Zeynep Arca Şallıel had a successful career in advertising in Istanbul, but in 1995 she decided to take on a daunting new challenge: taking part in the revival of small-scale viniculture in the ancient winemaking region of Thrace. “I wanted to do something with soil, something that mattered a little bit more,” she says. Her father had always dreamed of making wine, so together, they started Arcadia Vineyards. Their vineyards are planted on the 65 million-year-old eroded rock of Istranca Mountain, which creates a border between Turkey and Bulgaria. We drove two hours west from Istanbul through rolling hills of drying sunflower fields to learn how this pioneering winemaker is making great wines under difficult circumstances.

Arcadia made its first vintage in 2009, but the long road to that moment began in 2002, when the Turkish government legalized small-scale wine production. Previously, only companies producing more than 1 million liters of wine were allowed to exist. After the law changed, Şallıel immediately started working on Arcadia, and as a result, it is the first winery in the region since the founding of the modern Turkish republic. Şallıel spent two years crisscrossing the region, searching for the perfect land that would give her wine “a fresh, fine fruit terroir.” Although Şallıel was educating herself in viticulture, she knew she needed a world-class mentor. For a year, she chased down Dr. Michel Salgues, a noted French winemaker and viniculture advisor, until he finally agreed to help Şallıel start Arcadia.

Together, they chose the perfect 35-hectare piece of land, where they could plant the same varieties on different parcels, and each would have a different terroir. “This land was one of the most well-known viticulture regions until the 19th century,” explains Şallıel, who has a wild head of curly brown hair and a mischievous sparkle in her eye. “Our land is near the old şarap yolu” – wine route – “where the Ottomans exported 360 million liters of wine to France each year.” However, the Balkan Wars and World War I devastated the region, killing the wine producers and their vines. When Şallıel began to prepare the soil, she found remnants of those 100-year-old vines in her plot.

Together, they chose the perfect 35-hectare piece of land, where they could plant the same varieties on different parcels, and each would have a different terroir. “This land was one of the most well-known viticulture regions until the 19th century,” explains Şallıel, who has a wild head of curly brown hair and a mischievous sparkle in her eye. “Our land is near the old şarap yolu” – wine route – “where the Ottomans exported 360 million liters of wine to France each year.” However, the Balkan Wars and World War I devastated the region, killing the wine producers and their vines. When Şallıel began to prepare the soil, she found remnants of those 100-year-old vines in her plot.

Soil preparation took a year of hard work. For 60 years, the land was under conventional sunflower and wheat cultivation, which created an extremely hard clay layer. Şallıel brought in heavy-duty tractors to break the surface, but villagers suspected she was mining for gold, so they called the police. Luckily, the police believed her wine story and let her continue. Şallıel adjusted the soil acidity level, planted cover crops to fix nitrogen and inoculated the soil with beneficial bacteria. Finally, she planted cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, merlot, sauvignon blanc, sauvignon gris, sangiovese and pinot gris, as well as the more native öküzgözü and narince varietals. In 2009, Arcadia had its first harvest and won gold in international wine competitions. After hanging out with Şallıel for a day, we realized those awards were hard won and well deserved.

We tagged along to see the harvest, accompanied by her huge Kangal dog, Haydut (“Bandit”). On the way, Şallıel stopped to remove errant vines from new grafts, apologizing that she couldn’t help herself. Women from nearby Hamitabat village were carefully clipping heavy clusters of grapes and placing them into small plastic bins with aeration holes. This labor-intensive process ensures the grapes do not burst and oxidize, which would give the wine off-flavors. Next, workers truck the bins to the gravity-fed winery in the center of the property for a gentle pressing.

We took refuge from the midday sun in the lofty, cool winery, which is filled with huge stainless steel tanks. There we met Kadir Bora, an agriculture technician from Tekirdağ University, who is in charge of winemaking and has been with Arcadia for 10 years. He gave us a taste of the sauvignon gris juice pressed the day before, fresh from the tank. The syrupy yellow elixir tasted like fig, lemon and honeysuckle. Then Bora offered a glass of the newly fermented juice, which had passion fruit, banana, lemon and fig flavors. “We should have some with lunch,” suggested Şallıel. Bora gave Şallıel tastes of red wines at various stages of fermentation and the two discussed next steps.

We took refuge from the midday sun in the lofty, cool winery, which is filled with huge stainless steel tanks. There we met Kadir Bora, an agriculture technician from Tekirdağ University, who is in charge of winemaking and has been with Arcadia for 10 years. He gave us a taste of the sauvignon gris juice pressed the day before, fresh from the tank. The syrupy yellow elixir tasted like fig, lemon and honeysuckle. Then Bora offered a glass of the newly fermented juice, which had passion fruit, banana, lemon and fig flavors. “We should have some with lunch,” suggested Şallıel. Bora gave Şallıel tastes of red wines at various stages of fermentation and the two discussed next steps.

Although wine is surrounded by an air of mystery and expertise, Şallıel keeps it simple: grow delicious grapes, then try to keep their flavor in the final product. In order to grow grapes that express interesting terroir, Şallıel manages the vineyards sustainably. She and her team work to maintain a balanced environment through minimal spraying, allowing birds their share and keeping the original oak trees as permanent animal habitats. Grapes are carefully harvested, pressed and fermented; the wine is never pumped or sterilized. Reds are aged in French oak barrels, then bottled and hand-stacked in Arcadia’s underground cellars. “It costs three times as much to make wine this way,” Şallıel told us. We tasted the vineyard’s vitality in Arcadia’s 2011 A series blend: 80 percent cabernet sauvignon, 20 percent cabernet franc. “I taste licorice, balsamic, blackberry jam and leather,” Şallıel said. “It would go well with roast lamb from this region.” Every sip was exciting and didn’t tire our palates. We didn’t have any lamb, but enjoyed the wine just the same with the grape harvester’s carb-heavy lunch of beans, pasta and irmik helvası (semolina pudding).

This is Arcadia’s sixth harvest year and by far their most difficult one. Cold weather during fruit set and a super-wet summer caused downy and powdery mildew to destroy 50 percent of the grapes. When we visited during the sauvignon blanc harvest, Şallıel invited us to return for the red grape harvest at the end of September. However, a sudden 20-minute hailstorm came and destroyed what few red grapes were left. They salvaged what little they could and will use the grapes to make rosé. “What can we do? It would be too expensive to cover the whole vineyard to protect it from hail,” said Şallıel, who is resigned to buying grapes to produce red wine, a first for Arcadia. This year they will make only 60,000 bottles of wine instead of their usual 100,000.

In addition to the erratic, extreme weather, Şallıel is also dealing with a hostile alcohol policy environment in Turkey. While her fellow wine producers in Armenia proudly debut their wine from the top of Mount Ararat, Şallıel must create a website that is invisible to viewers in Turkey. New 2013 laws state that no alcohol companies may advertise; this means no pictures of Arcadia bottles on the Turkish website, no signs in wine stores explaining Thracian terroir, no free wine tastings at the vineyard, no donating wines as an event sponsor. “The Turkish wine market has shrunk about 25 percent since the new laws took effect,” said Şallıel. For a nascent brand from a re-emerging wine region, these laws are limiting and intimidating. Only two other producers are making wine in neighboring villages, and it is nearly impossible to get an alcohol license for vineyard tastings now. “In many countries, wine is treated as a complement to food, and it is not subject to the same laws as hard alcohol,” says Şallıel. “There is a big economical opportunity for this country, for Turkish wine abroad and for tourism. We just need a change in policy.”

She is hopeful still and believes in the future of the Thracian wine region. Last year she worked with Thracian producers and the region’s tourism board to create the Thrace Wine Route (Vineyard Route for Turkish audiences, for legal reasons). Şallıel thinks producers have a fighting chance if they work together to promote the region as a whole instead of just their individual wineries. “Many people go to Greece and Bulgaria for wine, but they never cross the border because they don’t know about us,” said Şallıel, “If they came, they wouldn’t know where to go – even Turkish people don’t know where to go!”

She is hopeful still and believes in the future of the Thracian wine region. Last year she worked with Thracian producers and the region’s tourism board to create the Thrace Wine Route (Vineyard Route for Turkish audiences, for legal reasons). Şallıel thinks producers have a fighting chance if they work together to promote the region as a whole instead of just their individual wineries. “Many people go to Greece and Bulgaria for wine, but they never cross the border because they don’t know about us,” said Şallıel, “If they came, they wouldn’t know where to go – even Turkish people don’t know where to go!”

Şallıel has heavily invested in her land; an 18-room hotel, spa and restaurant is under construction. Pear orchards, a vegetable garden and truffle-inoculated oak trees intermingle with the vineyards and wild lands. Gradually, her 200-hectare plot is living up to its ancient name, Arcadia, which means “paradise on earth.” As we left for Istanbul, the always-grounded Şallıel brought us back from our lofty Dionysian visions: “It is a fascinating job if you love it. If not, it is probably a pain in the ass.”

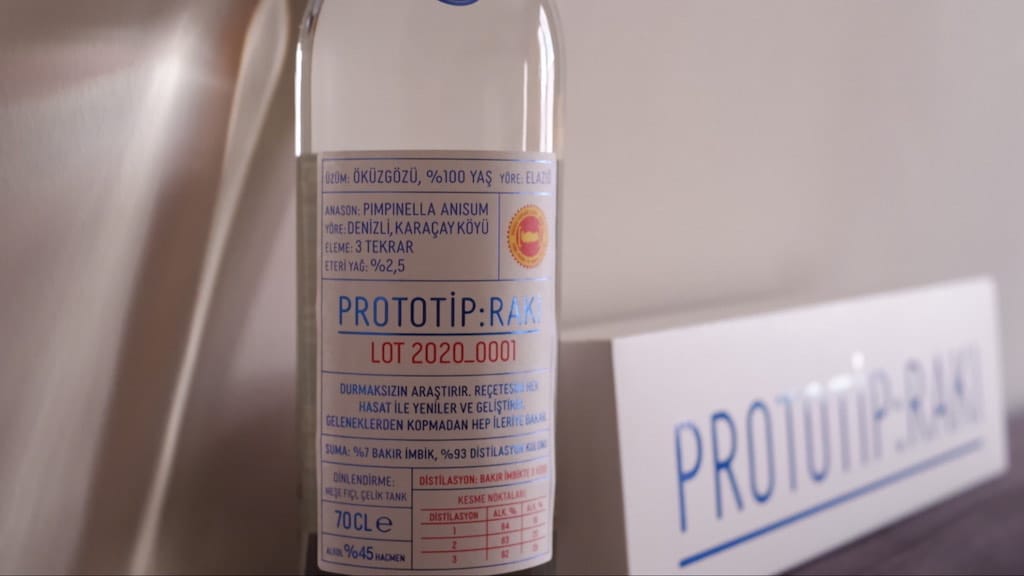

November 29, 2021 Prototip Rakı

November 29, 2021 Prototip Rakı

It's nearing the end of 2021 and Turkey is bracing stormy weather. The economy […] Posted in Istanbul March 24, 2014 Tres Leches

March 24, 2014 Tres Leches

Pastel de tres leches is beloved throughout much of Latin America, and yet its origins […] Posted in Mexico City September 4, 2014 Gastronomika

September 4, 2014 Gastronomika

Update: Gastronomika’s community kitchen is not at SALT Beyoğlu anymore.

Who says […] Posted in Istanbul

Published on November 25, 2014

Related stories

November 29, 2021

Istanbul It's nearing the end of 2021 and Turkey is bracing stormy weather. The economy is struggling, the Turkish lira has lost a quarter of its value this year, rental prices are soaring nationwide and purchasing power has been compromised. On top of it all, already sky-high taxes on alcohol were hiked again earlier this…

March 24, 2014

Mexico CityPastel de tres leches is beloved throughout much of Latin America, and yet its origins remain a mystery. Some people claim that it was first baked in Nicaragua, others that the recipe was first printed on the label of a well-known brand of canned condensed milk in Mexico. Tres leches is usually a sponge cake soaked…

September 4, 2014

IstanbulUpdate: Gastronomika’s community kitchen is not at SALT Beyoğlu anymore. Who says there’s no such thing as a free lunch? In fact, over at Gastronomika, a new Istanbul culinary project, the food is served not only free of charge but also with an intriguing – and ambitious – backstory. As Gastronomika’s founders describe it, the…