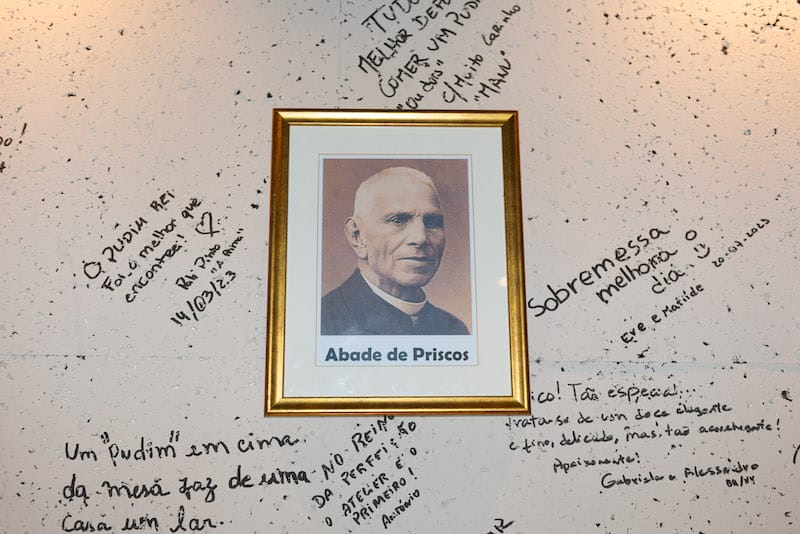

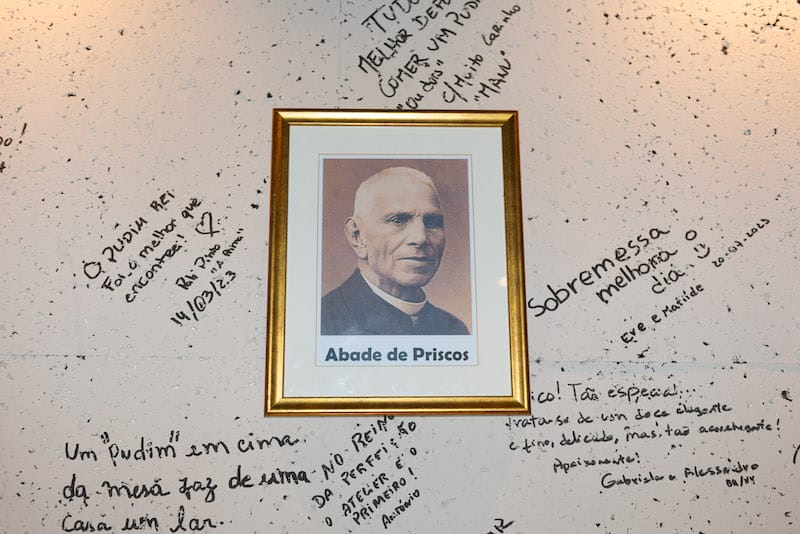

“It’s the king of Portuguese gastronomy,” declares Miguel Oliveira. He’s describing pudim Abade de Priscos, one of Portugal’s most infamous desserts, and the dish that is the specialty of his Lisbon sweets shop.

Allegedly invented by the eponymous abbot in the 19th century (pudim is a term that refers to a variety of steamed desserts in Portugal), the dish unites a staggering 15 egg yolks, sugar, pork fat, port wine and aromatics in the form of a gleaming, golden ring. It’s easily the most over-the-top dessert in a country of already over-the-top desserts, and is the dish that has captivated Miguel more than any other.

“I couldn’t believe it was possible to make a dessert like this from just egg yolks and a few other ingredients,” Miguel tells us of his first encounter with pudim Abade de Priscos. “It was a challenge for me.”

We’re at Atelier Pudim Rei, Miguel’s dual shopfront and kitchen in Lisbon’s Marquês de Pombal neighborhood. He makes a handful of other desserts out of the tiny space, but the star – as well as the recipient of several prizes and much praise and recognition – is his take on pudim Abade de Priscos.

“We call this kitchen a laboratory,” says Miguel, as he escorts us inside the narrow kitchen. “We’re always testing things in here.”

Indeed, it took Miguel six months of trial and error before he arrived at a recipe for the pudim that he felt confident enough to sell. And although he often employs the first-person plural, Miguel did all this research alone, and continues to make every single pudim on his own, without any assistance.

Miguel has agreed to show us how pudim Abade de Priscos is made, and explains that the dish begins with a syrup. But even this seemingly simple step is fraught with complexity.

“The minerality of the water is important,” Miguel tells us, one of many discoveries over those months of testing. In a saucepan, he combines water, white sugar, strips of lemon zest, sticks of real cinnamon and slices of cured fat from chestnut-fed Bísaro pigs in Portugal’s far north. (“This is the sexiest ingredient,” he says of the latter.) As the mix simmers, he takes in the aroma, observes the bubbles and occasionally dips his fingers in the syrup, scrutinizing the strands that form. At no point in this process does he use a thermometer. The disparate ingredients fill the space with a pleasant, although hard-to-pin-down aroma. When the syrup is deemed ready, he pulls the saucepan from the heat.

“The difference between a good pudim and a bad pudim is ten seconds,” he tells us – yet another hard-earned lesson.

Next, he places 15 egg yolks in a wide sieve. With a small knife, he gently slices through the orange sacs, an effort to separate the membranes, which could potentially give the final product an inconsistent texture. To the strained yolks, he adds a shot of aged tawny port, and whisks the ingredients together. Finished with this task, he touches the syrup saucepan with the back of his hand: “If I added the syrup to the eggs now, they would experience thermic shock and not come out right.”

When the syrup has cooled sufficiently, he combines it and the egg yolk mixture, straining the thick liquid into an aluminum ring mold lined with caramel. After removing any bubbles from the surface of the liquid with a spoon, he tops the mold with a layer of foil – “water is the enemy of this pudim” – then a lid, and the dish is steamed for about an hour in a combi oven.

While the dessert cooks, Miguel offers us a taste of an individual serving of Abade de Priscos, sold in small glass jars. He overturns one on a plate, drizzling the golden puck with the residual syrup. We ask him to describe his ideal version of the dessert.

“It starts with the appearance,” he explains. “A good pudim should have a uniform appearance. It should have some transparency” – he pulls out a flashlight to demonstrate this – “with no visible bubbles. No flavor should be stronger than any other. For example, the pork fat should not stand out. There should be balance.”

The result is transcendent, though admittedly a bit challenging, as pudim Abade de Priscos doesn’t necessarily match with many of our contemporary Western ideas of a dessert. It has a texture like a denser, more unctuous Jell-O. It’s admittedly sweet, but this is almost eclipsed by a deep richness. And the inclusion of pork fat throws many of us for a loop. Yet its various flavors, aromas and textures coalesce in a way that reminds us of the complexity of the aged fortified wine it includes.

As we take in this culinary masterpiece, Miguel shares a quote attributed to the Abade de Priscos, who allegedly said of the dessert, “‘It’s easy to make, but difficult to achieve.’”

Austin BushAustin Bush

Published on January 04, 2024

Related stories

May 27, 2024

PortoIt took four years for couple Yvonne Spresny and Morgan von Mantripp to turn an old dream into reality: opening a coffee shop where they could roast their beans from various parts of the world. From Wales and Germany, they ironically found the perfect place in a cozy space in the Bonfim neighborhood in Porto,…

April 9, 2024

PortoMore than a food staple, the rissol is also a symbol of the popular culture in Portugal, where locals eat it standing at counters, always paired with a cup of coffee – or a glass of tap beer from eleven o'clock onwards. Rissóis (plural) are half-moon-shaped savory pastries of peasant origins, and from grandmothers' houses…

March 25, 2024

LisbonThose pastry shops that seem to command just about every corner in Lisbon? They’re an important institution in the city, as well as an utterly delicious way to start the day. But the truth is, these days, the range of pastries sold in Lisbon is limited and many of those sweets are produced on an…