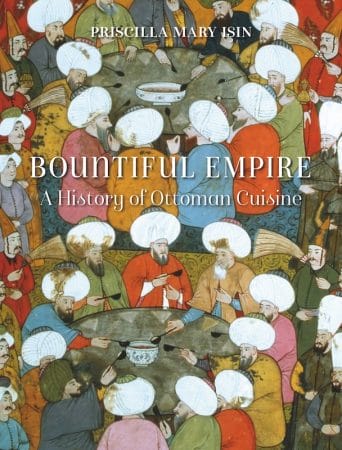

We recently spoke to food historian and researcher Priscilla Mary Işın about her new book, Bountiful Empire: A History of Ottoman Cuisine (Reaktion Books; May 2018). She has previously published edited transcriptions of texts relating to Ottoman food culture and Sherbet and Spice: The Complete Story of Turkish Sweets and Desserts (2008), a social history of Ottoman sweets and puddings.

How did you first become interested in food history, particularly in the Ottoman world?

How did you first become interested in food history, particularly in the Ottoman world?

I moved to Ankara in 1973 immediately after graduating from university in the UK. My husband and I lived in the same block of flats as my lovely in-laws and often ate meals with them and other relatives. The delicious food, particularly vegetable dishes, was one of the aspects of life in Turkey that amazed me most, especially being British! Up to then my experience of vegetables had been limited to boiled vegetables with meat, cauliflower cheese and coleslaw. I started collecting Turkish recipes, mostly from my mother-in-law and my husband’s maternal uncle Cevat, who was a merchant sea captain and superb cook.

I decided to compile a book of Turkish vegetable recipes and publish it in England to introduce British cooks to the joys of vegetable cookery, with an introduction explaining the history of Turkish cuisine, which I knew nothing about. No one I knew in Ankara could help me but after moving to Istanbul in 1980 I began to meet people who did. This was just the time when Turkish food culture and history were beginning to be taken seriously by academics and researchers.

A symposium on Turkish cuisine was held in 1981, followed by a symposium on traditional Turkish confectionery in 1983. Around that time I met Prof. Dr. Günay Kut, an expert on Ottoman literature and one of the first academic researchers into Ottoman cuisine, who told me about sources like Prof. Dr. Süheyl Ünver’s book on the Cuisine of Sultan Mehmed II (1952) and his transcription of an 18th-century manuscript cookery manual (1948) and that there were 19th-century recipe books printed in Ottoman Turkish. Over the next few years I visited every second-hand bookshop I could find in Istanbul in search of them. The only trouble was I couldn’t read them. Around the mid-1990s Prof. Turan Yazgan persuaded me to learn Ottoman Turkish script and I eventually learned to read the recipes, which are in fairly straightforward Turkish. I practiced on a cookery book called Aşçıbaşı by Mahmud Nedim, and with help from several people over difficult words and passages.

A symposium on Turkish cuisine was held in 1981, followed by a symposium on traditional Turkish confectionery in 1983. Around that time I met Prof. Dr. Günay Kut, an expert on Ottoman literature and one of the first academic researchers into Ottoman cuisine, who told me about sources like Prof. Dr. Süheyl Ünver’s book on the Cuisine of Sultan Mehmed II (1952) and his transcription of an 18th-century manuscript cookery manual (1948) and that there were 19th-century recipe books printed in Ottoman Turkish. Over the next few years I visited every second-hand bookshop I could find in Istanbul in search of them. The only trouble was I couldn’t read them. Around the mid-1990s Prof. Turan Yazgan persuaded me to learn Ottoman Turkish script and I eventually learned to read the recipes, which are in fairly straightforward Turkish. I practiced on a cookery book called Aşçıbaşı by Mahmud Nedim, and with help from several people over difficult words and passages.

Discovering Turkish translations of accounts of travels in the Ottoman Empire by people like La Baronne Durand de Fontmagne, Nicolas de Nicolay and Ignatius Mouradgea de Ohsson expanded my knowledge of Ottoman food history. It turned out that for centuries foreigners had been fascinated by everything about the Ottomans, including what they ate. And in Turkish sources food culture turned out to be everywhere – in Ottoman period poetry, history, court records, travel accounts, probate inventories, diaries, novels, accounts registers, songs, cartoons and dictionaries. To cut a long story short, I found myself on the shore of an amazing, boundless and little known ocean of Ottoman cuisine – which I’ve been exploring in its many aspects ever since.

The book spans a large swath of time – the entirety of the Ottoman Empire as well as the political entities that preceded it – and makes use of a wide range of sources, from official state documents to travelogues, and even paintings and objects. Can you tell us more about the research process for the book?

Writing a bird’s eye view of any big subject is a challenge. Over the last 35 years spent researching I have accumulated tens of thousands of pages of notes about Ottoman culinary culture and its roots, and it is hard not to drown in detail. That’s why I wrote the first two [overview] chapters last, after finishing the others. In the course of working on the chapters devoted to specific aspects like cooks and hospitality an overall picture gradually crystallized. Also I had just written a book in Turkish on the history of major culinary traditions, including Iran, India, the Ancient Greeks, Seljuks, Byzantines, Ottomans and Europe. Studying these gave me fresh insights into Ottoman foodways, because as well as differences it revealed links and parallels between them.

Were there any sources that you found to be particularly illuminating about Ottoman cuisine? Tangentially, were their any sources that surprised you with their usefulness?

Often a single line is illuminating. A good example is a line in a poem by the 15th-century poet Kaygusuz Abdal, who wrote “Two hundred trays of baklava, some with almonds, some with lentils.” This is not only the earliest written record of the word baklava, but tells us that baklava was a feast dish (as the two hundred trays implies), and that there was a time when lentils were used as a filling. For a long time I was doubtful about the lentils, but when I mentioned it to the food historian Charles Perry he confirmed that baklava with a lentil filling indeed existed and sent me an early 16th-century Persian recipe for “baklava of Karaman” filled with lentil purée. This is even more amazing because Karaman was the region of southern Turkey where Kaygusuz Abdal himself came from.

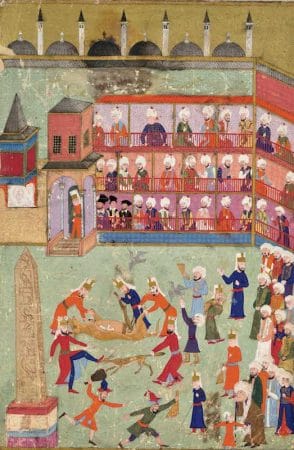

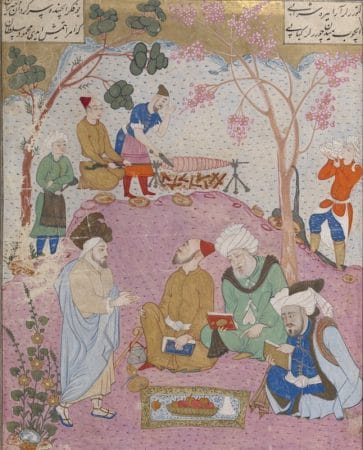

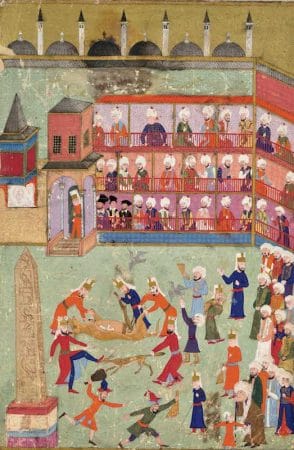

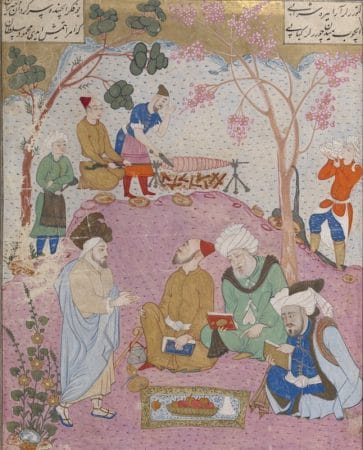

Some pictures have also thrown light on an unknown area. Two miniature paintings illustrating döner kebab in picnic scenes dating from 1616 that I came across in 2014 reveal that döner kebab was known in Istanbul at that period, although there is no mention of it in any Ottoman written sources. Along the same lines, a series of cartoons in Karagöz magazine published during the late Ottoman period illustrate aspects of food culture not found in any engravings or miniature paintings.

Some pictures have also thrown light on an unknown area. Two miniature paintings illustrating döner kebab in picnic scenes dating from 1616 that I came across in 2014 reveal that döner kebab was known in Istanbul at that period, although there is no mention of it in any Ottoman written sources. Along the same lines, a series of cartoons in Karagöz magazine published during the late Ottoman period illustrate aspects of food culture not found in any engravings or miniature paintings.

You take a comprehensive approach to cuisine in that various aspects of food culture are addressed, such as hospitality and charity, food laws and trade, and etiquette. Why did you decide to look through such a wide lens?

I am particularly interested in the way food reflects Ottoman society and the way people of different classes and occupations lived. Foods and food-related customs are a way of bringing that lost world to life in my mind and I hope in the minds of my readers. Food was integral to every aspect of Ottoman life, even politics. As well as more obvious universal phenomena like official banquets, presenting gifts of sweetmeats and fruit in particular was a part of state protocol. Statesmen and other officials sent such gifts to express goodwill, congratulations, condolences and welcome. I came across interesting examples of food gifts in thank-you letters written by the mother of Sultan Abdülaziz to people who, in hope of royal favors, had sent her foods that included even yogurt and pickles!

The term ‘Ottoman cuisine’ usually refers to palace cuisine or, at the very least, focuses almost exclusively on food in Istanbul, the capital. Was it important for you to look more broadly at the food eaten across the empire? Does this regional variety make it difficult to discuss ‘Ottoman cuisine’?

The heavy bias towards Istanbul and the palace in surviving historical sources and modern writing on Ottoman cuisine is something I have done my best to redress in the book. Ironically, many foods and dishes that have long since been forgotten in Istanbul still survive in other Turkish provinces today. That has motivated me to travel as widely as possible in Turkey over the last decade. In April this year I visited a village in Afyonkarahisar where a lady still makes karın yağ, which is clarified sheep’s butter stuffed into a dried sheep’s stomach. This is a very ancient Turkish food, recorded in the pre-Ottoman period and eaten at the Ottoman palace. It was amazing to taste this delicious butter for myself.

I give examples of distinctive foodways of Ottoman Christians and Jews, and particular regional features, such as foxtail lily leaves used in Eastern Anatolia and maize in the Black Sea region. At the same time there are many dishes and foodways that illustrate how a typical Ottoman character came to stamp cuisines throughout the empire. The Austrian Iranologist Bert Fragner calls this phenomenon the “Ottoman culinary empire.” This came about for several reasons, such as the posting of state officials to provincial towns and cities, where they introduced typical Istanbul dishes but also discovered local specialties that were then incorporated into mainstream cuisine; and the provision of standard Ottoman dishes at the network of charity kitchens established around the empire, a topic widely discussed by Prof. Amy Singer.

I give examples of distinctive foodways of Ottoman Christians and Jews, and particular regional features, such as foxtail lily leaves used in Eastern Anatolia and maize in the Black Sea region. At the same time there are many dishes and foodways that illustrate how a typical Ottoman character came to stamp cuisines throughout the empire. The Austrian Iranologist Bert Fragner calls this phenomenon the “Ottoman culinary empire.” This came about for several reasons, such as the posting of state officials to provincial towns and cities, where they introduced typical Istanbul dishes but also discovered local specialties that were then incorporated into mainstream cuisine; and the provision of standard Ottoman dishes at the network of charity kitchens established around the empire, a topic widely discussed by Prof. Amy Singer.

We started out as a food blog focused on street food and simple family-run restaurants in Istanbul. How common were street food vendors and small canteens in Ottoman times?

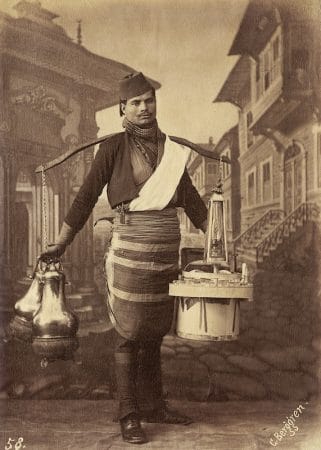

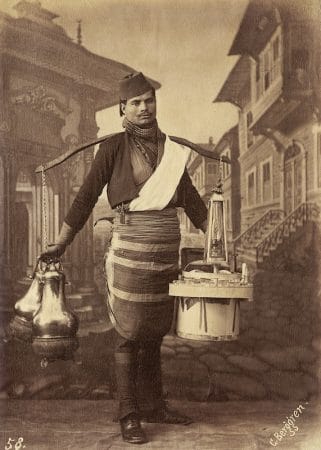

Street food vendors were very common in towns and cities, selling a wide range of prepared foods and beverages. Simit, muhallebi, salep and sherbet are just a few examples. In commercial neighborhoods there were small restaurants specializing in one or a few types of dishes, kebab, tripe soup and börek being the most common. In Istanbul the diversity of food sold in the streets was astonishing, as attested by Evliya Çelebi’s 17th-century account of Istanbul’s tradesmen in his Book of Travels.

You mention in the book that a lot of restaurants claiming to offer Ottoman cuisine rarely do so in reality. If our readers want to get a taste of Ottoman dishes in Istanbul, what and/or where should they eat?

Modest local restaurants, such as the esnaf lokantası type, pidecis and börekçis, especially in provincial towns, are usually the best places to taste truly traditional dishes that haven’t changed much since Ottoman times. In my limited experience fancy restaurants alter even Ottoman inspired dishes so radically that they give no idea of what the originals might have tasted like.

I like kebab houses of the type known as ocak başı, where the cooking is done over charcoal and lamb is used instead of beef; tripe soup at a good işkembeci, where they also sell sheep’s head (I wasn’t too keen when my husband first took me to eat this in Ankara in the 1970s, but I found it was delicious, the meat served removed from the bones, flavored with plenty of oregano). You can try traditional milk puddings of several kinds at a muhallebici like Saray in Eminönü, and during the winter months in Istanbul try boza – a thick tangy, sweet millet beer sprinkled with cinnamon and roasted chickpeas. The best pide I ever ate was cheese-topped pide in Trabzon, where the döner kebab with pilaf was also fantastic. There are hundreds of other good ones – just go at lunchtime and make sure the customers are mainly local office and shop workers. The ancient dish büryan (roasted sheep or goat) roasted in a tandır (pottery pit oven) is something to look out for in provincial cities like Bitlis, where I first tasted it, and I have been told a good place to eat it in Istanbul is at a restaurant in Siirt Pazarı on Saturday mornings.

You can purchase “Bountiful Empire: A History of Ottoman Cuisine” directly from Reaktion Books.

October 6, 2017 CB Book Club

October 6, 2017 CB Book Club

Photographer David Hagerman is one half of the duo behind the new cookbook Istanbul […] Posted in Istanbul May 3, 2019 CB Book Club

May 3, 2019 CB Book Club

Chef, food writer, and MasterChef champion Tim Anderson shares his love of Tokyo and […] Posted in Tokyo September 15, 2016 CB Book Club

September 15, 2016 CB Book Club

We recently spoke with travel writer Caroline Eden and food writer Eleanor Ford about […] Posted in Tbilisi

Published on July 23, 2018

Related stories

October 6, 2017

Istanbul | By Culinary Backstreets

IstanbulPhotographer David Hagerman is one half of the duo behind the new cookbook Istanbul & Beyond: Exploring the Diverse Cuisines of Turkey, which will be published by Rux Martin Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (USA) on October 10. Together with Robyn Eckhardt, his journalist wife and the author of Istanbul & Beyond, he has crisscrossed Turkey countless…

May 3, 2019

Tokyo | By Culinary Backstreets

TokyoChef, food writer, and MasterChef champion Tim Anderson shares his love of Tokyo and Japanese food culture in his new book, Tokyo Stories: A Japanese Cookbook (Hardie Grant, 2019). After moving to London, Anderson, who is originally from Wisconsin, won MasterChef in 2011, a title that catapulted him into a position as one of the…

September 15, 2016

Tbilisi | By Culinary Backstreets

TbilisiWe recently spoke with travel writer Caroline Eden and food writer Eleanor Ford about their new cookbook, Samarkand: Recipes & Stories from Central Asia & the Caucasus (Kyle Books; July 2016). Eden has written for the Guardian, the Telegraph and the Financial Times, among other publications, while Ford has been an editor for the Good…