They say rules are made to be broken. As for traditions? Well, they change with the times.

In Japan, people opting for new year noodles will most likely pick soba buckwheat noodles. Often eaten on New Year’s Eve as “toshikoshi soba” (literally, “year-crossing noodles”), which are served in a light dashi broth, they symbolize good luck, longevity, and breaking off the hardship of the previous year.

During the chilly days of January, however, we find ourselves craving a different kind of noodle to start the year: tantanmen. Punchy, oily, and spicy wheat noodles topped with minced pork, this gloriously fiery dish might not give us a long life, but it’s something we’re planning to eat life-long.

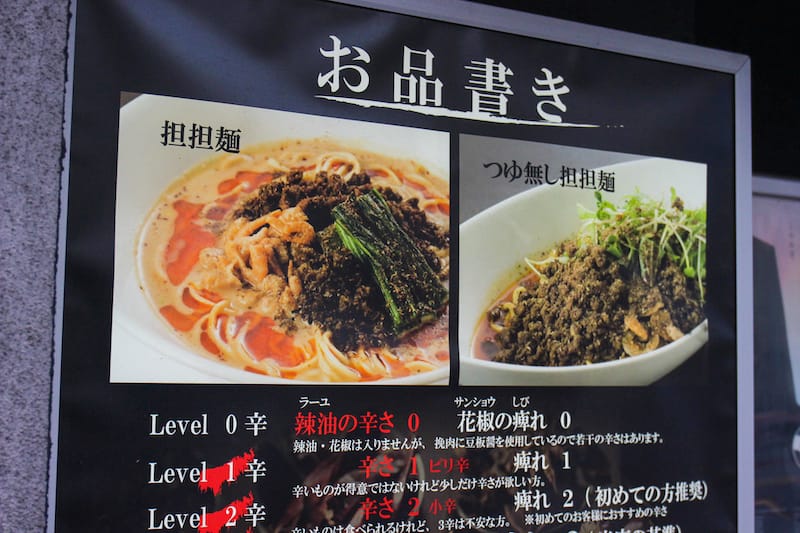

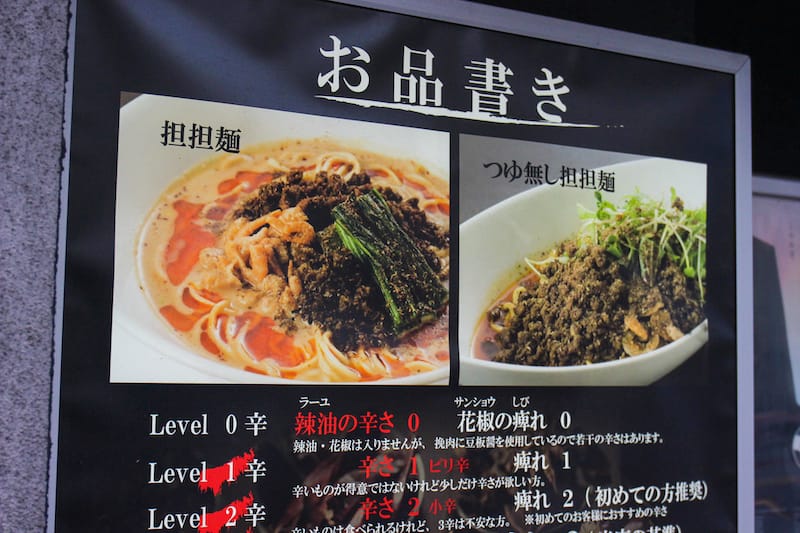

There are primarily two types of tantanmen: shirunashi (dry noodles – literally, “without soup”) in which noodles are mixed with chili oil and other spices, and shiruari (“with soup”) in which noodles are served like ramen, swimming in a bowl of hot broth that is often thick and creamy with sesame paste.

The history of the dish, however, is as cloudy as that soup. Known as dandanmian or dandan noodles (literally, “pole-carried noodles”) in China, it began as a street snack born in the 1800s in Sichuan province. Traders who would carry bamboo poles balanced across their shoulders with a bucket on each end, one for noodles and one for sauce, peddled the snack to hungry passersby.

In traditional recipes, minced pork is stir-fried in chili oil with preserved vegetables, sweet bean sauce, shaoxing wine and, of course, numbing Sichuan pepper, along with many other spices. The noodles are thin and white, made with wheat flour and egg whites.

What’s striking is that there’s no sesame and no soup, despite that being the most common version found across Japan today.

The sesame broth version is believed to have been created in Hong Kong by Yeung Din-Wu, a former chef of China’s imperial court. He opened a Sichuan restaurant called Wing Lai Yuen in 1947 where he introduced dandan noodles with a creamy sesame paste and peanut butter broth to please the palate of local diners. He also served a different kind of noodle made from a combination of soft and hard flour.

Japanese accounts tell a different story. They attribute the recipe to Kenmin Chen, known as the father of Sichuan cuisine in the country. However, he didn’t arrive in Japan until 1952, having passed through several regions in mainland China, Taipei and – importantly for our tale – Hong Kong in 1948. It was there that he opened a Sichuan restaurant, and where he could easily have come across Yeung’s recipe, especially since they effectively would have been competitors.

Whatever its origin, tantanmen is now found widely across Japan. A search on a restaurant review database turns up more than 1,800 stores that offer it, ranging from tantanmen specialty shops to Chinese restaurants. Many are ramen shops that have added it to their menus as simply another kind of ramen.

For our new year tantanmen pilgrimage, however, there’s only one place that will do. We head to Yushima, an area just to the southwest of Tokyo’s beautiful Ueno Park. Here lies our destination: Sichuan Tantanmen Aun. It’s a relatively small and nondescript restaurant, but its entrance is often marked by a queue of patient diners; we are far from the only devotees in its thrall.

The inside is bright and welcoming; even families with young children will head here for a tantanmen fix. The menu offers both shirunashi and shiruari versions, with both white and black sesame options. Among Aun’s kodawari (specialties), it boasts of homemade chili oil made from nine kinds of medicinal herbs and spices; Sichuan peppercorn (with only the outer part used for the strongest flavor); tianmian, or sweet bean sauce, made from three-year aged umami-full Hatcho miso; and doubanjiang or tobanjan, spicy bean sauce, made from a blend of two regional varieties.

Once we’ve selected our tantanmen, we must choose the level of spiciness from the chili oil and the level of numbing from the Sichuan pepper. The scale runs from 0 (none at all, an option great for kids) to 6 – customers who choose the highest level pay a 100-yen surplus for the privilege or the pain. As always, we order level 5 for both; is this a symbol of our devotion or our addiction? Is this the year we should take things to level 6?

Our bowl of white sesame shirunashi tantanmen arrives in a wide oval dish that’s full of promise. The thick noodles are yellow, made with alkali, giving them their pleasing elasticity. They’re nestled in fiery-red chili oil and sesame paste, and topped with aromatic minced pork, peppered, dried shrimps, and mizuna that adds a vibrant green contrast. The floral scent of the Sichuan pepper is warm and intoxicating.

Once well mixed, the journey begins. Each noodle is coated in equal amounts of fire and ice: the heat of the chili and tingly numbing of the Sichuan pepper. Sometimes the numbing can be so intense that it’s hard to coordinate throat muscles needed for swallowing. It’s a near-spiritual experience for the taste buds; there is no option but to finish the bowl.

Occasionally, we dabble in the pleasingly rich and creamy shiruari version, or add a side of char siu-topped rice, almost as a palate cleanser. Time and time again, however, we return for the rush of shirunashi, the strength and complexity of the spices and scents.

This tantanmen, coated in sesame and served in belly-filling bowls, is a far cry from the small and humble Sichuan street snack. But dishes evolve, just like traditions.

Published on January 19, 2023

Related stories

February 8, 2024

TokyoThere’s a pocket of Tokyo, strolling distance from the stock exchange and the former commercial center, which feels like a step back in time. Ningyocho is filled with stores specializing in traditional crafts, some more than 100 years old. Here you can buy rice crackers or traditional Japanese sweets or head for a kimono, before…

November 28, 2023

TokyoThe Gion district of Kyoto embodies the romanticism that surrounds Japan’s ancient capital. Filled with machiya (traditional long wooden houses), it harbors several “teahouses,” where geiko — the Kyoto term for geisha – entertain their high-class guests with quick-witted conversation and skilled musical performances. Yet just north of Shijo Street, the neighborhood evolves into a…

September 7, 2023

Tokyo | By Culinary Backstreets

TokyoEditor’s note: In the latest installment of our recurring First Stop feature, we asked chef and ramen expert Ivan Orkin about the first dishes he craves when he returns to Tokyo. Ivan is originally from the U.S. but has spent much of his life in the Japanese capital. He is the author of The Gaijin…