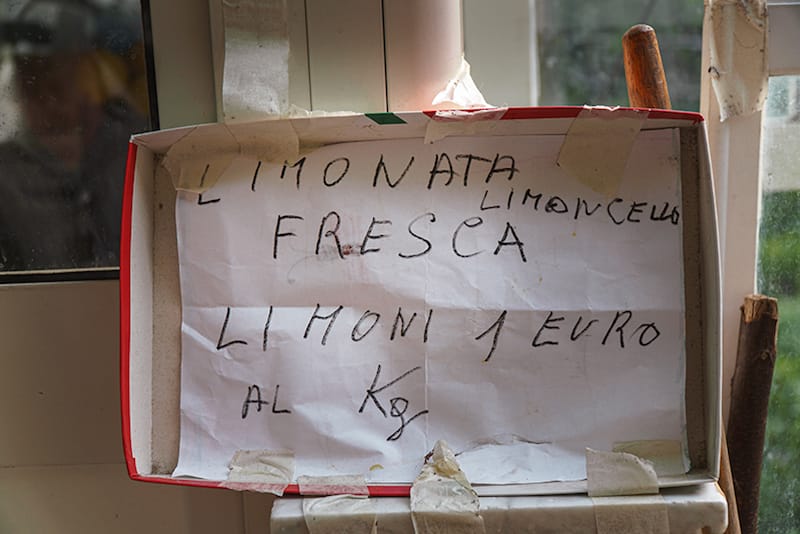

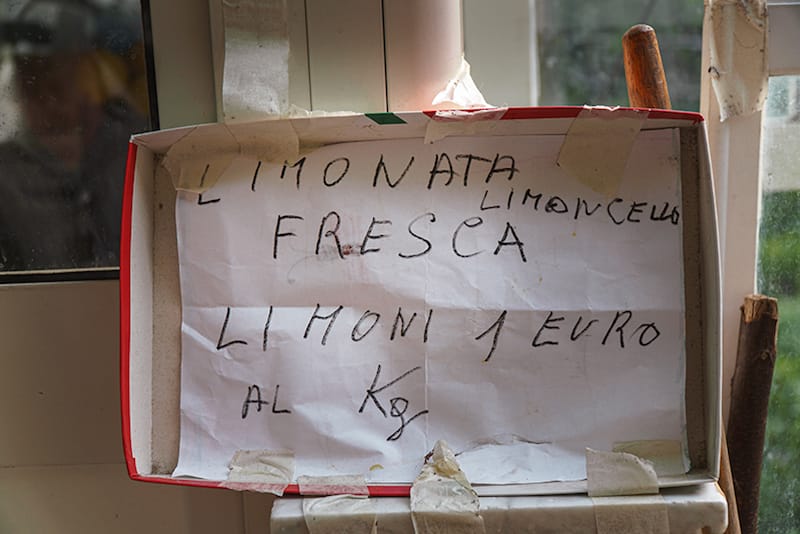

“Sfusato doesn’t just produce juice,” Giovanni tells us, as he offers glasses of fresh lemonade to hikers passing by on the path “They can become limoncelli, cosmetic products, soaps, jams, pastries. Compared to Calabrian, Sicilian, Spanish and Argentine lemons, these lemons are a whole other story. The fruits are just sweeter,” he explains. Hikers exchange a couple of euro for his kilometer-zero produce and products – which includes a lemon salad aperitif.

“I am 34 years old, and here in the Torre village I am the only one of this age to take care of a lemon grove. We have 500 trees on two properties, but a large part of the Path of Lemons is in danger of extinction due to advanced age of the villagers and flight to the north and abroad. I returned just in time, but you can’t live on just the lemon harvest. We are confident in the future tourism will have for this place,” he says.

According to the official outlet of the Campania Region, many of the lemon crops in the area are slowly being abandoned, with those in the most difficult-to-reach places left unharvested. This is partly due to the small number of workers who can access the terraced groves, as well as the labor-intensive process of transporting the lemons.

A few meters further on, we catch a glimpse of a cheerful granny, who we are told is a very special person. Zia Maria is 94, and the last formichella, lemon harvesters. She and the women of her generation have given so much to this territory. Tireless workers, they walked the path with a basket of lemons on their heads or hanging on their backs, transporting them from their gardens to the sea on journeys that lasted up to two hours. There are poems and paintings dedicated to their pilgrimage, heroines of the Amalfi Coast.

“In this huge reserve of wonders,” Frank says, “I cannot omit the humans, those who have shaped the territories, brought them alive, just like Zia Maria. … She has had a life full of sacrifice and struggle, but she always gives a smile, despite everything.” Here are stories, scents and colors that can only be experienced in the village of Torre.

From the Path and into the Kitchen

It’s no surprise that the sfusato is the main ingredient at all of the local pastry shops in Amalfi, in desserts like babà al limoncello, cakes and profiteroles. But its intense aroma, thick skin, and juicy and semi-sweet pulp have made the fruit, which has Protected Geographic Origin (PGI) status, widely popular. It is even served plain, as a simple appetizer. Common in the region is its use as a condiment on fish, seafood and meat. Some of the area’s best chefs have made it a gastronomical attraction at their restaurants, and even cafes serve drinks like lemon coffee and, of course, limoncello.

In Amalfi, the Pansa pastry shop in Piazza Duomo is home to the “Delizia,” which was created by the Sorrentine pastry chef Carmine Marzuillo in 1978. It is a cake stuffed and covered with lemon cream, and has a base of sponge cake soaked in a limoncello syrup.

“Plunging your spoon into our delight is like leafing through the pages of a book that you have read many times and that you wish would never end,” the pastry shop writes on a recent Facebook post. The history of this company is intertwined with the vicissitudes of a family that has proudly guided it for five generations. Founded in 1830 by Andrea Pansa, the shop’s charm is in its unchanged appearance, full of 19th-century furniture and gilded mirrors. One of the oldest confectionaries in Amalfi, in February 2001, Pansa received prestigious recognition as a “Historical Place of Italy.”

A few kilometers away, in Minori’s Via Roma, the famous pastry chef Sal De Riso has invented another dessert inspired by the local lemon. The Sfusato della Costiera is a sponge cake filled with Italian Chantilly cream, and is best paired with Moscato d’Asti. Another good pairing is with an artisanal liquor made from carefully selected sfusato, called “Paesaggi.”

And it doesn’t end there. On the Maiori seafront, the Sfusato Amalfitano ice cream cart hawks its citrus creams and sorbets, and over in Salerno, a sfusato mousse is stuffed into a shortcrust pastry. In Nola, the well-known Casa Caldarelli bar serves a dessert with sfusato ganache, very fragrant and irresistible. And then there is the lemon pizza, dubbed the “Positano” and topped with sfusato shavings. This local rind has made its way into other savory dishes, like pastas, up and down the coast.

And championing the legacy of this legendary fruit is Frank. “Traveling is beautiful,” he says, “but sometimes, what we are looking for is at our feet and we do not realize it.” As we look out at the azure sea, the smell of nearby lemons drifts toward us. “My work is an excuse to shed light on and raise awareness of our forgotten – or worse, ignored – cultural and artistic heritage. I talk about the unknown places, traditions and authentic characters of my land. It both satisfies my curiosity and fills me with gratitude. In a nutshell, it is not a job but a mission.”

This article was originally published on April 14, 2022.

July 28, 2022 Da Maria: Spanish Quarter Secret

July 28, 2022 Da Maria: Spanish Quarter Secret

Naples’s Quartieri Spagnoli, the "Spanish Quarters,” are a part of the city with a long […] Posted in Naples April 28, 2022 CB On the Road

April 28, 2022 CB On the Road

In the tiny Italian town of Cuccaro Vetere, some 150 kilometers south of Naples, […] Posted in Naples April 21, 2022 The Florist Bar

April 21, 2022 The Florist Bar

There are flowers all around us. Seeds and plants are scattered here and there. Herbs […] Posted in Naples

Giuseppe Delle Cave and Gaetano MassaGaetano Massa

Published on May 08, 2024

Related stories

July 28, 2022

NaplesNaples’s Quartieri Spagnoli, the "Spanish Quarters,” are a part of the city with a long and tumultuous history. Founded in 1500, the Quartieri Spagnoli were created by Don Pedro De Toledo to accommodate the Spanish soldiers who were residing or passing through Naples. With the arrival of the soldiers, the network of narrow streets became…

April 28, 2022

Naples | By Alessio Paduano

NaplesIn the tiny Italian town of Cuccaro Vetere, some 150 kilometers south of Naples, villagers are surrounded by nature and an incredible variety of local fruits. The town, which is in Campania’s province of Salerno, has just over 500 inhabitants, and – even more than their nature’s bounty – these residents are known for one…

April 21, 2022

NaplesThere are flowers all around us. Seeds and plants are scattered here and there. Herbs and fresh fruits rest in wicker and reed baskets. Sitting amongst all this glory is Stefania Salvetti, who is telling us about Paradisiello, where she lives. Meaning “Little Paradise” in Italian, Paradisiello is where Stefania has a home with 2,000…