Cafe Allende’s manager, Roberto Hernandez, stands behind the counter, serving customers pan chino out of a display case grown foggy from the warmth of the fresh pastries inside.

“The idea was to come and study, finish school, and work as a technical engineer. But it didn’t work out that way. This pulled me in,” he says, gesturing around the cafe. “Now it’s my life.”

Roberto had come to Mexico City as a boy, moving in with a sister 20 years his senior and her husband, Jesús Chew, a Chinese immigrant and the owner of Cafe Allende. Welcomed into their family as another son, Roberto worked at the cafe and spent many evenings with Jesús, learning Mexican-Chinese recipes like the varieties of pan chino, which means “Chinese bread” in Spanish.

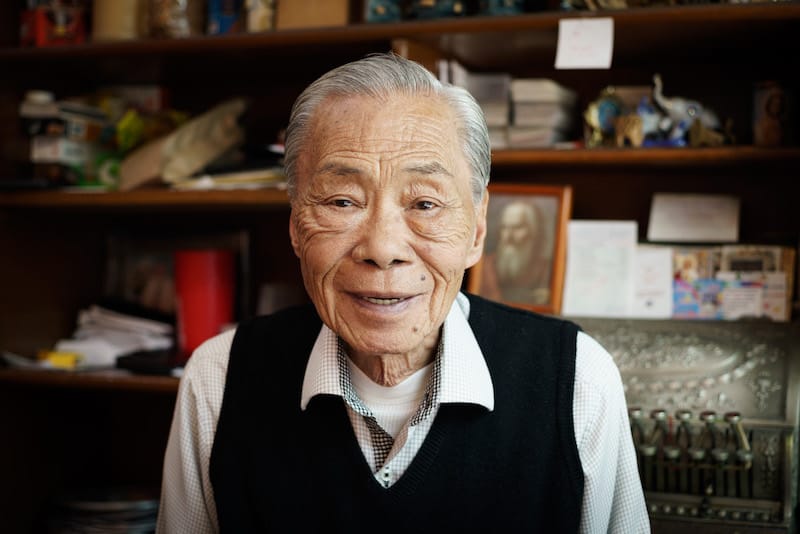

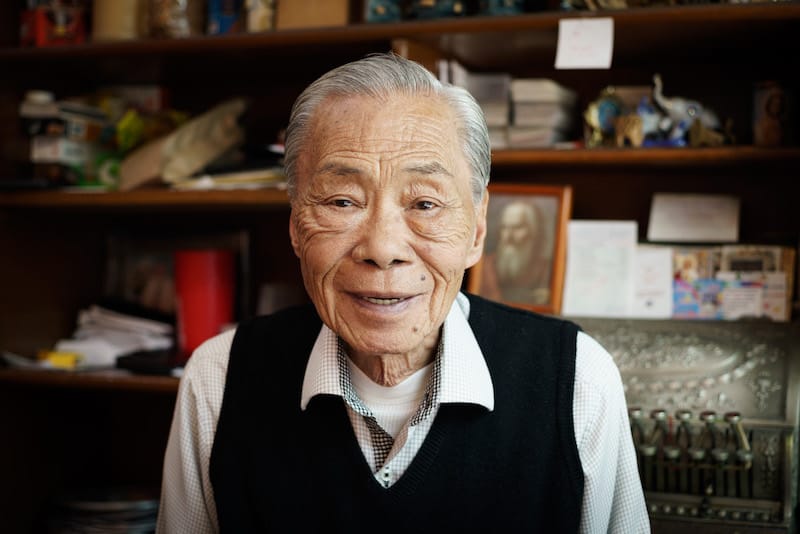

Denser versions of the typical sweet Mexican breads you would find at most bakeries, pan chino is a reminder of the history of Mexico’s Chinese community, and of the history of joints like Cafe Allende itself. The now 80-year-old Jesús takes us back to the 1950s, when he first arrived in Mexico City from China. Something in his story echoes Roberto’s plans gone sideways.

“At the beginning, I didn’t like it [here],” Jesús tells us. He was 15 years old, and had come to help his father, who had arrived a few years earlier hoping to earn his fortune across the ocean, eventually purchasing Cafe Allende from a fellow Chinese immigrant in the 50s. There was no love lost between father and son, Jesús says, describing his father as a harsh man, difficult, with a temper, but very educated.

“I didn’t have the opportunity to study, but at the house there were a lot of Chinese books – very old – literature, philosophy,” he says, looking back. “So, I would come home and take down a book and look for the words that I didn’t know and, even if he was in a bad mood, he would explain them to me.”

That’s how Jesús learned to read Mandarin and Cantonese while also studying Spanish. It took him three years to master Spanish well enough to interact with customers. When he felt his son could manage the business on his own, Jesús’s father eventually returned to China. “I wanted to go back to study, but it wasn’t possible. I couldn’t go back. I had to stay to feed my mother, my brothers and my father.” Jesús continued sending money to his family across the Pacific, while running the small Cafe Allende, which sits on a bustling street behind Garibaldi Square in downtown Mexico City.

Recently arrived immigrants made Mexican cuisine their own, adapting local recipes with touches of Chinese influence.

This story is not unlike that of many other Chinese immigrants to Mexico City in the first half of the 20th century, arriving after earlier waves of migration in the late-1800s. Most came as laborers, without money, connections or the ability to speak Spanish. Many found work in places like Cafe Allende, part of a trend of cafes Chinos (Chinese Cafes) that were small, cheap diners run by recent Chinese arrivals.

The cafes served as havens for the working-class poor of Mexico City, serving not only immigrants, but Mexican laborers and students as well, anyone needing a cheap meal in a friendly setting. While the menus included Chinese dishes, the cafes weren’t Chinese restaurants per se. Their most popular items were Mexican favorites like huevos a la Mexicana or chilaquiles.

“It was something you could do without having to talk,” another cafe Chino owner tells us, when explaining why much of Mexico’s Chinese immigrant community took to cooking and baking. In doing so, recently arrived immigrants made Mexican cuisine their own, adapting local recipes with touches of Chinese influence. Their pan Chino became the most famous offering, and it’s still debated among scholars and cafe owners themselves what exactly makes it special. Some say it’s the clarified pork fat, some say it’s top-shelf ingredients, some say it’s the excellent Chinese bakers.

“I had a Chinese baker, and a Chinese cook, but they were already very old,” Jesús says about the early days at the cafe. “The baker was 78 years old [and worked without] mixers – he worked with his hands. The cook was 76 and he could barely walk, but worked so that he wouldn’t starve. So I would run the cash register and at the same time help make the bread and cook. A thousand jobs. But we started to make a little more money, and I was able to send a little more money to my mother and father.”

Thanks to Jesús, both his younger brothers were able to get an education, first in China and then in the United States. One went on to become a scientist with NASA, the other, to work for MIT. Jesús may have barely had enough to survive, but he always sent money home.

“I was alone here. Without a family, without anything. I made a few pesos and I sent them to my mother to feed my two brothers, who were still really small at the time. But I was making so little money that it cost three pesos to go get a haircut and … I didn’t have it. It was a difficult time.”

Fifteen years into running the cafe, Jesús met his wife, Obdulia. She was working as a waitress at her family’s restaurant in the St. Maria de Ribera neighborhood. “I went into a cafeteria to drink a coffee and saw a really beautiful girl at the cash register, and … I started to go see her every day,” Jesús says.

After several months, he worked up the nerve to ask her out and, two years later, they were married and began to run the cafe together. Jesús raised his own three children along with his brother-in-law Roberto, sending them to college with money made at Cafe Allende.

Over the years, the cafe has become a neighborhood staple and Jesús knows everyone that walks through the doors. Customers come by to greet him on Saturdays, the only day that he comes to the cafe now due to Covid. The pan chino here continues to be renowned, and even folks that have moved out of the old neighborhood come back for a concha or a biscuit to-go.

With a menu that no longer includes Chinese dishes, new customers might have no idea of the diner’s history – one of the last remnants of the 20th century wave of Chinese immigrants to Mexico. But sit for a spell and it’s easy to feel the sense of community and family that still permeates this cafe.

Published on March 23, 2022

Related stories

February 13, 2024

New Orleans | By Pableaux Johnson

New OrleansIn the spring of 2017, the Bywater Bakery opened its doors and became something of an “instant institution.” Part casual restaurant and part impromptu community center, the cafe space hummed with perpetual activity. Deadline-racked freelancers posted up with their laptops, soon to be covered in butter-rich pastry flakes. Neighborhood regulars would crowd tables for a…

January 3, 2024

Mexico City“You can’t call yourself Mexican if you don’t eat rosca de reyes,” jokes Rafa Rivera, head baker and owner of Forte Bread and Coffee in Mexico City. Distracted, he stops grating orange peel long enough to muse about the king’s cake he is making. Only 29, he already has several businesses under his belt, and…

August 12, 2022

Mexico CityOn a neighborhood back street, hemmed in by cars on both sides, sits a house-turned-secret dance club, a girl selling Maruchan soup-in-a-cup under a pop-up tent, and La Chubechada – a tiny storefront with a cutout window just big enough for Maria Guadalupe to poke her head out and take your order. When your drink…