Turkey’s rich regional food culture reflects its diverse landscapes: seafood, olive oil and wild greens along the Aegean Sea; wheat- and meat-heavy dishes in the country’s heartland; corn, collards and anchovies on the rugged Black Sea coast.

But with climate change altering the environments that produced those ingredients, what will happen to the dishes they inspired? Will the way people in Turkey eat have to change too? And if so, how?

Those are the kinds of questions posed by CLIMAVORE: Seasons Made to Drift, a thought-provoking exhibition on display at Istanbul’s SALT Beyoğlu cultural center on İstiklal Caddesi until August 22. Five commissioned works by the London-based artist duo Cooking Sections (Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe), made in collaboration with SALT’s research team, delve into the history of food production in Turkey, consider its present state and envision its possible future.

Visitors are greeted on the ground floor by the piece “Weathered,” which transforms the entry hall’s columns into a forest-like installation of plant fossils, pollen samples, tree cores, and other evidence of environmental and climatic events over the centuries.

“Turkey experienced many harsh weather events before the invention of modern meteorology,” says Meriç Öner, director of research and programs at SALT. “So we had to go to various other types of records and look at all these different pieces together to see how weather affected both society and food production.”

The physical records are paired with historical texts – letters, newspaper articles, poems, travel diaries – documenting floods, droughts, heat waves, freezes and the crop failures, famines, and disease outbreaks that resulted from them. An 1895 account of a drought in Konya feels plucked from current headlines (though the farmers back then were worried about their harvests of opium, in addition to wheat). An except from a 1874 letter – “Cereals have become so expensive…that no one ever remembers having paid such high prices” – meanwhile evokes similar concerns about soaring inflation today.

“These events always existed, but we see them now occurring in a different rhythm,” Öner says. “Over the past 40 to 50 years, the [environmental] changes are coming at a rate that we can openly perceive in our lifetimes.”

Another Cooking Sections piece at SALT, “Unicum,” features a recorded dialogue in the Black Sea region’s traditional whistled language kuş dili (“language of the birds”) about how local fish populations are changing as a result of warming, pollution and other environmental factors. Mussels, eel, swordfish, rockfish and the treasured hamsi (anchovy) are becoming less abundant, while jellyfish, barracuda, pufferfish and pipefish are appearing in the Black Sea for the first time. Unrolled between two speakers playing the dialogue, a long, narrow thick-weave carpet is stitched with symbols representing some of the region’s new underwater inhabitants, as if imagining a future where they too might be part of a remembered past documented through folk crafts.

The spare visual presentation of this and other pieces in the exhibition contrasts with the in-depth research process that Cooking Sections and SALT carried out over nearly three years, delving into written sources in Ottoman, Armenian and other languages representing the diverse cultures that have shaped modern Turkey – and its food. The team also traveled to different locations around Turkey to learn about how different growing regions and their yields have been affected by the changing climate.

“In school we all learned the seven climactic regions of Turkey, and had to memorize what their weather was like and what they produced, but this information no longer matches reality,” Öner says. “Many hazelnut producers in the Black Sea, for example, have cut down their trees to grow kiwis, and the best hazelnuts are now coming from higher up in the rainier mountains, even though they are still associated with the coastal cities of Giresun and Ordu.”

“In school we all learned the seven climactic regions of Turkey, and had to memorize what their weather was like and what they produced, but this information no longer matches reality.”

The shifting fortunes of another famous local delicacy – Diyarbakır watermelons – are alluded to in a third piece of the CLIMAVORE exhibit, “Exhausted,” which examines the connections between human and agricultural fertility. Postcards, postage stamps and posters from the 1980s depict the famously prodigious fruit, which regularly topped 50 kilograms in size. The massive melons are traditionally grown in holes dug into the riverbed of the Tigris and fertilized with manure collected from dovecote towers, a replica of which was built for “Exhausted.” Only a scant few dovecotes remain in Diyarbakır, where they used to number nearly 300, and farmers say the declining use of this natural fertilizer has affected the fruit’s size and taste.

“The heavy use of nitrogen-based fertilizer [in modern agriculture] feeds the nation more quickly, but also depletes the soil,” Öner says.

These kinds of connections between food and ecology are at the heart of Cooking Sections’ research-based art practice, which often bleeds into activism. The duo’s current exhibition on salmon at Tate Britain, for example, prompted the art institution to remove farmed salmon from the menu at all of its food-service venues. And Cooking Sections’ broader, ongoing CLIMAVORE initiative, of which the SALT exhibition is a part, aims to propose “an adaptive form of eating” more suitable for our changing planet.

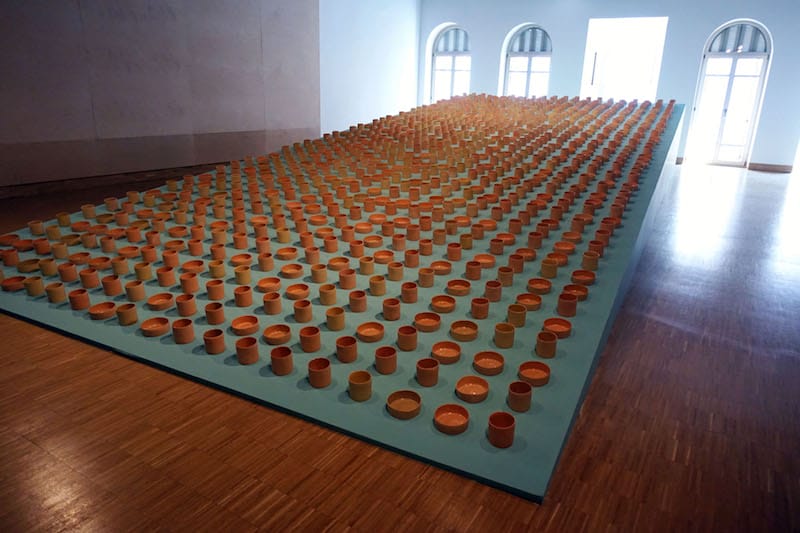

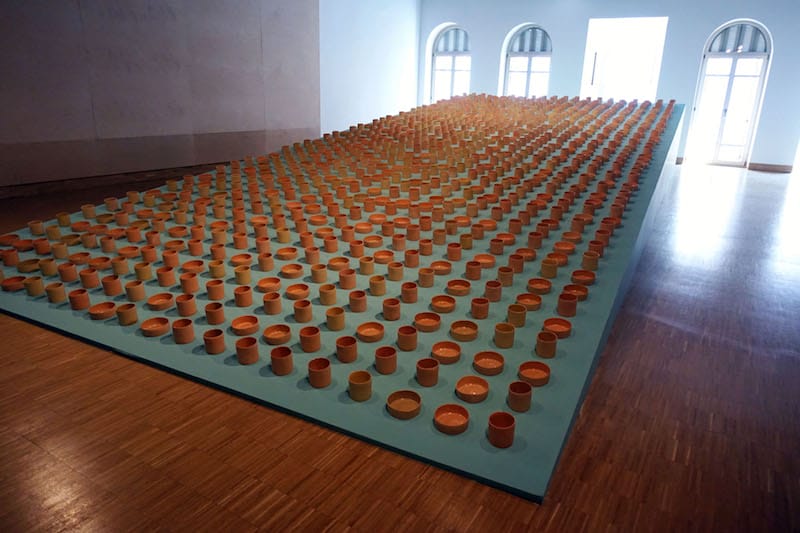

In Istanbul, that has meant imagining ways to help sustain the herding of manda (water buffalo) in the marginal lands on the edges of the city, which are continually being diminished by the spread of urbanization and large infrastructure projects like the new Istanbul Airport. For their piece “Lasting Pond,” Cooking Sections worked with potter and archaeologist Başak Gökalsın to make 1,000 pots for sütlaç (rice pudding) and yogurt – both especially delicious when made with fat-rich manda milk – from the clay in a buffalo wallow they had dug to help replace damaged natural wetlands. The installation of pots is on display at SALT, and some lucky visitors receive a coupon for a free sütlaç from a nearby shop still making the creamy dessert with buffalo milk.

Cooking Sections has also partnered with Istanbul culinary school Mutfak Sanatları Akademisi (MSA) to create dishes using buffalo milk as part of its curriculum, a collaboration on hold until the new school year due to Covid-related restrictions on in-person education. The duo will also work with MSA to develop new recipes using coastal vegetables and herbs in the place of farmed fish. The growing number of fish farms along the Aegean is the subject of their piece “Traces of Escapees,” which pairs projected footage of the confined fish with a voiceover narration about the environmental problems such facilities can cause.

“We’ve put all these fish farms along the Aegean, but this is also the most lush place for herbs,” says Öner. “Are we really making the most that we can of them, or just limiting ourselves to a few standard meze?”

The idea, then, is to work with ingredients that are closer to what the region naturally produces – an artistic statement that avid eaters can certainly get behind.

CLIMAVORE: Seasons Made to Drift is on display at Istanbul’s SALT Beyoğlu cultural center on İstiklal Caddesi until August 22.

April 20, 2023 The Perfect Spring Day

April 20, 2023 The Perfect Spring Day

Across Marseille, winter’s neon-yellow mimosas have given way to amandiers’ (almond […] Posted in Marseille April 25, 2022 Lider Pide

April 25, 2022 Lider Pide

Roaming the streets of Istanbul at 8:30 a.m. on a Sunday can be a surreal experience. […] Posted in Istanbul February 2, 2022 Meat Palaces

February 2, 2022 Meat Palaces

Ask anyone from the Eastern Turkish city of Bitlis where büryan kebabı comes from, and […] Posted in Istanbul

Published on June 22, 2021

Related stories

April 20, 2023

MarseilleAcross Marseille, winter’s neon-yellow mimosas have given way to amandiers’ (almond trees’) fragrant white and pink blooms. Here, the French adage, “en avril, ne te découvre pas d'un fil. En mai fais ce qu'il te plaît,” (in April, don't remove a stitch. In May, do as you wish,”) is oft quipped, for our springtime weather…

April 25, 2022

IstanbulRoaming the streets of Istanbul at 8:30 a.m. on a Sunday can be a surreal experience. The sun is shining, the seagulls are bellowing as they dip and dive – but the normally bustling streets are quiet. A few shops might be lifting their shutters, and cafés in younger neighborhoods may only just be putting…

February 2, 2022

Istanbul | By Erin O’Brien

IstanbulAsk anyone from the Eastern Turkish city of Bitlis where büryan kebabı comes from, and they’ll proudly tell you that the slow-cooked meat dish hails from none other than their hometown, near Lake Van. Pose the same question to folks from Siirt, just 100 km south, and they’ll insist anyone making it from a city…