Winding between the teenage fashion havens of Harajuku and Shinjuku is the ultra-hip Cat Street, lined with countless second-hand clothing stores and embellished with a single origin coffee shop. Just a stone’s throw to its south lies a nondescript concrete building.

Unassuming from the outside, for the past 15 months its second floor hid a sake bar. The interior was a stylish and modern take on Japanese design – a sleek counter in the center, tatami mats and sliding doors splitting the space into three. Here, a young crowd gathered, sampling the latest sake and regional dishes – from Miyagi beef tongue meatballs and Iwate squid sashimi to Akita smoked pickled daikon topped with cream cheese.

Given its relatively short residency, one might be forgiven for thinking the bar was a trend or a poorly conceived dream. But Mysh (pronounced “my shu” meaning “my sake”) didn’t go out of business, nor were any of its members of staff full time. Their lease having expired, the founders decided to take some time out before finding a new home – time to review their goal of creating something more than a dining establishment, of creating a community space. Currently, the bar only exists as a monthly pop-up event, but its founding story and model are indicative of Tokyo’s broader culinary culture – one that is simultaneously steeped in tradition while constantly reinventing itself under the city’s bright neon lights.

A metropolis of nearly 14 million people, Tokyo is unashamedly trendy and rapidly matches the taste of its modern urbanites. Acutely attuned to the dining scene in New York, it’s only ever a few paces behind importing the latest fashionable gastronomy. Indeed, the country has a long history of doing so. When Japan finally opened its borders to the outside world in 1868, marking the start of the Meiji era, it was quick to develop and embrace yoshoku – its own versions of Western classics – such as hamburg, hamburger patties topped with Japanese-style demi-glace sauce or the more bizarre Napolitan which adds Japanese green peppers and frankfurters into a ketchup spaghetti mix. While much of this kind of cooking is now distinctly uncool – the preserve of smoky cafeterias one’s grandfather might visit, newspaper tucked under one arm – culinary creativeness continues unabated. A recent (re)invention is soufflé pancakes, popular for their fuwafuwa (soft and fluffy) texture that torokeru (melts) in the mouth, and cafes are often easily identifiable from a young crowd waiting patiently outside for a seat.

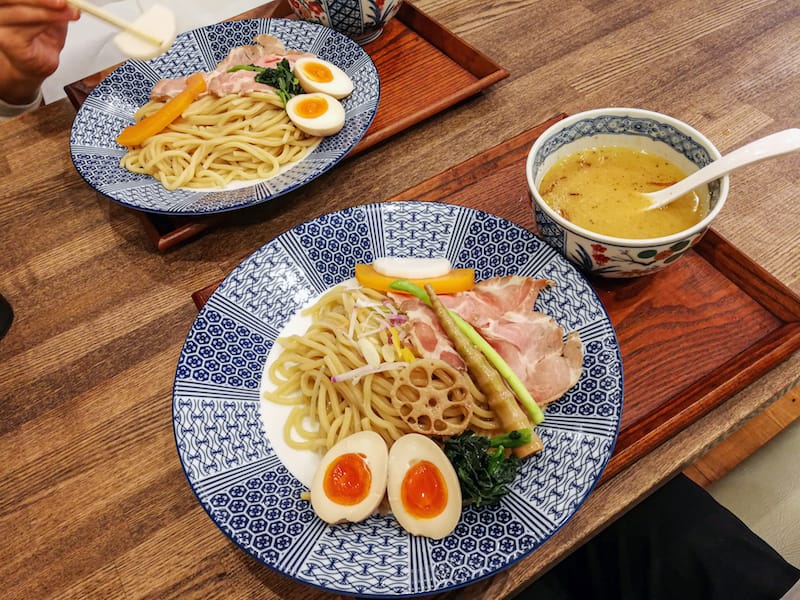

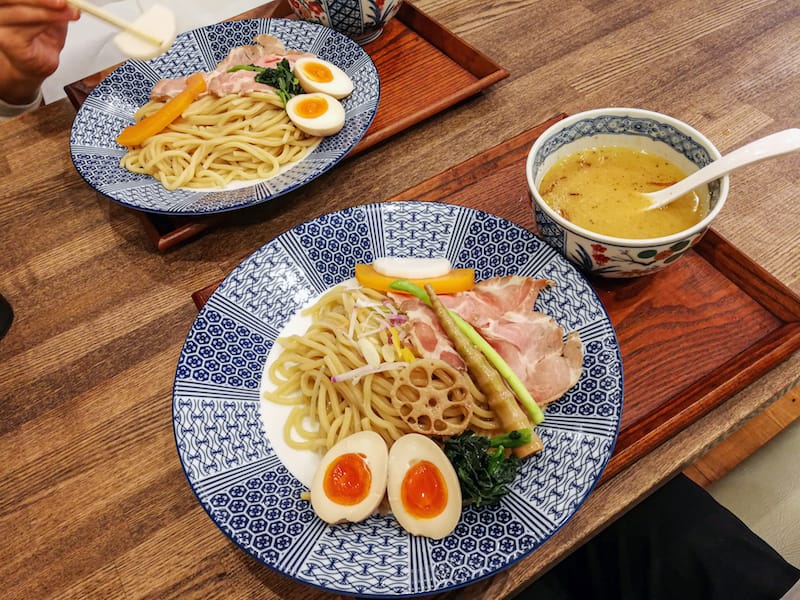

The custom of queueing for the latest food fad is deeply ingrained in a Tokyoite’s psyche, with many claiming that the deliciousness of the desired dish increases with the wait time. Two hours or more is not unusual. Media holds massive sway. TV shows cover food with fetishistic fervor, agonizing close-ups and slow-motion spoon action, and bestow whatever they film with multiple cries of “oishi!” or “umai!” (delicious). The result is overnight queues of excited customers, gawping at pictures online before they can take their own. Leveraging the power of social media, stores now compete to produce the most insta-bae (Instagrammable) dishes.

Less transient has been the transformation of the Tokyo coffee scene. Japan is renowned for its kissaten culture, dark and smoky establishments preserving the Showa-era aesthetic, with drip coffee presented in porcelain cups. From the economic bubble of the mid-late 1980s, chain stores gathered steam with Starbucks becoming the library or office of choice, housing students or mobile workers for six-hour stints or more. Yet in the past few years, independent stores specializing in third-wave coffee have sprung up, bringing freshly roasted beans to freshly inaugurated hipsters nationwide. Light and airy with minimalist furnishings, these shrines to caffeine are even sought out by international visitors who no longer complain that they can’t find a decent cup, and instead patiently join the lines.

When evening rolls in, Tokyoites are definitely not opposed to a stronger brew. Sake is experiencing a massive boom, although some would say this is too little too late. Despite being considered Japan’s national drink, domestic consumption of sake peaked in 1973, as cheaper alternatives and exotic imports saw it fall out of favor. A lack of sales and successors is pushing breweries to close their doors every month. Yet there is a trickle of young people heading into the industry, bringing an understanding of modern customers’ tastes and an open-mindedness that makes them more prepared to experiment with new techniques and technology. Sparkling sake and different fruit flavors are flooding the market; labels are becoming creative and cute; and there are even apps that use AI to help customers determine their palate. Sleek and stylish bars are on the rise, providing an environment attractive to young people and women, and helping to shed sake’s image as a drink for old men.

This youthful energy helped give rise to the migratory sake bar Mysh. Taking advantage of the rise in pop-up events, Hiroto Mukai, business consultant with a passion for starting ventures, and Sachie Ogawa, crowned Miss Sake 2015 in a beauty-pageant-meets-sake-promotion, ran a monthly sake bar event over the course of a year while gathering supporters and staff – an important strategy given their goal of creating a casual community space in a metropolis of millions.

With local dishes from all over Japan on the menu, Mysh also reflects the huge effort being poured into regional promotion to help Japan’s fading rural communities. Facing an aging population, an extremely low birth rate and high rural-to-urban migration, the countryside is becoming one of shutter towns, despite the government offering subsidies and other benefits in a desperate bid to make rural life more attractive. For many young people, however, it’s not always the glittering lights of the city that draws them in, but the lack of jobs locally that pushes them out. Many of Mysh’s staff bring back produce from their hometowns to show off the soul food that raised them at specially-themed nights.

These efforts – along with a growing farm-to-table movement – have been helpful in sowing seeds to support rice farmers. Several restaurants and new oshare (stylish) onigiri stores proudly advertise their sources with detailed profiles on the producers. Rice consumption has more than halved since its peak in 1962 – a sharp decline, especially given it is considered integral to Japanese cuisine and good nutrition. Taught in schools is the concept of ichiju-sansai, which roughly translates as “one soup, three dishes”: the ideal diet should contain a main dish consisting of protein, with two vegetable-based sides, alongside a soup and accompanied by a shushoku, a staple food rich in carbohydrates. Yet nowadays a common conversation starter might ask about breakfast habits: are you a rice person or a bread person?

Japan has been doing a lot of reflecting on bigger questions in recent months. The country has just witnessed the abdication of Emperor Akihito, resetting the Japanese calendar and marking the start of the era of Reiwa, or “auspicious peace.” This historic moment has provoked much nostalgia over the previous Heisei era, accompanied by a sense of unease as people contend with an economy that has been stagnating for nearly 30 years. Companies are no longer able to guarantee lifetime employment, and a chronic labor shortage means the labor market is near its tightest level in 45 years. Businesses are recognizing the dire need for innovation, but it seems change is slowly creeping in. Start-up accelerators and coworking spaces on the rise in an attempt to break out of the traditional and restrictive mold of doing business.

Simultaneously, like those at Mysh, a small but growing number of young people are taking a different approach to work. “Everyone here has side jobs,” says Mukai, who runs his own consultancy and has recently said goodbye to a food truck, from which he sold takoyaki (octopus dough balls). This strikes a contrast with a country where the work structure has traditionally revolved around dedication to one company, and the notion of “side gigs” is not widely understood nor accepted.

Tokyo is now gearing up for the 2020 Olympics, which is providing another opportunity for city businesses to reconsider how they do things. As the start date of the Olympics approaches, dining establishments are beginning to realize that failing to adapt to overseas visitors’ tastes is a missed opportunity – and a badly translated English menu doesn’t cut the mustard. The vast majority of restaurants still offer no vegetarian or vegan options, although awareness is slowly growing. Renowned ramen chain Ichiran has just opened a pork-free branch in Shinjuku, and vegan ekiben – lunchboxes for a train ride – have been popping up at some stations.

Preparations for the Games are also pushing through vast redevelopment. Tsukiji – which was known as the world’s largest fish market and “Tokyo’s kitchen” – closed in October 2018 and was transported to a purpose-built yet clinical facility in Toyosu. Tourists are now kept well away from business and the market has more space. But intermediate wholesalers are complaining their sales have fallen since the move, and the long-term decline in trading volumes looks set to continue. Consumers were already eating less fish, but with the move, the social fabric of the market has been torn; the threads of invisible relationships between people, place and space ruptured.

Drastic though some of these shifts may seem, Tokyo’s appetite has long been in flux; new structures will evolve with time. As in any metropolis, production and consumption give rise to ever-shifting patterns and ever-shifting tastes. It takes just a glance at the state of the stomach to also glimpse the underbelly of a city’s challenges and changes.

Editor’s note: Traditionally we have published State of the Stomach pieces when beginning coverage of a new city, to provide an introduction to its food culture and how it shapes daily life. But as we dive deeper into the cities we work in, we’re taking stock of what’s changed, particularly as internal and external factors reshape both the culinary and urban landscape. So we thought it was worthwhile to reexamine how some of these cities are eating, which will inform our coverage going forward.

February 5, 2016 Auspicious Eating

February 5, 2016 Auspicious Eating

As the moon starts to wane each January, people throughout China frantically snatch up […] Posted in Shanghai January 8, 2018 Going Deep

January 8, 2018 Going Deep

As the calendar year turns over, we’ve grown accustomed to the barrage of lists telling […] Posted in Rio, Special category July 20, 2018 Kyr-Aristos

July 20, 2018 Kyr-Aristos

The late Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis may be world-famous, but no one could […] Posted in Athens

Published on June 06, 2019

Related stories

February 5, 2016

ShanghaiAs the moon starts to wane each January, people throughout China frantically snatch up train and bus tickets, eager to start the return journey to their hometown to celebrate the Lunar New Year (春节, chūnjié) with their family. This year, revelers will make an estimated 2.5 billion journeys on the train system alone, up 100 million from…

January 8, 2018

Rio | By Culinary Backstreets

RioAs the calendar year turns over, we’ve grown accustomed to the barrage of lists telling us where to travel during the next 12 months. Oftentimes these places are a country or even a whole region – you could spend an entire year exploring just one of the locations listed and still barely make a dent.…

July 20, 2018

AthensThe late Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis may be world-famous, but no one could have guessed that he would be the source of inspiration for a neighborhood kebab place in a residential suburb of Athens. Onassis, who was commonly called Ari or Aristos, was born in 1906 in Smyrna (now Izmir, Turkey), only to later…