The black-and-white photo shows a crowd, a policeman and José Martins holding a piece of salted cod, all crammed together in Manteigaria Silva, a small, historic shop in Baixa. It’s from a newspaper clipping dated December 10, 1977 – Christmas season. That year Portugal experienced a shortage of bacalhau, the beloved salt cod that was (and still is) a Christmas Eve favorite, and the people of Lisbon were so desperate to get their preserved fish that the police were often called in to maintain order. The scene at Manteigaria Silva played out at shops across the city.

José, who still oversees the bacalhau section at Manteigaria Silva, remembers those days well. “Hard to imagine now but people were fighting for salt cod, that’s why we had to call the police,” he recalls. Another photo shows the crowd waiting outside for the chance to get a piece of the precious fish. It stands in stark contrast to the quiet days brought on by the pandemic: This year, unlike any since José has been at Manteigaria Silva, there are no lines for bacalhau.

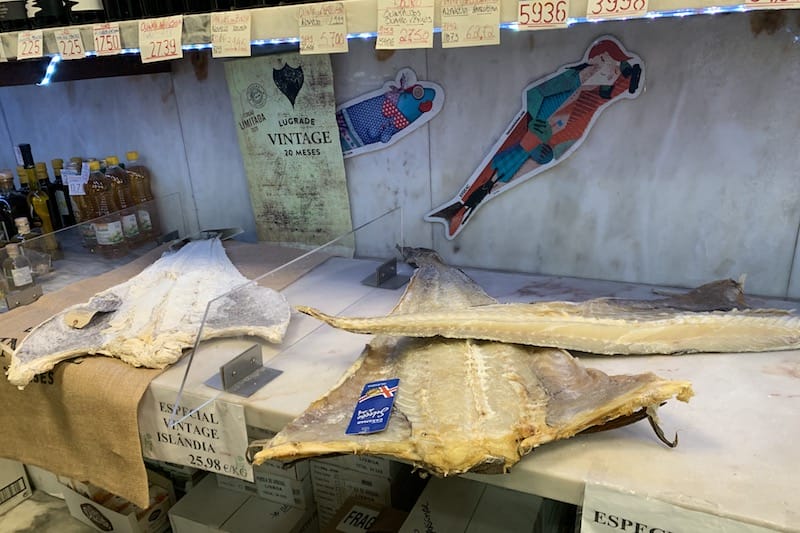

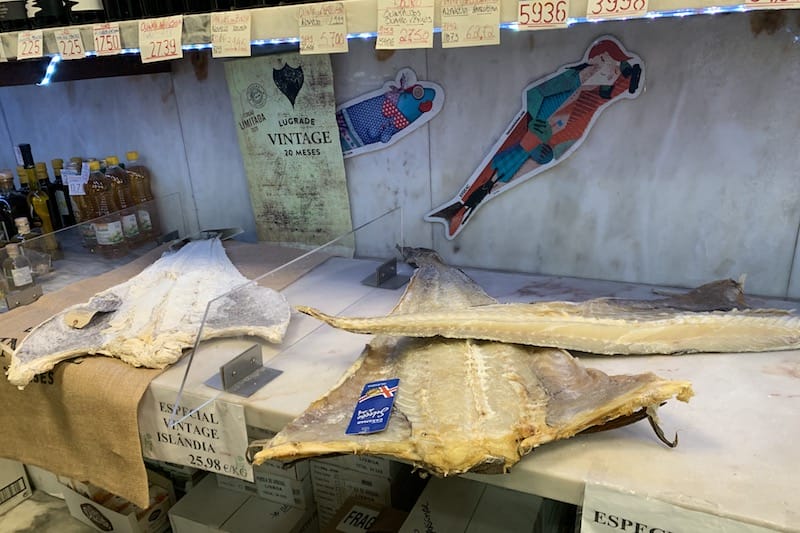

Almost 78 years old, José has been working at this grocery shop for 48 years – over half his life. He likes to tell the same joke – “I’m preserved in the salt!” – while pointing at the photo from 1977. Next to him are various piles of salted cod from Iceland, which differ in terms of size, price and curing process. The exquisite 32-month vintage (priced at €29.50 per kilo) catches our eye. The wide variety makes sense when you consider that bacalhau is an iconic and essential Portuguese ingredient.

Portugal is the biggest consumer of cod in the world, with 20 percent of all cod caught worldwide being eaten in the country. This love for an imported fish, especially when excellent fresh fish can be sourced along the extensive Portuguese coastline, has deep roots in history. Some authors claim that the Vikings, in search of salt, came to what is modern-day Portugal and showed the people living here how to preserve fish, which the Norsemen traded for salt from the saltpans. Later down the line, the Portuguese, like the Basques, went out to fish cod in the Atlantic waters off Newfoundland and the Canadian coast – as early as the 15th century, according to some reports. Cod was easy to preserve for the trip home, as it’s so high in protein and low in fat.

The Portuguese needed fish for religious reasons – meat consumption was forbidden during Lent and on the many fasting days in the Catholic calendar. The Church’s rules on fasting are what led to the tradition of eating bacalhau on Christmas Eve (although octopus has replaced salt cod in some parts of the country). It’s a humble meal: the fish is boiled with cabbage and potatoes, and sometimes eggs and chickpeas (some families now bake it in the oven). But it’s free of meat, as required before Missa do Galo (Midnight Mass).

The preserved cod also proved convenient for long maritime trips. During the 16th and 17th centuries, sailors on the intercontinental crossings to Asia and Brazil ate bacalhau. Over the centuries, salt cod became one of the most affordable animal proteins and was a popular food staple in a poor country, where it was known as the “meat of the poor,” or more recently “the faithful friend” (fiel amigo), one that people could always rely on.

In the beginning of the 20th century, its popularity remained as strong as ever, although supply had begun to shrink. While working as academic researcher, António Oliveira Salazar, an economist by training and the future leader of the Portuguese dictatorial regime, learned that a cod shortage could have a tremendous impact on society. So when he was named Prime Minister in 1932, he prioritized a continual and affordable salt cod supply, as António José Marques da Silva documents in his paper titled “The fable of the cod and the promised sea.” Cod fishing was subsequently a protected industry during the dictatorship; the fleet was expanded and prices lowered. Bacalhau consumption increased all over the country – some claim it tripled – and in the colonies. The so-called “cod campaign,” which ran from 1934 until 1967, continued even during the Second World War: the fishing ships were painted white and allowed to pass over the northern Atlantic.

[Bacalhau] was known as the “meat of the poor,” or more recently “the faithful friend” (fiel amigo), one that people could always rely on.

The fish was offloaded in northern Portuguese ports, namely Viana do Castelo and later Aveiro and Ilhavo. It explains why there are so many different bacalhau recipes in the Minho area of northern Portugal. As a cheap food for the masses, some of the best bacalhau recipes came out of recycling leftovers or the less prized parts of the fish, such as bacalhau à Brás (shredded cod with scrambled eggs and straw fries), pataniscas de bacalhau (cod fritters), pastéis de bacalhau (cod cakes), bacalhau à Gomes de Sá (with potatoes and eggs) and arroz de bacalhau (salt cod in a rice stew).

When protective fishing laws were changed in 1968, many Portuguese boats stopped their activity in Newfoundland. In the early 1990s, the Canadian cod banks collapsed due to overfishing, and much of the Portuguese cod fleet was terminated. Only a few cod fishing boats remain nowadays; most bacalhau is imported from Norway and Iceland.

Bacalhau, the faithful friend, gained importance not only on the Portuguese table but also in the country’s culture. For instance, the expression dar um bacalhau (“to give a salt cod”) means to give a handshake. There’s even a street in the Lisbon neighborhood of Baixa called Rua dos Bacalhoeiros, but nowadays you won’t find a salt cod shop there.

When Lisboetas want bacalhau today, they head to Rua do Arsenal, where the grocery shop Pérola do Arsenal has stood, selling salted cod, for almost 90 years. Surrounded by tinned fish, spices and bacalhau in all sizes, senhor Rui is the master of cod. He proudly shows off the cheeks, the samos (swimming bladder) and the tongues – all beloved local specialties. In the days leading up to Christmas, he also stocks a special yellow-cured (cura amarela) cod, which comes from Iceland and costs €25 per kilo. Although the Portuguese traditionally prefer cod that has been cured in salt for 4 or 6 months, as well as cod cheeks, a succulent and delicious part of the fish, for Christmas Eve.

Like Pérola do Arsenal, the aforementioned Manteigaria Silva, founded in 1890, is sadly one of the few shops to have survived gentrification in the Baixa district. José, similar to senhor Rui, likes to explain why he loves to eat the cheeks by hand (“impossible to use a fork”) or why the tongues (which are actually the lower part of the fish’s neck) are so good and have no bones. While salt cod requires soaking in water for two to three days (as opposed to frozen cod, which doesn’t need to be rehydrated), that hasn’t deterred true bacalhau lovers from buying this traditional product. Besides cod, Manteigaria Silva is still a must for cheese, porco preto (Iberian ham from Alentejo) and charcuterie, especially the ones cured on site.

While salt cod is a traditional Christmas Eve meal, it can be found in Lisbon year-round. There are restaurants like A Casa do Bacalhau that specialize in it, but most tascas and restaurants in the city serve bacalhau in some form. The fish is even getting the museum treatment: City Hall and the Lisbon Tourism Board recently teamed up to open Centro Interpretativo da História do Bacalhau, an interactive museum in central Praça do Comércio with a dedicated restaurant and shop. With such a deep history, we imagine there’s a quite lot to say about Portugal’s national dish.

August 20, 2020 Building Blocks

August 20, 2020 Building Blocks

Sold by roving vendors, street carts and bakeries, spread with a triangle of soft cheese […] Posted in Istanbul April 25, 2017 Hold the Broth

April 25, 2017 Hold the Broth

We’ve been fascinated by dry pot (ma la xiang guo) since discovering it in Flushing last […] Posted in Queens December 28, 2012 Best Bites of 2012: Istanbul

December 28, 2012 Best Bites of 2012: Istanbul

Update: Kantin, Serger, Café Niko are sadly no longer open.

After four years of […] Posted in Istanbul

Published on December 11, 2020

Related stories

August 20, 2020

IstanbulSold by roving vendors, street carts and bakeries, spread with a triangle of soft cheese or tossed to circling seagulls from the ferry, the humble simit has become a quintessential symbol of Istanbul – and of Turkey more broadly. But there’s more to this sesame-coated bread ring that it may at first appear, as demonstrated…

Get a taste of the Queens that everyone is talking about; join our tour.

April 25, 2017

Queens | By Trevor Hagstrom

QueensWe’ve been fascinated by dry pot (ma la xiang guo) since discovering it in Flushing last year, probably a decade after it had risen to match the popularity of hot pot in Beijing. This streamlined hot pot is a wok stir-fry of all your favorite hot pot ingredients, served in a large, half-empty bowl, as…

December 28, 2012

IstanbulUpdate: Kantin, Serger, Café Niko are sadly no longer open. After four years of publishing weekly dispatches from Istanbul’s culinary backstreets (on IstanbulEats.com and now on this site as well), we are still regularly surprised by new discoveries, impressed by the staying power of old standards and shocked by how quickly so much can change.…