In the early 1980s, Xue Shengnian was a farmer out in the village of Hongqiao. On the side, he painted houses and factories to try to make ends meet. Then he heard that the economic liberalization known as Reform and Opening was allowing citizens to start private restaurants and he thought to himself, “I know how to grow the vegetables; I bet I can cook them too.” So he opened A Shan in 1983, only the second restaurant ever in an area better known for its fields than its food.

Newly emerging from the days of collectivized agriculture, the government still rationed food, which required this budding cook to get creative with his supply network. To find beer for his clientele, Xue drove over provincial lines to a brewery, where he made friends with the boss, currying guanxi to buy the drink right from the taps. To stock rice, he turned to the gray market, buying up surplus ration coupons from friends, then friends of friends, to keep up with demand at the restaurant. He woke every morning before the sun to bike into Shanghai proper and shop at the Fuzhou Lu markets, then often stayed up past midnight at the restaurant chatting with customers. The long days paid off, as nothing could have prepared him for the popularity and accolades he would receive.

Newly emerging from the days of collectivized agriculture, the government still rationed food, which required this budding cook to get creative with his supply network. To find beer for his clientele, Xue drove over provincial lines to a brewery, where he made friends with the boss, currying guanxi to buy the drink right from the taps. To stock rice, he turned to the gray market, buying up surplus ration coupons from friends, then friends of friends, to keep up with demand at the restaurant. He woke every morning before the sun to bike into Shanghai proper and shop at the Fuzhou Lu markets, then often stayed up past midnight at the restaurant chatting with customers. The long days paid off, as nothing could have prepared him for the popularity and accolades he would receive.

A Shan only moved locations once, just around the corner in the 1980s, but residents from that era wouldn’t recognize their hometown today. Once a village in its own right, Hongqiao has been swallowed up by Shanghai’s sprawling commerce and industrialization. A sub-district of Changning, it is home to the city’s secondary airport and the sprawling gated communities of expats and wealthy locals. But A Shan stays on the corner of two busy streets, like a time capsule of the days before Shanghai re-launched itself on the world stage as a cosmopolitan city.

Xue has not changed so much as a paint job since the restaurant opened more than 30 years ago. The derelict sign outside is faded – once a bright red, it’s now barely pink – and the glass windows are practically opaque thanks to years of tobacco buildup. Despite the 2010 ban on smoking in restaurants, diners here light up at almost every table, including Xue himself, who chain-smokes while giving recommendations to new diners. This throwback to the days gone by is the reason A Shan has so many loyal customers. They also count on the fact that the menu remains unchanged.

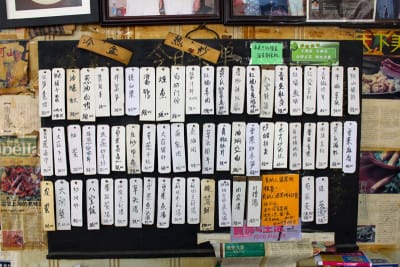

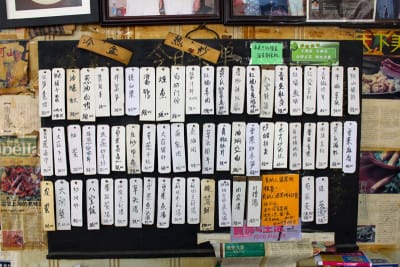

Xue found inspiration by recreating his grandmother’s and mother’s home-style cooking, all based on taste memory. At the restaurant, dish names are painted vertically on wooden slats hung on the wall and are removed when sold out or out of season. We no longer have to order when we arrive – we just tell Xue how many dishes we want, and he is happy to take care of the decision-making for us. His classic shrimp fried with cucumbers (黄瓜漏虾, huángguā lòu xiā) usually finds its way to our table, a seemingly odd combination that works well, pairing plump shell-on crustaceans flash-fried with softened cucumber in a crisp, clean sauce. The red-braised cooking technique so famous in Shanghai cuisine almost always makes an appearance, usually in the form of braised meaty fish tails (红烧划水, hóngshāo huà shuǐ), although pork belly is not out of the question.

Xue found inspiration by recreating his grandmother’s and mother’s home-style cooking, all based on taste memory. At the restaurant, dish names are painted vertically on wooden slats hung on the wall and are removed when sold out or out of season. We no longer have to order when we arrive – we just tell Xue how many dishes we want, and he is happy to take care of the decision-making for us. His classic shrimp fried with cucumbers (黄瓜漏虾, huángguā lòu xiā) usually finds its way to our table, a seemingly odd combination that works well, pairing plump shell-on crustaceans flash-fried with softened cucumber in a crisp, clean sauce. The red-braised cooking technique so famous in Shanghai cuisine almost always makes an appearance, usually in the form of braised meaty fish tails (红烧划水, hóngshāo huà shuǐ), although pork belly is not out of the question.

Sweet, shredded eel (鳝丝, shàn sī), fried in the oil that also sauces the dish, is topped with Chinese mirepoix: green onions, garlic and ginger. Preserved plums, reminiscent of a sweet Oriental chutney, are famous here. On a recent trip we also sampled preserved mustard greens fried with winter bamboo shoots, shaved into thick, crinkle-cut chips (雪菜冬笋, xuě cài dōngsǔn), a new favorite we plan to request in the future.

Xue is now 68 and known better as A Shan than his actual surname, so he has given up slaving away in the hot kitchen most days and holds court in the dining room instead (where he also naps on a makeshift cot made up beside crates of beer every afternoon at 4 p.m. for about half an hour). His backdrop is a wall of calligraphy and photographs supplied by prominent movie stars, talk show hosts and other famous fans of the restaurant. He only takes 12 days off annually at Chinese New Year, but he does not look forward to his lonely vacation. During the holidays, he eats Shanghainese paofan twice a day (a basic meal of boiled rice with a few garnishes for flavor) and misses his customers. He’s happier preening in front of his loyal regulars as he takes orders, tallies up bills and poses for pictures with his foodie fans, always with a cigarette in hand and a recommendation at the ready.

April 12, 2016 Every Shade of Green

April 12, 2016 Every Shade of Green

In Shanghai, wet markets hold the telltale signs that spring is finally upon us. Stalks […] Posted in Shanghai August 27, 2015 Yuyang Laozhen

August 27, 2015 Yuyang Laozhen

Editor’s note: We regret to report that Yuyang Laozhen has closed.

Shanghai’s farm […] Posted in Shanghai March 11, 2022 Nanjing Soup Dumpling

March 11, 2022 Nanjing Soup Dumpling

Any Shanghai denizen who has lived in the city for longer than a few months worships at […] Posted in Shanghai

Published on March 11, 2015

Related stories

April 12, 2016

ShanghaiIn Shanghai, wet markets hold the telltale signs that spring is finally upon us. Stalks of asparagus as thick as a thumb spring up first, alongside brown and white bamboo shoots so freshly pulled from the earth that dirt still clings to their fibrous shells. But the most exciting spring green is fava beans (蚕豆,…

August 27, 2015

ShanghaiEditor’s note: We regret to report that Yuyang Laozhen has closed. Shanghai’s farm country is closer than most residents imagine, especially when surrounded by the city’s seemingly endless forest of skyscrapers. But just beyond the spires is a huge, green oasis: Chongming. Somewhat smaller than Hawaii’s Kauai, this island at the mouth of the Yangtze…

March 11, 2022

ShanghaiAny Shanghai denizen who has lived in the city for longer than a few months worships at the altar of xiǎolóngbāo (小笼包). These steamed buns of goodness – tiny pork dumplings with a slurp of soup wrapped up in a wonton wrapper – provide delicious fodder for debates among Shanghai’s fiercest foodies. We all have…