Nuno Mendes is excited. He’s standing at my kitchen counter, where laid out before him are pieces of half-moon-shaped dough, each encasing a juicy meat mixture. They’re about to go into a pan filled with bubbling oil. My mom, Lica, is nervous. She is sharing her mother’s recipe for pastéis de massa tenra, a traditional Portuguese savory pastry, with the highly esteemed chef of Chiltern Firehouse and Taberna do Mercado in London. He has heard about her mouth-watering pastéis from a mutual friend and decided to see for himself just how good they are.

Worried that the dough isn’t quite right, she drops in the first one and the pastry bubbles up crispy, as it should. When it’s finished, she gives it to Mendes, who takes one bite and says, “Wow, these are amazing!” My mom is relieved, and Mendes is delighted because he did this very same thing as a kid with his grandmother: preparing the dough, carefully kneading it and then spinning it a bit in his hands, before rolling it out, cutting it and filling it with the meat mixture.

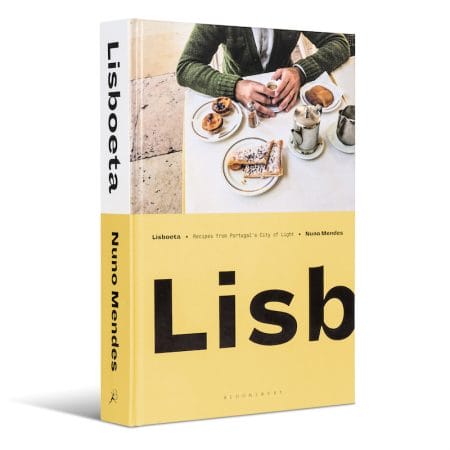

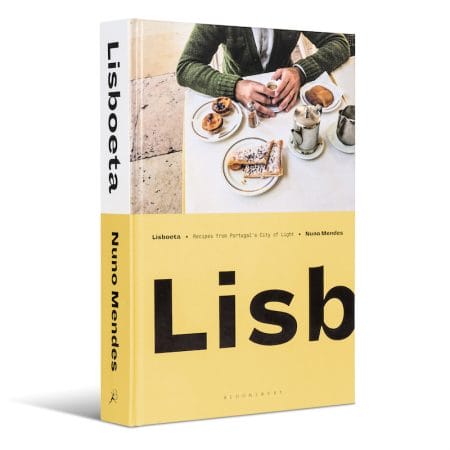

The recipe is one of the many Portuguese dishes that Mendes honors in Lisboeta: Recipes from Portugal’s City of Lights, his new book published by Bloomsbury UK. With its brilliant writing and amazing photographs, the book is a love letter to Lisbon, the “city of light,” where he was born and lived until he was 19. The young Mendes left Portugal with aspirations to become a marine biologist initially, traveling to the U.S. for his studies. But he was soon seduced by food and set his mind to becoming a culinary wizard, eventually settling in London where he first began The Loft Project, a temporary supper club held in his home in East London, and then opened Viajante, a restaurant that was awarded a Michelin star.

The recipe is one of the many Portuguese dishes that Mendes honors in Lisboeta: Recipes from Portugal’s City of Lights, his new book published by Bloomsbury UK. With its brilliant writing and amazing photographs, the book is a love letter to Lisbon, the “city of light,” where he was born and lived until he was 19. The young Mendes left Portugal with aspirations to become a marine biologist initially, traveling to the U.S. for his studies. But he was soon seduced by food and set his mind to becoming a culinary wizard, eventually settling in London where he first began The Loft Project, a temporary supper club held in his home in East London, and then opened Viajante, a restaurant that was awarded a Michelin star.

As he writes in the book: “Ironically enough it took leaving home and traveling elsewhere for me to realize that the Portuguese table is one of the best in the world.” So he set out to create an English-language book that celebrates iconic Portuguese dishes, such as custard tarts, pão-de-ló (sponge cake), rice with turnip greens and the oozy, gorgeous prawn turnovers that started this whole adventure. Intertwined with these recipes are six Lisbon food stories on subjects ranging from our beloved tascas to the annual Santo António festival. Below is a condensed version of a recent interview with Mendes, who was on a visit to Portugal to promote his new book.

Did living outside of Portugal for so many years give you a different perspective on Portuguese cuisine? How did that influence your approach to the book?

Rather than focus on the many modern restaurants in Lisbon, I wanted to concentrate on my childhood memories and on the everyday food people have been eating in Lisbon for years. I wanted to represent the memories, the building blocks that have helped the cuisine to develop into what it is today, though sometimes I wonder if it’s going in the right direction… Luckily there are still some great old places. The other day I went with a friend to Colina, a restaurant I used to go to with my father, around 30 years ago. It still has the classic things I like to eat here, like cuttlefish or rissóis, simple things.

When you came to Portugal to research the book, did you find many surprises?

When you came to Portugal to research the book, did you find many surprises?

There are more people than I imagined who are trying to rescue old ideas and recipes. I think there’s a lot of innovation, which is needed. But on the other hand there are people who are proud of their heritage and are trying to preserve traditional Portuguese gastronomy, something that for a long time was forgotten – this made me very happy. I met people working to maintain and honor the produce and the culinary traditions, who are respecting small producers. So many great ingredients and products that we didn’t properly cherish are coming back thanks to people like Catarina Portas [owner of the design shop A Vida Portuguesa]. It seems that international recognition was needed for us to start loving all of these traditional things. But at least it happened, which is fun to see.

Your book will raise the international profile of Lisbon’s food. Do you see it as more than just a recipe book?

The book is a bit of a love letter to Lisbon. I wanted to include both the city’s food and its stories to show people the Portuguese reality, the diversity and the culture that Lisbon has and represents. It’s more than a recipe book. There are so many stories and memories included. Even with the increase in tourism, people are still only just discovering the city, and there’s still a lot of work to be done [to raise its profile].

Also we’re always trying to innovate, but sometimes it’s also good to perfect what we have and adjust a bit, focus on the quality of the produce and make traditional dishes without so many variations as we sometimes see.

Another interesting aspect of the book is the way you discuss the post-colonial influence.

When I traveled across many of Portugal’s former colonies, I started to notice the impact we had, both the good and the bad. And sometimes we forget that in Lisbon. That’s why I tried to make more connections with the Lusophere [Portuguese speaking countries], because I think we should celebrate that instead of forgetting or hiding it.

Clarise, my partner, is South African and her father’s father was Portuguese – there’s a strong Portuguese presence in South Africa. Some years ago, we were at home and she picked up a cookbook and said she wanted to make prawn turnovers. Clarise showed me the recipe and I said, oh these are rissóis de camarão, and all of a sudden I had a flashback of being in my grandmother’s kitchen watching her make rissóis, probably one of my favorite salgados [savory fried snacks] in Portugal, and I remembered how much I love rissóis. Clarise and I made them together, they are so peculiar, the soft dough, the nice creamy filling inside. I was so happy with the flavor – it’s quite unique with the crispy outside. And I felt I needed to show this. All of a sudden I thought about the many rissóis de camarão I’ve eaten and how sad they often look in the display cases – they stay there all day cold, mushy, they don’t get crispy or have that burst of flavor. That experience with Clarise made think, if we show this to people and we serve them in the right way, people will like this.

Clarise, my partner, is South African and her father’s father was Portuguese – there’s a strong Portuguese presence in South Africa. Some years ago, we were at home and she picked up a cookbook and said she wanted to make prawn turnovers. Clarise showed me the recipe and I said, oh these are rissóis de camarão, and all of a sudden I had a flashback of being in my grandmother’s kitchen watching her make rissóis, probably one of my favorite salgados [savory fried snacks] in Portugal, and I remembered how much I love rissóis. Clarise and I made them together, they are so peculiar, the soft dough, the nice creamy filling inside. I was so happy with the flavor – it’s quite unique with the crispy outside. And I felt I needed to show this. All of a sudden I thought about the many rissóis de camarão I’ve eaten and how sad they often look in the display cases – they stay there all day cold, mushy, they don’t get crispy or have that burst of flavor. That experience with Clarise made think, if we show this to people and we serve them in the right way, people will like this.

The same with pastéis de nata [custard tart] – perhaps the most famous Portuguese export. They’re everywhere, but usually they are baked hours in advance and then sit in the pastry shop all day. When they’re cold, they’re not creamy anymore and the quality of the pastry suffers. I thought if I do this right, if I serve it at the right time, people would love them. That’s what ultimately led me to open Taberna do Mercado in 2015.

How would you describe your work at Taberna? You have a different take on Portuguese cuisine, a distinguished voice that you use in the book as well.

The restaurant reflects how I like to entertain. But it also reflects tradition. In Taberna, I made no more excuses for myself. I felt that all these years I’ve been working I never really did what I should have done for my country. All these amazing techniques that we have like açorda [a dish composed of soft bread with garlic and olive oil], cabidela [chicken rice cooked with blood and vinegar], the way we cook our rice… no one really knew about these things. There’s so much uniqueness to the cuisine, I mean massa de pimentão [red pepper paste], the way we use vinha d’alhos [garlic and wine marinade], cilantro, the many influences from the former colonies, it’s all fascinating. In London I think the chefs here were afraid of calling themselves Portuguese, so they said they were Iberian, they were focusing on Spain, almost like they were hiding the fact that they were Portuguese, afraid that Portuguese food wouldn’t sell. I mean it’s understandable; Portugal didn’t have a lot of projection as a food culture outside of the country. I want to break through that because we’re so unique and so different from Spain. I started to focus on dishes like rissóis, pézinhos de coentrada [pig trotters with cilantro], dishes that you really don’t see in Spain. The book is the same. I thought we needed to create awareness about our unique cuisine. I published the book in English even though I could have done it in Portuguese because I wanted it to be visible to an outside audience. I wanted people to read the book and be tempted to visit Lisbon and Portugal. This was my goal, really.

I noticed that many of your recipes have a strong Alentejo influence.

I grew up in Lisbon, but my family had a farm in Alentejo – my grandmother and my father had deep roots in the region – and I used to go to there all the time. The food that we ate was very much inspired by that region, and in the summer holidays I used to go there a lot and watch my grandmother cook. There’s amazing cuisine in other regions of Portugal, of course, but I love the fragrances of Alentejo – I love cilantro and garlic, olive oil, lemon, bread.

Which recipes do you think will get the most attention?

A lot of our guests at Taberna are very excited to try pão-de-ló. I also think the pastéis de nata are something that people are going to try at home. Rissóis are a little more labor intensive, so it’s hard to say if they’ll be popular. All these recipes are really personal to me, I love them all and they are close to my heart. For me, they all tell a story and are incredibly valuable. We wanted the book to be easy to work with. Some recipes require more time, others less time but they’re good to do at home. I mean the food culture in Portugal, the idea of having all the family in the kitchen, this book is full of that and hopefully draws you into it. I wanted to keep the recipes close to tradition. I wanted to connect readers with the food that can still be eaten and found in Lisbon. Like your mother’s amazing recipe for pastéis de massa tenra.

Recipe: Prawn and Shellfish Rice

Recipe: Prawn and Shellfish Rice

Arroz de marisco

Serves 4

5 tablespoons olive oil

2 banana shallots, diced

1 small onion, diced

1 small fennel bulb, trimmed and finely chopped

A bunch of coriander, leaves and stalks finely chopped

2 garlic cloves, crushed

Finely grated zest of 1 lemon

1/2 long red chilli, finely chopped

4 ripe plum tomatoes, coarsely grated

200g short-grain white rice, preferably Portuguese carolino, Japanese sushi or Spanish bomba rice, rinsed according to the packet instructions

600ml fish stock or water

40ml white wine

20 mussels, cleaned

20 clams, cleaned

16 large king or tiger jumbo prawns, shelled and deveined

A squeeze of lemon juice

Extra-virgin olive oil, to serve

Piri piri oil, to serve

Smoked paprika, to taste

Sea salt flakes and ground white pepper

In the greatest versions of arroz de marisco, rice is cooked in a stock made from the shells and trimmings of as many as ten different types of shellfish, and then the tender morsels of seafood are added at the end. Typically, tomatoes, onions and coriander are the other elements that make up this fantastic recipe, and the flavors come together perfectly. It’s a great dish to put in the middle of the table and let everyone dig in. If you’d like it less spicy, deseed the chilli.

Heat the olive oil in a pan over a medium heat. Add the shallots, onion and fennel and cook gently for 10 minutes, or until soft. Season with salt, pepper and paprika. Add the coriander stalks, garlic, lemon zest and chilli and cook for a few minutes, or until fragrant. Stir in the tomatoes. Increase the heat to caramelize the tomatoes a little, for extra flavor. Add the rice and cook for a few minutes to toast it. Add the fish stock or water and bring to the boil. Reduce the heat and simmer gently until almost cooked, about 15–20 minutes.

A few minutes before the rice is ready, add the white wine and tip in the mussels and clams. Cover with a lid and shake a few times. Cook for 3-4 minutes, then remove the pan from the heat. Discard any unopened shells.

Taste the rice for seasoning, keeping in mind that the mussels and clams will add extra salt. Add the prawns to the rice and cook for a few minutes until they turn pink. Stir in a squeeze of lemon juice, a little extra-virgin olive oil and the coriander leaves. Serve in shallow bowls, and don’t forget the piri piri oil!

Extract taken from “Lisboeta: Recipes from Portugal’s City of Light” by Nuno Mendes (Bloomsbury, £26), which is out now.

Published on December 27, 2017

Related stories

March 4, 2019

ShanghaiLegend has it that huangjiu, or yellow wine, was invented by Du Kang, the god of Chinese alcohol. Because huangjiu is fermented, the Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) benefits of the drink are legion, and include “invigorating the blood.” You can see for yourself if that’s the case on our Night Eats tour in Shanghai.

May 25, 2017

OaxacaEditor's Note: This spot is sadly no longer open. Oaxaca, consistently ranked as one of the three poorest of Mexico’s 31 states, can also claim the title of having the country’s worst school system. Demonstrations and rallies by students, teachers and unions are a regular occurrence in Oaxaca City, causing frequent gridlock in the center…

July 17, 2014

AthensEditor's note: We're sorry to report that Kelly's Cookbookstore has closed. Thinking we’d find something like New York City’s Kitchen Arts and Letters or London’s Books for Cooks, we paid a visit to Kelly’s Cookbookstore near Omonia Square. Like them, the shop is warm and inviting, its owners encyclopedic sources on all matters culinary. Unlike…