We can't find the internet

Attempting to reconnect

Something went wrong!

Hang in there while we get back on track

New Orleans's culinary record

For a city of its size – tiny by contemporary American standards – New Orleans casts a very long shadow when it comes to things culinary. And when it comes to foodways and drinking culture, the city stands firm even as it playfully winks at you. It’s a series of living cultural stories that, like the hearty yet feather-light po’ boy, is well worth digging into.

Get the Full Story →

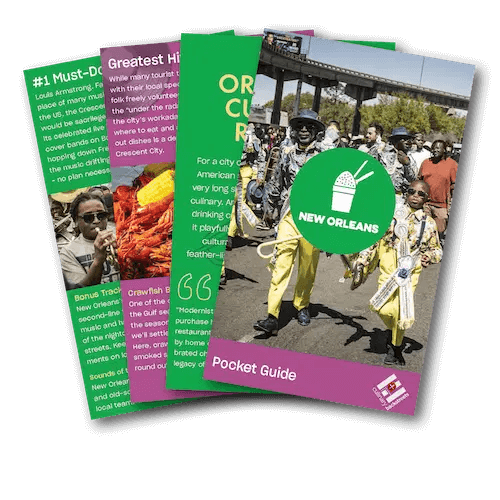

Get Your Free New Orleans Pocket Guide

Introducing our pocket-sized New Orleans guide — perfect for your next culinary adventure. Yours free when you sign up for our newsletter.

Get Your Free New Orleans Pocket Guide

Introducing our pocket-sized New Orleans guide — perfect for your next culinary adventure. Yours free when you sign up for our newsletter.

Visual Dispatches from the Frontlines of Local Eating

New Orleans Videos

Your Questions, Answered

New Orleans is a city in the state of Louisiana in the American South. It is located between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, near the Gulf of Mexico. It is the most populous city in the state. It was once the capital of French Louisiana before the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

New Orleans is famous for its gastronomical culture, night life, music, festivals and of course, Mardi Gras. Our most famous tourist attractions are the St. Charles Avenue Streetcar, St. Louis Cathedral, Jackson Square, Bourbon Street and Café du Monde, which are all within the Vieux Carre, the “Old City” or French Quarter. New Orleans is far more than this, however.

A number of neighborhoods are a tapestry of sights, sounds and tastes that are unlike anywhere else in the United States. Our Creole cuisine, represented in dishes like gumbo and crawfish etouffée, grits and grillades, po’ boys and muffulettas, and pho and banh mi, tell the history of the people who have made New Orleans home throughout its 300 plus years of existence. Our lush parks, such as Audubon Park and City Park, provide ample spaces for relaxation, reflection, and exercise. Live music is a way of life in New Orleans. We are the birthplace of both Jazz and Rock and Roll. Live Music can be heard throughout the city, from the Maple Leaf Bar or Tipitina’s uptown, to Frenchmen Street in the Marigny, with its strip of live Music venues. And of course, we are renowned for Mardi Gras, which we call “the best free party in the world.” In addition, our food and music festivals, such as French Quarter Fest, Jazz Fest, Satchmo Summer Fest, and others, bring out locals and visitors from around the world to experience America’s most unique city, with an Afro-Caribbean vibe found nowhere else.

New Orleanians are some of the warmest, most hospitable and embracing people in the world, but endemic poverty contributes to the higher rate of crime here compared to other American cities. Our city thrives on tourism, but it is best to take the same precautions as you would in other major cities.

New Orleans is a city of neighborhoods, from the leafy live oak lined streets of Uptown to the closely packed shotgun houses and arts and crafts cottages of the Bywater, all radiating out from the hub of the French Quarter, the original imprint of the city. Most first=time visitors tend to stay in or near the French Quarter. With its high concentration of hotels, tourist attractions, restaurants, nightlife, and walkability, it provides a good entry point into the city. For those looking for a quieter, less touristy area, the Uptown corridor between St. Charles and Magazine Street is ideal, with a variety of restaurants and shops, and easy access to the historic green streetcar line that runs between Carrollton Avenue and Canal Street. For those who want a more unique neighborhood feel, Mid-City, with its classic Creole Italian spots and neighborhood bars is a good option. And the Marigny and Bywater, with their distinct Caribbean vibe, walkability, and access to the Mississippi River at Crescent Park, are both excellent choices.

The New Orleans climate is subtropical, and the most pleasant time of year to visit is from October to May. This time of year is ideal not only because of the weather, but because of the range of activities available. New Orleans is crazy about American football, and the hometown New Orleans Saints are followed with a religious frenzy. Catching a Saints game at the Super Dome is about as New Orleans as it gets. New Orleans also puts on for the holiday season, and from Thanksgiving through the New Year the city comes alive with lights and festivities. This is the time of year to dine at one of the Reveillon dinners that happen throughout the city. This multi-course dinner was originally held after Catholic midnight mass on Christmas Eve, but now occurs throughout the Christmas season. On January 6, the twelve days of Christmas end and Mardi Gras begins. While Mardi Gras Day, or Fat Tuesday, is the culmination of the revelry, the Carnival season runs from Twelfth Night until early February or sometimes early March, depending on the Catholic calendar. And as winter gives way to spring, festivals season begins, with world classic music and food and fun.

For visitors, New Orleans is still less expensive than other destination cities. While our economy is tourist based, once you venture outside the French Quarter and into the neighborhoods of the city, local restaurants, bars and clubs can still be found that offer $10 po’boys and $3 dollar beers. National chains are the exception here, not the rule, so expect good value from local establishments.

New Orleanians love to argue about food. Behind the Saints, it is our number one sport. While New Orleans has many iconic foods, gumbo is the food we are most closely associated with. Gumbo is the quintessential example of the Creolized foodways of New Orleans. African, Caribbean, Indigenous, French, Spanish and Italian influences can all be seen in various iterations of the dish.

Not quite soup, but not stew either, New Orleans gumbo at its essence is a roux thickened broth spiked with local ingredients. What the ingredients are, the consistency of the gumbo, the darkness of the roux, tomatoes, or no tomatoes, filé or okra, are all points of contention. The dish typically begins with a roux of flour and fat, cooked to a desired degree of doneness, from a peanut butter to a dark chocolate color, although there are variations on this too. From there the, our holy trinity of onions, bell peppers and celery are added, as well as garlic and creole seasoning, which typically consists of salt, black, white and cayenne pepper, garlic powder and onion powder. Herbs are also added at this time. The stock used in gumbo can be seafood, chicken, or a mix of both. Chicken and sausage gumbo, usually made with a dark roux, is the most basic version of the dish. Creole gumbo, with its rich shellfish stock, can contain chicken, ham, gizzards, shrimp, crab, hot sausage (chaurice) and smoked sausage. It may contain filé powder (a thickener made from ground sassafras roots), okra, or sometimes both (although not typically).

In addition to gumbo, not to be missed New Orleans foods are po’ boy sandwiches, which are typically filled with fried seafood, roast beef, hot sausage or ham and cheese; beignets, a fried French-style doughnut; chicory spiked café au lait coffee; Creole fried chicken; and Vietnamese offerings such as pho and banh mi.

Early on in the Covid pandemic, New Orleans was hit especially hard, but has since become a leader in the state in vaccination rates, with at least 81.6% receiving at least one dose of the vaccine. Currently there are no indoor vaccination or masks requirements, but that is subject to change. For more information check out https://Nola.Ready.Gov.

New Orleans’ Louis Armstrong International Airport (MSY) is accessible by direct flights from most national and international airports. The best way to travel to and from the airport is via airport shuttle, taxi, Uber or Lyft. The airport is located approximate 20-30 minutes from the city center. It is recommended to arrive at the airport two hours before a departing flight.

While often thought of as an adults’ playground, New Orleans is a great city for children. The Audubon Institute runs a world-class zoo, aquarium and insectarium with a focus on programming for kids. The Children’s Museum in City Park is filled with exhibits to captivate young minds. Our parks, playgrounds and bike paths provide ample opportunities for play and exercise. For families with very young children, New Orleans can be challenging. Our streets and sidewalks are generally not stroller friendly, and the heat can be overwhelming at times. With proper planning, however, the city is a joy for children.

New Orleans is a subtropical climate, and in the winter, nights can get as cold as 32 F, and in the summer over 100. The winter months usually average in the mid-50s to low 60s, but it is not unusual to see days in the 70s and 80s during this time. February and October are the driest months of the year, while June through August are typically the wettest. Rain is a frequent occurrence in New Orleans, and overall the humidity is generally high here. Our most pressing threat are hurricanes, and hurricane season begins on June 1 and ends November 30, with August and September being the most active months. When visiting New Orleans, rain boots and an umbrella are advised. During the winter, a warm coat is recommended, and during the summer, cool, breathable clothes, a hat and sunscreen.

The closest beach to New Orleans is in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, about an hour drive away.

New Orleans is home to some of the best restaurants in the United States, and is known for our unique Creole culinary viewpoint. Fine dining establishments such as Coquette, Commander’s Palace, Galatoire’s and Restaurant Revolution sit at the high end of the spectrum, joining neighborhood favorites like Dooky Chase’s Restaurant, Clancy’s, Patois, The Franklin, and Gabrielle. But above New Orleans is a city of joints, and most memorable meals are often found in the most unassuming places. Liuzza’s by the Track, tucked away by the Fairgrounds, serves a memorable Creole gumbo and a divine BBQ shrimp po-boy. Dong Phuong Restaurant, in New Orleans East, serves a full repertoire of traditional Vietnamese dishes. Mandina’s, in Mid-City, is the classic Creole Italian joint. And Zimmer’s deep in Gentilly, serves fried seafood po’ boys that are worth the drive.

For breakfast or brunch, decadent favorites like Brennan’s, Surrey’s and Elizabeth’s as well as newcomers like Toast, are solid, and our go-to is Buffa’s. You can grab a quick bite at Bywater Bakery and soul food at Two Sistas ‘N Da East, or drive up for a crawfish boil at NOLA Crawfish King.