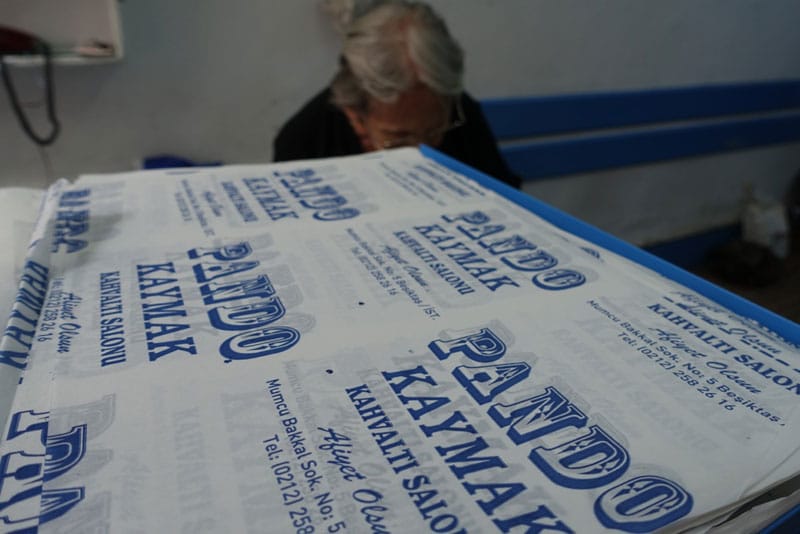

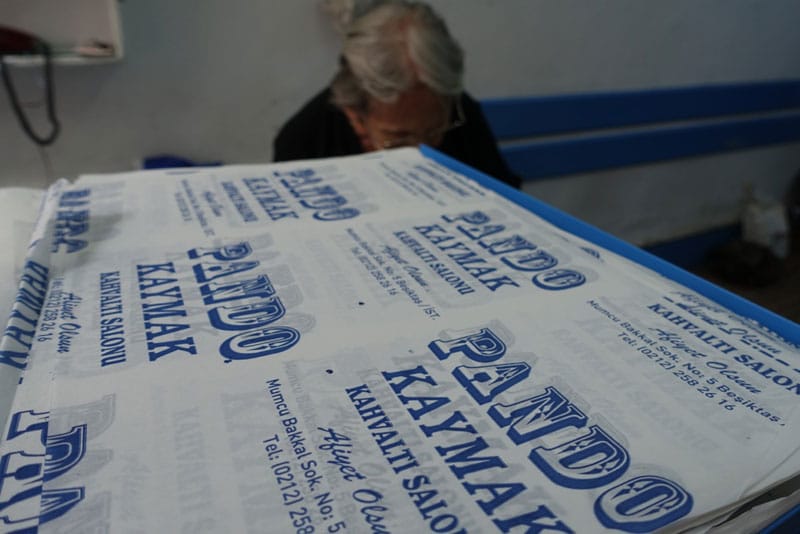

Last week we had our last meal at the iconic Beşiktaş kaymak shop Pando. The framed news clippings were all boxed up; the marble-topped tables that lined the blue and white walls of the tiny place were in the storage space of a friend somewhere in the neighborhood. All that was left was a space heater, soon to be taken away. Even still, Pando and his family were gathered there together, presumably with nowhere else to be. We sat out front at the last remaining table with Pando and his wife, Yuanna. Pando shuffled across the street through a swarm of people waiting in line outside of Karadeniz Pide ve Döner. He nodded to Asim Usta, who sent over a döner sandwich and a cup of ayran. Takeout, Pando’s last offering.

In his novella CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, George Saunders hilariously portrays an Orwellian vision of America in the not-so-distant-future, the country sick with violence and capitalism gone wrong, its infrastructure shattered. Set in a Civil War reenactment theme park, the story is totally absurd yet not so unrealistic.

Flipping through the pages of Turkish Airlines’ in-flight magazine, we always think of George Saunders when we settle on the advertisement for Bosphorus City, a luxury gated community out past the airport of Istanbul that is a recreation of the city itself. Some 10,000 people live on the shores of this manmade strait, sleeping in like-real Ottoman villas (if they have the means) or more true-to-life apartment towers boasting views of the water. Residents kayak past an Ottoman palace replica, stroll through an ersatz “Ortaköy Village” and ride bikes across suspension bridges connecting the two shores as a part of the heavily structured social life engineered by the Bosphorus City administration.

In the online virtual tours of Bosphorus City, there are no pictures of aunties sweeping their stoop in billowing pajamas, no underwear-clad teens sunning themselves on the waterfront sidewalk at Sarıyer, no one hawking stuffed mussels or waiting in a dolmuş line. No cats eating hot dogs left out for them. Not even a puff of grill smoke or a single empty water jug tied to a tree for you to slip your bottle cap into to help the poor and crippled. We imagine the 10,000 people who live in Bosphorus City describing their new home on one of the Seven Hills to relatives: “It’s just like Istanbul, but clean.”

Bosphorus City is an absurd example, but we wonder how the planners would fit Pando and his kaymak shop into the narrative of their development. We imagine they’d howl out loud at the suggestion.

But brace yourselves for it: With every closure of another small business, Istanbul (the actual city on the Bosphorus) inches closer to becoming Bosphorus City. There are the brutal shocks to the city like the full-scale evacuation of poor neighborhoods such as Sulukule and Tarlabaşı, but we barely notice the tiny incremental changes – another barbershop closes, an old man’s teahouse disappears, the sahlepçi doesn’t make his rounds as much anymore. We don’t cling to these antiquated businesses for the sake of nostalgia; we do so because they provide much-needed anchors for life in this city.

Pando’s eviction is not a crisis for the kaymak-obsessed. There are many great options within whiffing distance of his musty old shop. But the shop’s closure is another notification that the anchors which life in Istanbul depend upon are grounded in nothing but sand. Pando’s family business has hung on through a century of tremendous change that largely purged the city of older small businesses and its centuries-old esnaf, or tradesmen’s, culture. His family was perhaps the only one in Beşiktaş to keep the doors open no matter what. And through that unwillingness to be branded and go big or be banished, Pando offered generations a reminder that Istanbul at its best is a heavily lived-in place, the beauty living in its most worn spots.

The newly appointed Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu has unveiled a theme of “restoration” for his administration, vowing to right the wrongs of the past 90 years. But as shopping malls seem to fall from the sky and historic residential neighborhoods are colonized by hotels, the pair of evicted Ottoman-era artisans we are sitting with make us wonder if “preservation” might be a better place to start.

Published on September 09, 2014

Related stories

December 25, 2020

Porto | By Cláudia Brandão

PortoIn the three months of confinement in Porto, I had to learn to live very differently. The days stretched on, embedded with a fear of going out. Those of us whose jobs permitted it learned to work from home, to spend all our free time confined within four walls, to look at the sky – and…

March 2, 2021

LisbonA former industrial center, eastern Lisbon has gained a new vibrancy of late, with old factories and decrepit warehouses made over into art galleries, restaurants and breweries. Not even the pandemic has been able to stop this development: A Praça, a marketplace connecting Lisboetas with producers from around the country, has recently set up shop…

March 10, 2016

The Syrian Kitchen in ExileSince Syrians took to the streets in March 2011 to demand reform, news from Syria can be boiled down to montages of people angry, bloodied and afraid; bearded young men in military fatigues dodging behind crumbled buildings; the ominous black flags of the so-called Islamic State; children pulled from the rubble of bombed out buildings;…